Welcome to the dark side of crypto’s permissionless dream

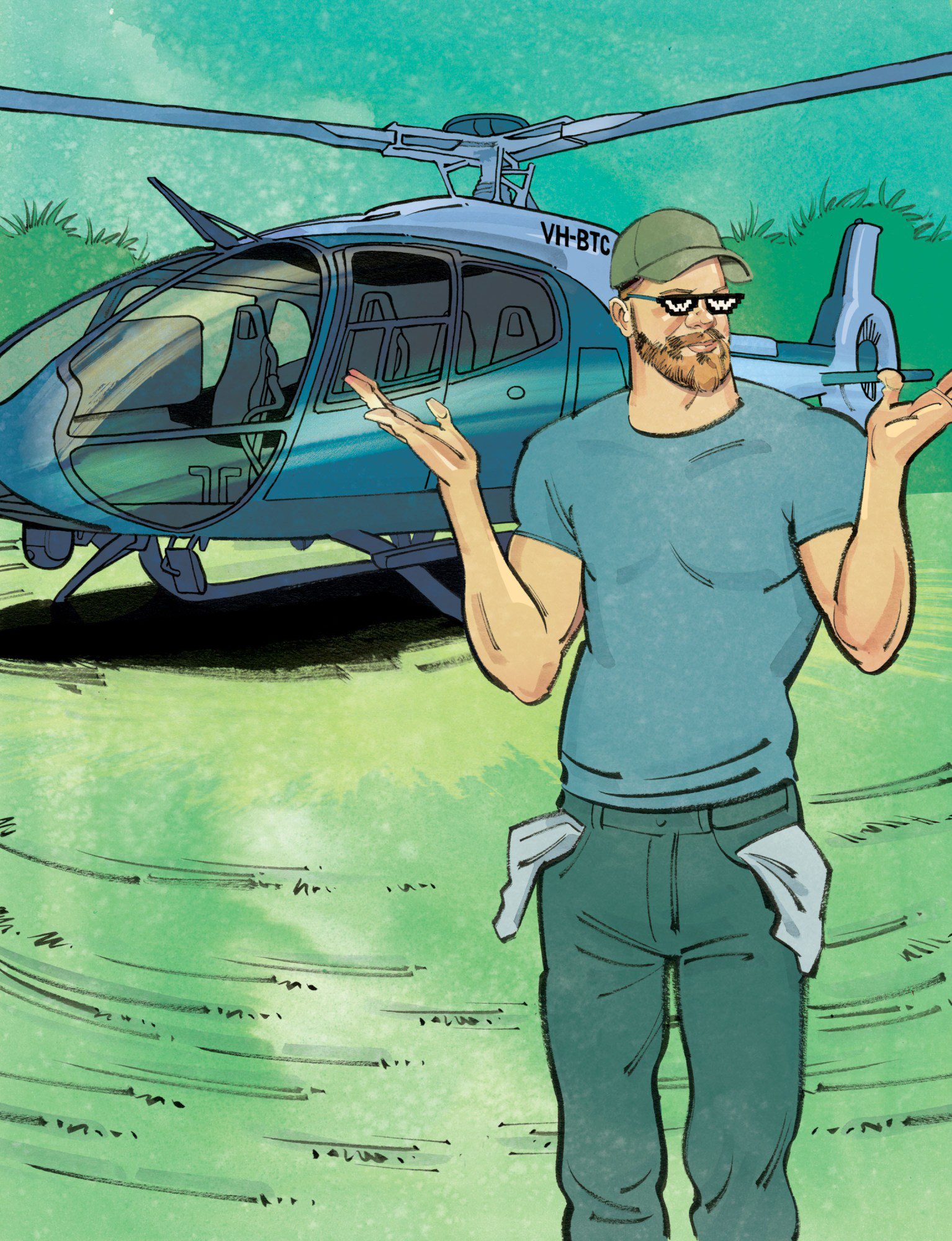

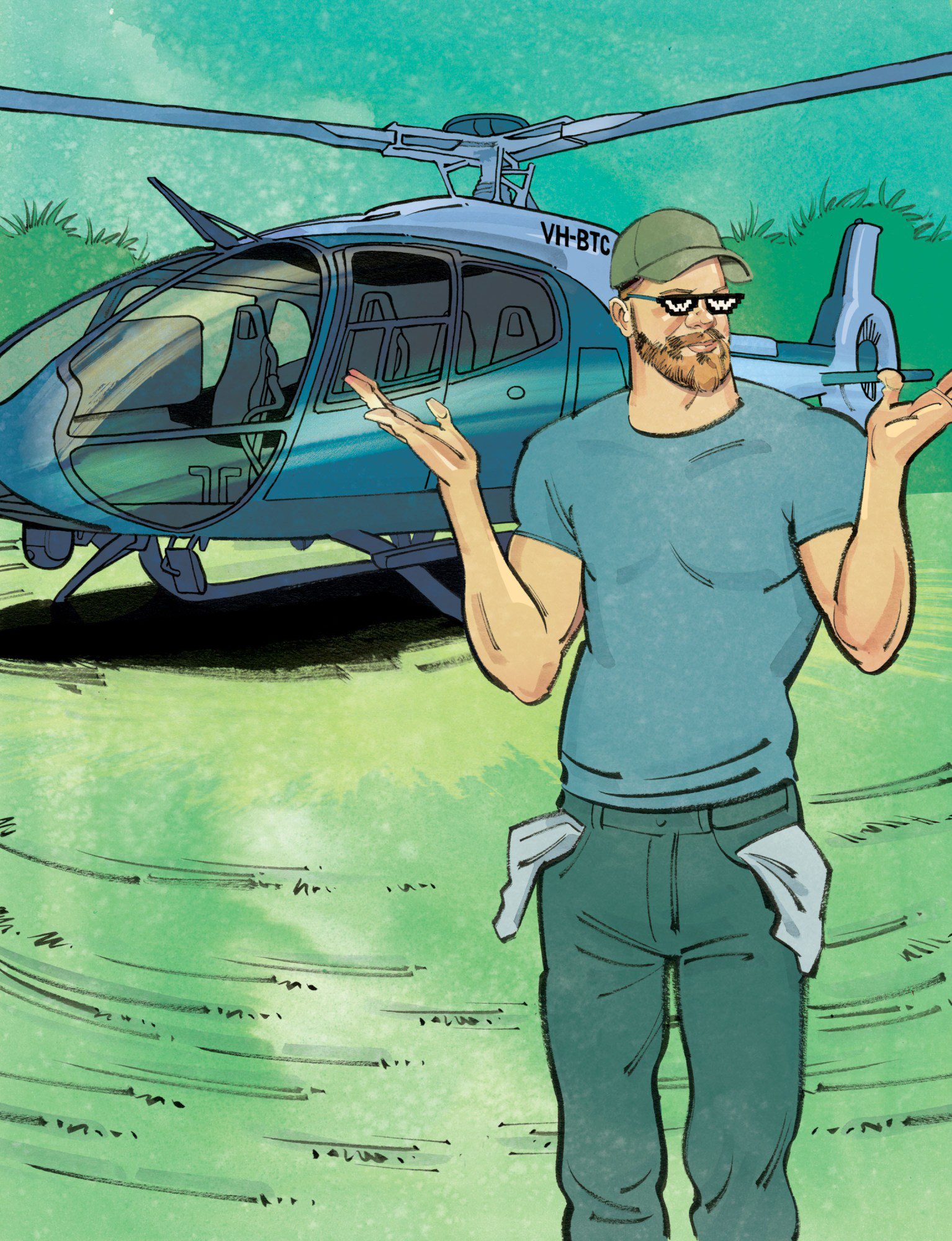

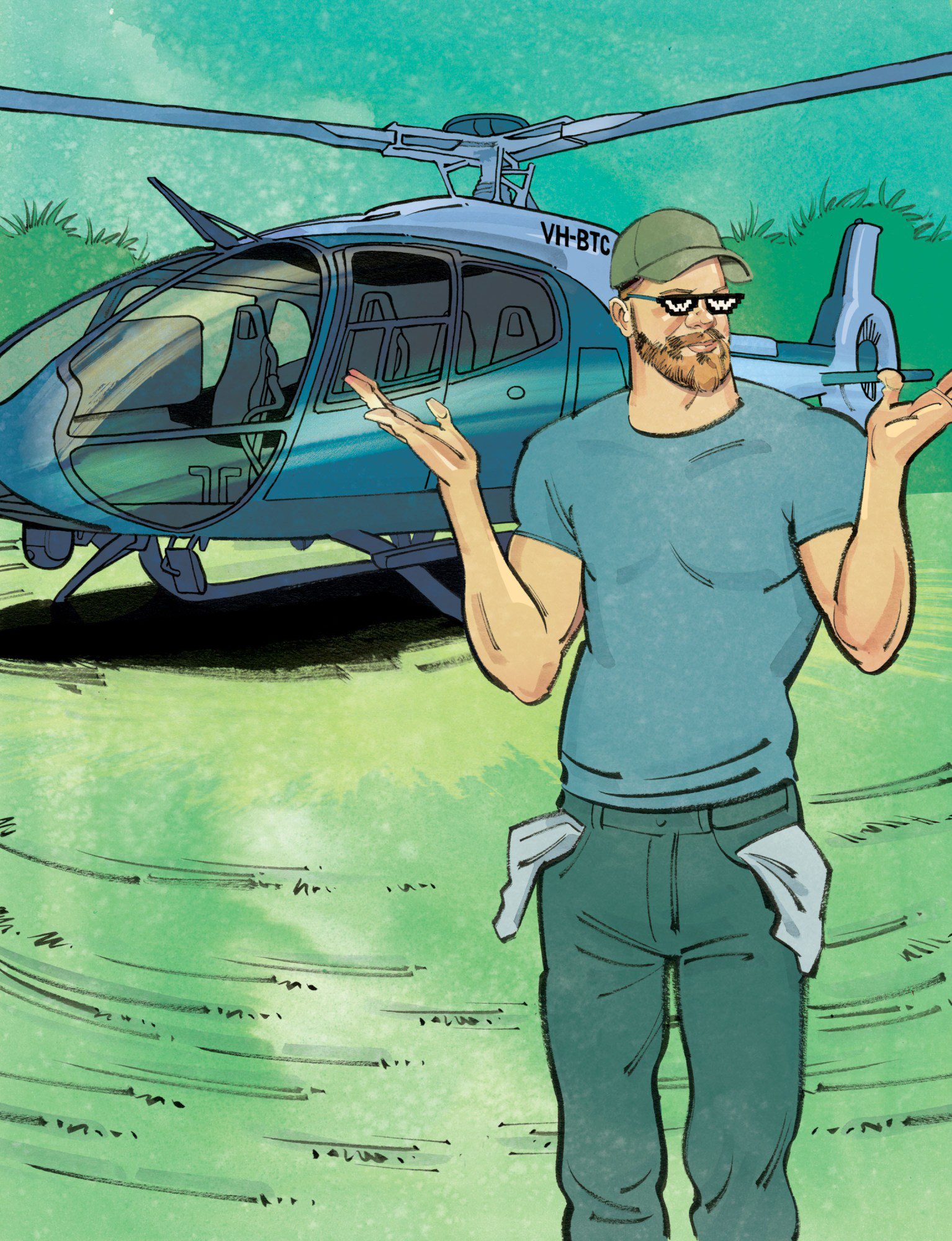

“We’re out of airspace now. We can do whatever we want,” Jean-Paul Thorbjornsen tells me from the pilot’s seat of his Aston Martin helicopter. As we fly over suburbs outside Melbourne, Australia, it’s becoming clear that doing whatever he wants is Thorbjornsen’s MO.

Upper-middle-class homes give way to vineyards, and Thorbjornsen points out our landing spot outside a winery. People visiting for lunch walk outside. “They’re going to ask for a shot now,” he says, used to the attention drawn by his luxury helicopter, emblazoned with the tail letters “BTC” for bitcoin (the price tag of $5 million in Australian dollars—$3.5 million in US dollars today—was perhaps reasonable for someone who claims a previous crypto project made more than AU$400 million, although he also says those funds were tied up in the company).

Thorbjornsen is a founder of THORChain, a blockchain through which users can swap one cryptocurrency for another and earn fees from making those swaps. THORChain is permissionless, so anyone can use it without getting prior approval from a centralized authority. As a decentralized network, the blockchain is built and run by operators located across the globe, most of whom use pseudonyms.

During its early days, Thorbjornsen himself hid behind the pseudonym “leena” and used an AI-generated female image as his avatar. But around March 2024, he revealed that he, an Australian man in his mid-30s, with a rural Catholic upbringing, was the mind behind the blockchain. More or less.

If there is a central question around THORChain, it is this: Exactly who is responsible for its operations? Blockchains as decentralized as THORChain are supposed to offer systems that operate outside the centralized leadership of corruptible governments and financial institutions. If a few people have outsize sway over this decentralized network—one of a handful that operate at such a large scale—it’s one more blemish on the legacy of bitcoin’s promise, which has already been tarnished by capitalistic political frenzy.

Who’s responsible for THORChain matters because in January last year, its users lost more than $200 million worth of their cryptocurrency in US dollars after THORChain transactions and accounts were frozen by a singular admin override, which users believed was not supposed to be possible given the decentralized structure. When the freeze was lifted, some users raced to pull their money out. The following month, a team of North Korean hackers known as the Lazarus Group used THORChain to move roughly $1.2 billion of stolen ethereum taken in the infamous hack of the Dubai-based crypto exchange Bybit.

Thorbjornsen explains away THORChain’s inability to stop the movement of stolen funds, or prevent a bank run, as a function of its decentralized and permissionless nature. The lack of executive powers means that anyone can use the network for any reason, and arguably there’s no one to hold accountable when even the worst goes down.

But when the worst did go down, nearly everyone in the THORChain community, and those paying attention to it in channels like X, pointed their fingers at Thorbjornsen. A lawsuit filed by the THORChain creditors who lost millions in January 2025 names him. A former FBI analyst and North Korea specialist, reflecting on the potential repercussions for helping move stolen funds, told me he wouldn’t want to be in Thorbjornsen’s shoes.

THORChain was designed to make decisions based on votes by node operators, where two-thirds majority rules.

That’s why I traveled to Australia—to see if I could get a handle on where he sees himself and his role in relation to the network he says he founded.

According to Thorbjornsen, he should not be held responsible for either event. THORChain was designed to make decisions based on votes by node operators—people with the computer power, and crypto stake, to run a cluster of servers that process the network’s transactions. In those votes, a two-thirds majority rules.

Then there’s the permissionless part. Anyone can use THORChain to make swaps, which is why it’s been a popular way for widely sanctioned entities such as the government of North Korea to move stolen money. This principle goes back to the cypherpunk roots of bitcoin, a currency that operates outside of nation-states’ rules. THORChain is designed to avoid geopolitical entanglements; that’s what its users like about it.

But there are distinct financial motivations for moving crypto, stolen or not: Node operators earn fees from the funds running through the network. In theory, this incentivizes them to act in the network’s best interests—and, arguably, Thorbjornsen’s interests too, as many assume his wealth is tied to the network’s profits. (Thorbjornsen says it is not, and that it comes instead from “many sources,” including “buying bitcoin back in 2013.”)

Now recent events have raised critical questions, not just about Thorbjornsen’s outsize role in THORChain’s operations, but also about the blockchain’s underlying nature.

If THORChain is decentralized, how was a single operator able to freeze its funds a month before the Bybit hack? Could someone have unilaterally decided to stop the stolen Bybit funds from coming through the network, and chosen not to?

Thorbjornsen insists THORChain is helping realize bitcoin’s original purpose of enabling anyone to transact freely outside the reach of purportedly corrupt governments. Yet the network’s problems suggest that an alternative financial system might not be much better.

Decentralized?

On February 21, 2025, Bybit CEO Ben Zhou got an alarming call from the company’s chief financial officer. About $1.5 billion US of the exchange’s ethereum token, ETH, had been stolen.

The FBI attributed the theft to the Lazarus Group. Typically, criminals will want to convert ETH to bitcoin, which is much easier to convert in turn to cash. Knowing this, the FBI issued a public service announcement on February 26 to “exchanges, bridges … and other virtual asset service providers,” encouraging them to block transactions from accounts related to the hack.

Someone posted that announcement in THORChain’s private, invite-only developer channel on Discord, a chat app used widely by software engineers and gamers. While other crypto exchanges and bridges (which facilitate transactions across different blockchains) heeded the warning, THORChain’s node operators, developers, and invested insiders debated about whether or not to close the trading gates, a decision requiring a majority vote.

“Civil war is a very strong term, but there was a strong rift in the community,” says Boone Wheeler, a US-based crypto enthusiast. In 2021, Wheeler purchased some rune, THORChain’s Norse-mythology-themed native token, and he has been paid to write articles about the network to help advertise it. The rift formed “between people who wanted to stay permissionless,” he says, “and others who wanted to blacklist the funds.”

Wheeler, who says he doesn’t run a node or code for THORChain, fell on the side of remaining permissionless. However, others spoke up for blocking the transfers. THORChain, they argued, wasn’t decentralized enough to keep those running the network safe from law enforcement—especially when those operators were identifiable by their IP addresses, some based in the US.

“We are not the morality police,” someone with the username @Swing_Pop wrote on February 27 in the developer Discord.

THORChain’s design includes up to 120 nodes whose operators manage transactions on the network through a voting process. Anyone with hosting hardware can become an operator by funding nodes with rune as collateral, which provides the network with liquidity. Nodes can respond to a transaction by validating it or doing nothing. While individual transactions can’t be blocked, trading can be halted by a two-thirds majority vote.

Nodes are also penalized for not participating in voting, which the system labels as “bad behavior.” Every 2.5 days, THORChain automatically “churns” nodes out to ensure that no one node gains too much control. The nodes that chose not to validate transactions from the Bybit hack were automatically “churned” out of the system. Thorbjornsen says about 20 or 30 nodes were booted from the network in this way. (Node operators can run multiple nodes, and 120 are rarely running simultaneously; at the time of writing, 55 unique IDs operated 103 nodes.)

By February 27, some node operators were prepared to leave the network altogether. “It’s personally getting beyond my risk tolerance,” wrote @Runetard in the dev Discord. “Sorry to those of the community that feel otherwise. There are a bunch of us holding all the risk and some are getting ready to walk away.”

Even so, the financial incentive for the network operators who remained was significant. As one member of the dev Discord put it earlier that day, $3 million had been “extracted as commission” from the theft by those operating THORChain. “This is wrong!” they wrote.

Thorbjornsen weighed in on this back-and-forth, during which nodes paused and unpaused the network. He now says there was a right and wrong way for node operators to have behaved. “The correct way of doing things,” he says, was for node operators who opposed processing stolen funds to “go offline and … get [themselves] kicked out” rather than try to police who could use THORChain. He also says that while operators could discuss stopping transactions, “there was simply no design in the code that allowed [them] to do that.” However, a since-deleted post from his personal X account on March 3, 2025, stated: “I pushed for all my nodes to unhalt trading [keep trading]. Threatened to yank bond if they didn’t comply. Every single one.” (Thorbjornsen says his social media team ran this account in 2025.)

In an Australian 7 News Spotlight documentary last June, Thorbjornsen estimated that THORChain earned between $5 million and $10 million from the heist.

When asked in that same documentary if he received any of those fees, he replied, “Not directly.” When we spoke, I asked him to elaborate. He said he’s “not a recipient” of any funds THORChain sets aside for developers or marketers, nor does he operate any nodes. He was merely speaking generally, he told me: “All crypto holders profit indirectly off economic activity on any chain.”

Most important to Thorbjornsen was that, despite “huge pressure to shut the protocol down and stop servicing these swaps,” THORChain chugged along. He also notes that the hackers’ tactics, moving fast and splitting funds across multiple addresses, made it difficult to identify “bad swaps.”

Blockchain experts like Nick Carlsen, a former FBI analyst at the blockchain intelligence company TRM Labs, don’t buy this assessment. Other services similar to THORChain were identifying and rejecting these transactions. Had THORChain done the same, Carlsen adds, the stolen funds could have been contained on the Ethereum network, which “would have basically denied North Korea the ability to kick off this laundering process.”

And while THORChain touts its decentralization, in “practical applications” like the Lazarus Group’s theft, “most de-fi [decentralized finance] protocols are centralized,” says Daren Firestone, an attorney who represents crypto industry whistleblowers, citing a 2023 US Treasury Department risk assessment on illicit finance.

With centralization comes culpability, and in these cases, Firestone adds, that comes down to “who profits from [the protocol], so who creates it? But most importantly, who controls it?” Is there someone who can “hit an emergency off switch? … Direct nodes?”

Many answer these questions with Thorbjornsen’s name. “Everyone likes to pass the blame,” he says, even though he wasn’t alone in building THORChain. “In the end, it all comes back to me anyway.”

THORChain origins

According to Thorbjornsen, his story goes like this.

The third of 10 homeschooled children in a “traditional” Catholic household in rural Australia, he spent his days learning math, reading, writing, and studying the Bible. As he got older, he was also responsible for instructing his younger siblings. Wednesday was his day to move the solar panels that powered their home. His parents “installed” a mango and citrus orchard, more to keep nine boys busy than to reap the produce, he says.

“We lived close to a local airfield,” Thorbjornsen says, “and I was always mesmerized by these planes.” He joined the Australian air force and studied engineering, but he says the military left him feeling like “a square peg in a round hole.” He adds that doing things his own way got him frequently “pulled aside” by superiors.

“That’s when I started looking elsewhere,” he says, and in 2013, he found bitcoin. It appealed because it existed “outside the system.”

During the 2017 crypto bull run, Thorbjornsen raised AU$12 million in an initial coin offering for CanYa, a decentralized marketplace he cofounded. CanYa ultimately “died” in 2018, and Thorbjornsen pivoted to a “decentralized liquidity” project that would become THORChain.

He worked with a couple of different developer teams, and then, in 2019, he clicked with an American developer, Chad Barraford, at a hackathon in Germany. Barraford (who declined to be interviewed for this story) was an early public face of THORChain.

Around this time, Thorbjornsen says, “a couple of us helped manage the payroll and early investment funds.” In a 2020 interview, Kai Ansaari, identified as a THORChain “project lead,” wrote, “We’re all contributors … There’s no real ‘lead,’ ‘CEO,’ ‘founder,’ etc.”

In interviews conducted since he came out from behind the “leena” account in 2024, Thorbjornsen has positioned himself as a key lead. He now says his plan had always been to hand over the account, along with command powers and control of THORChain social media accounts, once the blockchain had matured enough to realize its promise of decentralization.

In 2021, he says, he started this process, first by ceasing to use his own rune to back node operators who didn’t have enough to supply their own funding (this can be a way to influence node votes without operating a node yourself). That year, the protocol suffered multiple hacks that resulted in millions of dollars in losses. Nine Realms, a US-incorporated coding company, was brought on to take over THORChain’s development. Thorbjornsen says he passed “leena” over to “other community members” and “left crypto” in 2021, selling “a bunch of bitcoin” and buying the helicopter.

Despite this crypto departure, he came back onto the scene with gusto in 2024 when he revealed himself as the operator of the “leena” account. “For many years, I stayed private because I didn’t want the attention,” he says now.

By early 2024 Thorbjornsen considered the network to be sufficiently decentralized and began advertising it publicly. He started regularly posting videos on his TikTok and YouTube channels (“Two sick videos every week,” in the words of one caption) that showed him piloting his helicopter wearing shirts that read “Thor.”

By November 2024, Thorbjornsen, who describes himself as “a bit flamboyant,” was calling himself THORChain’s CEO (“chief energy officer”) and the “master of the memes” in a video from Binance Blockchain Week, an industry conference in Dubai. You need “strong memetic energy,” he says in the video, “to create the community, to create the cult.” Cults imply centralized leadership, and since outing himself as “leena,” Thorbjornsen has publicly appeared to helm the project, with one interviewer deeming him the “THORChain Satoshi” (an allusion to the pseudonymous creator of bitcoin).

One consequence of going public as a face of the protocol: He’s received death threats. “I stirred it up. Do I regret it? Who knows?” he said when we met in Australia. “It’s caused a lot of chaos.”

But, he added, “this is the bed that I’ve laid.” When we spoke again, months later, he backtracked, saying he “got sucked into” defending THORChain in 2024 and 2025 because he was involved from 2018 to 2021 and has “a perspective on how the protocol operates.”

Centralized?

Ryan Treat, a retired US Army veteran, woke up one morning in January 2025 to some disturbing activity on X. “My heart sank,” he says. THORFi, the THORChain program he’d used to earn interest on the bitcoin he’d planned to save for his retirement, had frozen all accounts—but that didn’t make sense.

THORFi featured a lending and saving program said to give users “complete control” and self-custody of their crypto, meaning they could withdraw it at any time.

Treat was no crypto amateur. He bought his first bitcoin at around “$5 apiece,” he says, and had always kept it off centralized exchanges that would maintain custody of his wallets. He liked THORChain because it claimed to be decentralized and permissionless. “I got into bitcoin because I wanted to have government-less money,” he says.

We were told it was decentralized. Then you wake up one morning and read this guy had an admin mimir.

Many who’d used THORFi lending and saving programs felt similarly. Users I interviewed differentiated THORChain from centralized lending platforms like BlockFi and Celsius, both of which offered extraordinarily high yields before filing for bankruptcy in 2022. “I viewed THORChain as a decentralized system where it was safer,” says Halsey Richartz, a Florida-based THORFi creditor, with “vanilla, 1% passive yield.” Indeed, users I spoke with hadn’t felt the need to monitor their THORFi deposits. “Only your key can be used to withdraw your funds,” the product’s marketing materials insisted. “Savers can withdraw their position to native assets at any time.”

So on January 9, when the “leena” account announced that an admin key had been used to pause withdrawals, it took THORFi users by surprise—and seemed to contradict the marketing messaging around decentralization. “We were told that it was decentralized, and you wake up one morning and read an article that says ‘This guy, JP, had an admin mimir,’” says Treat, referring to Thorbjornsen, “and I’m like, ‘What the fuck is an admin mimir?’”

The admin mimir was one of “a bunch of hard-coded admin keys built into the base code of the system,” says Jonathan Reiter, CEO of the blockchain intelligence company ChainArgos. Those with access to the keys had the ability to make executive decisions on the blockchain—a function many THORChain users didn’t realize could supersede the more democratic decisions made by node votes. These keys had been in THORChain’s code for years and “let you control just about anything,” Reiter adds, including the decision to pause the network during the hacks in 2021 that resulted in a loss of more than $16 million in assets.

Thorbjornsen says that one key was given to Nine Realms, while another was “shared around the original team.” He told me at least three people had them, adding, “I can neither confirm nor deny having access to that mimir key, because there’s no on-chain registry of the keys.”

Regardless of who had access, Thorbjornsen maintains that the admin mimir mechanism was “widely known within the community, and heavily used throughout THORChain’s history” and that any action taken using the keys “could be largely overruled by the nodes.” Indeed, nodes voted to open withdrawals back up shortly after the admin key was used to pause them. By then, those burned by THORFi argue, the damage had already been done. The executive pause to withdrawals, for some, signaled that something was amiss with THORFi. This led to a bank run after the pause was lifted, until the nodes voted to freeze withdrawals permanently (which Thorbjornsen had suggested in a since-deleted post on X), separating users from crypto worth around $200 million in US dollars on January 23. THORFi users were then offered a token called TCY (THORChain Yield), which they could claim with the idea that, when its price rose to $1, they would be made whole. (The price, as of writing, sits at $0.16.)

Who used the key? Thorbjornsen maintains he didn’t do it, but he claims he knows who did and won’t say. He says he’d handed over the “leena” account and doesn’t “have access to any of the core components of the system,” nor has he for “at least three years.” He implies that whoever controlled “leena” at the time used the admin key to pause network withdrawals.

A video released by Nine Realms on February 20, 2025, names Thorbjornsen as the activator of the key, stating, “JP ended up pausing lenders and savers, preventing withdrawals so that we can work out … [a] payback plan on them.” Thorbjornsen told me the video was “not factual.”

Multiple blockchain analysts told me it would be extremely difficult to determine who used the admin mimir key. A month after it was used to pause the network, THORChain said the key had been “removed from the network.” At least you can’t find the words “admin mimir” in THORChain’s base code; I’ve looked.

Culpability

After the debacle of the THORFi withdrawal freeze, Richartz says, he tried to file reports with the Miami-Dade Police Department, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, the FBI, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, the Federal Trade Commission, and Interpol. When we spoke in November, he still hadn’t been able to file with the city of Miami. They told him to try small claims court.

“I was like, no, you don’t understand … a post office box in Switzerland is the company address,” he says. “It underscored to me how little law enforcement even knows about these crimes.”

As for the Bybit hack, at least one government has retaliated against those who facilitate blockchain projects. Last April German authorities shut down eXch, an exchange suspected of using THORChain to process funds Lazarus stole from Bybit, says Julia Gottesman, cofounder and head of investigations at the cybersecurity group zeroShadow. Australia, she adds, where Thorbjornsen was based, has been “slow to try to engage with the crypto community, or any regulations.”

In response to requests for comment, Australia’s Department of Home Affairs wrote that at the end of March 2026, the country’s regulatory powers will expand to include “exchanges between the same type of cryptocurrency and transfers between different types.” They did not comment on specific investigations.

Crypto and finance experts disagree about whether THORChain engaged in money laundering, defined by the UN as “the processing of criminal proceeds to disguise their illegal origin.” But some think it fits the definition.

Shlomit Wagman, a Harvard fellow and former head of Israel’s anti-money-laundering agency and its delegation to the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), thinks the Bybit activity was money laundering because THORChain helped the hackers “transfer the funds in an unsupervised manner, completely outside of the scope of regulated or supervised activity.”

And by helping with conversions, Carlsen says, THORChain enabled bad actors to turn stolen crypto into usable currency. “People like [Thorbjornsen] have a personal degree of culpability in sustaining the North Korean government,” he says. Thorbjornsen counters that THORChain is “open-source infrastructure.”

Meanwhile, just days after the hack, Bybit issued a 10% bounty on any funds recovered. As of mid-January this year, between $100 million and $500 million worth of those funds in US dollars remain unaccounted for, according to Gottesman of zeroShadow, which was hired by Bybit to recover funds following the hack.

Thorbjornsen hacked

For Thorbjornsen, it’s just another day at the casino. That’s the comparison he made during his regrettable 7 News Spotlight interview about the Bybit heist, and he repeated it when we met. “You go to a casino, you play a few games, you expect to lose,” he told me. “When you do actually go to zero, don’t cry.”

Thorbjornsen, it should be noted, has lost at the casino himself.

In September, he says, he got a Telegram message from a friend, inviting him to a Zoom meeting. He accepted and participated in a call with people who had “American voices.”

Ultimately, Thorbjornsen describes himself as a guy who’s had a bad year, fending off “threat vectors” left and right.

After the meeting, Thorbjornsen learned that his friend’s Telegram had been hacked. Whoever was responsible had used the Zoom link to remotely install software on Thorbjornsen’s computer, which “got access to everything”—his email, his crypto wallets, a bitcoin-based retirement fund. It cost him at least $1.2 million. The blockchain sleuth known as ZachXBT traced the funds and attributed the hack to North Korea.

ZachXBT called it “poetic.”

Ultimately, Thorbjornsen describes himself as a guy who’s had a bad year. He says he had to liquidate his crypto assets because he’s dealing with the fallout of a recent divorce. He also feels he is fending off “threat vectors” left and right. More than once, he asked if I was a private investigator masquerading as a journalist.

Still, his many contradictions don’t inspire confidence. He doesn’t have any more crypto assets, he says. However, the crypto wallet he shared with me so I could pay him back for lunch showed that it contained assets worth more than $143,000 in US dollars. He now says it wasn’t his wallet. He says he doesn’t control THORChain’s social media, but he’d also told me that he runs the @THORChain X account (later backtracking and saying the account is “delegated” to him for trickier questions).

He insists that he does not care about money. He says that in the robot future, the AI-powered hive mind will become our benevolent overlord, rendering money obsolete, so why give it much thought? Yet as we flew back from the vineyard, he pointed out his new house from the helicopter. It resembles a compound. He says he lives there with his new wife.

Multiple people I spoke with about Thorbjornsen before I met him warned me he wasn’t trustworthy, and he’s undeniably made fishy statements. For instance, the presence of a North Korean flag in a row of decals on the tail of his helicopter suggested an affinity with the country for which THORChain has processed so much crypto. Thorbjornsen insists he had requested the flag of Australia’s Norfolk Island, calling the mix-up “a complete coincidence.” The flags were gone by the time of our flight, apparently removed during a recent repair.

“Money is a meme,” he says. “Money does not exist.” Meme or not, it’s had real repercussions for those who have interacted with THORChain, and those who wound up losing have been looking for someone to blame.

When I spoke with Thorbjornsen again in January, he appeared increasingly concerned that he is that someone. He’s spending more time in Singapore, he told me. Singapore happens to have historically denied extraditions to the US for money-laundering prosecutions.

Jessica Klein is a Philadelphia-based freelance journalist covering intimate partner violence, cryptocurrency, and other topics.