It’s a thought that occurs to every video-game player at some point: What if the weird, hyper-focused state I enter when playing in virtual worlds could somehow be applied to the real one?

Often pondered during especially challenging or tedious tasks in meatspace (writing essays, say, or doing your taxes), it’s an eminently reasonable question to ask. Life, after all, is hard. And while video games are too, there’s something almost magical about the way they can promote sustained bouts of superhuman concentration and resolve.

For some, this phenomenon leads to an interest in flow states and immersion. For others, it’s simply a reason to play more games. For a handful of consultants, startup gurus, and game designers in the late 2000s, it became the key to unlocking our true human potential.

In her 2010 TED Talk, “Gaming Can Make a Better World,” the game designer Jane McGonigal called this engaged state “blissful productivity.” “There’s a reason why the average World of Warcraft gamer plays for 22 hours a week,” she said. “It’s because we know when we’re playing a game that we’re actually happier working hard than we are relaxing or hanging out. We know that we are optimized as human beings to do hard and meaningful work. And gamers are willing to work hard all the time.”

McGonigal’s basic pitch was this: By making the real world more like a video game, we could harness the blissful productivity of millions of people and direct it at some of humanity’s thorniest problems—things like poverty, obesity, and climate change. The exact details of how to accomplish this were a bit vague (play more games?), but her objective was clear: “My goal for the next decade is to try to make it as easy to save the world in real life as it is to save the world in online games.”

While the word “gamification” never came up during her talk, by that time anyone following the big-ideas circuit (TED, South by Southwest, DICE, etc.) or using the new Foursquare app would have been familiar with the basic idea. Broadly defined as the application of game design elements and principles to non-game activities—think points, levels, missions, badges, leaderboards, reinforcement loops, and so on—gamification was already being hawked as a revolutionary new tool for transforming education, work, health and fitness, and countless other parts of life.

Instead of liberating us, gamification turned out to be just another tool for coercion, distraction, and control.

Adding “world-saving” to the list of potential benefits was perhaps inevitable, given the prevalence of that theme in video-game storylines. But it also spoke to gamification’s foundational premise: the idea that reality is somehow broken. According to McGonigal and other gamification boosters, the real world is insufficiently engaging and motivating, and too often it fails to make us happy. Gamification promises to remedy this design flawby engineering a new reality, one that transforms the dull, difficult, and depressing parts of life into something fun and inspiring. Studying for exams, doing household chores, flossing, exercising, learning a new language—there was no limit to the tasks that could be turned into games, making everything IRL better.

Today, we live in an undeniably gamified world. We stand up and move around to close colorful rings and earn achievement badges on our smartwatches; we meditate and sleep to recharge our body batteries; we plant virtual trees to be more productive; we chase “likes” and “karma” on social media sites and try to swipe our way toward social connection. And yet for all the crude gamelike elements that have been grafted onto our lives, the more hopeful and collaborative world that gamification promised more than a decade ago seems as far away as ever. Instead of liberating us from drudgery and maximizing our potential, gamification turned out to be just another tool for coercion, distraction, and control.

Con game

This was not an unforeseeable outcome. From the start, a small but vocal group of journalists and game designers warned against the fairy-tale thinking and facile view of video games that they saw in the concept of gamification. Adrian Hon, author of You’ve Been Played, a recent book that chronicles its dangers, was one of them.

“As someone who was building so-called ‘serious games’ at the time the concept was taking off, I knew that a lot of the claims being made around the possibility of games to transform people’s behaviors and change the world were completely overblown,” he says.

Hon isn’t some knee-jerk polemicist. A trained neuroscientist who switched to a career in game design and development, he’s the co-creator of Zombies, Run!—one of the most popular gamified fitness apps in the world. While he still believes games can benefit and enrich aspects of our nongaming lives, Hon says a one-size-fits-all approach is bound to fail. For this reason, he’s firmly against both the superficial layering of generic points, leaderboards, and missions atop everyday activities and the more coercive forms of gamification that have invaded the workplace.

Ironically, it’s these broad and varied uses that make criticizing the practice so difficult. As Hon notes in his book, gamification has always been a fast-moving target, varying dramatically in scale, scope, and technology over the years. As the concept has evolved, so too have its applications, whether you think of the gambling mechanics that now encourage users of dating apps to keep swiping, the “quests” that compel exhausted Uber drivers to complete just a few more trips, or the utopian ambition of using gamification to save the world.

In the same way that AI’s lack of a fixed definition today makes it easy to dismiss any one critique for not addressing some other potential definition of it, so too do gamification’s varied interpretations. “I remember giving talks critical of gamification at gamification conferences, and people would come up to me afterwards and be like, ‘Yeah, bad gamification is bad, right? But we’re doing good gamification,’” says Hon. (They weren’t.)

For some critics, the very idea of “good gamification” was anathema. Their main gripe with the term and practice was, and remains, that it has little to nothing to do with actual games.

“A game is about play and disruption and creativity and ambiguity and surprise,” wrote the late Jeff Watson, a game designer, writer, and educator who taught at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts. Gamification is about the opposite—the known, the badgeable, the quantifiable. “It’s about ‘checking in,’ being tracked … [and] becoming more regimented. It’s a surveillance and discipline system—a wolf in sheep’s clothing. Beware its lure.”

Another game designer, Margaret Robertson, has argued that gamification should really be called “pointsification,” writing: “What we’re currently terming gamification is in fact the process of taking the thing that is least essential to games and representing it as the core of the experience. Points and badges have no closer a relationship to games than they do to websites and fitness apps and loyalty cards.”

For the author and game designer Ian Bogost, the entire concept amounted to a marketing gimmick. In a now-famous essay published in the Atlantic in 2011, he likened gamification to the moral philosopher Harry Frankfurt’s definition of bullshit—that is, a strategy intended to persuade or coerce without regard for actual truth.

“The idea of learning or borrowing lessons from game design and applying them to other areas was never the issue for me,” Bogost told me. “Rather, it was not doing that—acknowledging that there’s something mysterious, powerful, and compelling about games, but rather than doing the hard work, doing no work at all and absconding with the spirit of the form.”

Gaming the system

So how did a misleading term for a misunderstood process that’s probably just bullshit come to infiltrate virtually every part of our lives? There’s no one simple answer. But gamification’s meteoric rise starts to make a lot more sense when you look at the period that gave birth to the idea.

The late 2000s and early 2010s were, as many have noted, a kind of high-water mark for techno-optimism. For people both inside the tech industry and out, there was a sense that humanity had finally wrapped its arms around a difficult set of problems, and that technology was going to help us squeeze out some solutions. The Arab Spring bloomed in 2011 with the help of platforms like Facebook and Twitter, money was more or less free, and “____ can save the world” articles were legion (with ____ being everything from “eating bugs” to “design thinking”).

This was also the era that produced the 10,000-hours rule of success, the long tail, the four-hour workweek, the wisdom of crowds, nudge theory, and a number of other highly simplistic (or, often, flat-out wrong) theories about the way humans, the internet, and the world work.

“All of a sudden you had VC money and all sorts of important, high-net-worth people showing up at game developer conferences.”

Ian Bogost, author and game designer

Adding video games to this heady stew of optimism gave the game industry something it had long sought but never achieved: legitimacy. Even with games ascendant in popular culture—and on track to eclipse both the film and music industries in terms of revenue—they still were largely seen as a frivolous, productivity-squandering, violence-encouraging form of entertainment. Seemingly overnight, gamification changed all that.

“There was definitely this black-sheep mentality in the game development community—the sense that what we had been doing for decades was just a joke to people,” says Bogost. “All of a sudden you had VC money and all sorts of important, high-net-worth people showing up at game developer conferences, and it was like, ‘Finally someone’s noticing. They realize that we have something to offer.’”

This wasn’t just flattering; it was intoxicating. Gamification took a derided pursuit and recast it as a force for positive change, a way to make the real world better. While enthusiastic calls to “build a game layer on top of reality” may sound dystopian to many of us today, the sentiment didn’t necessarily have the same ominous undertones at the end of the aughts.

Combine the cultural recasting of games with an array of cheaper and faster technologies—GPS, ubiquitous and reliable mobile internet, powerful smartphones, Web 2.0 tools and services—and you arguably had all the ingredients needed for gamification’s rise. In a very real sense, reality in 2010 was ready to be gamified. Or to put it a slightly different way: Gamification was an idea perfectly suited for its moment.

Gaming behavior

Fine, you might be asking at this point, but does it work? Surely, companies like Apple, Uber, Strava, Microsoft, Garmin, and others wouldn’t bother gamifying their products and services if there were no evidence of the strategy’s efficacy. The answer to the question, unfortunately, is super annoying: Define work.

Because gamification is so pervasive and varied, it’s hard to address its effectiveness in any direct or comprehensive way. But one can confidently say this: Gamification did not save the world. Climate change still exists. As do obesity, poverty, and war. Much of generic gamification’s power supposedly resides in its ability to nudge or steer us toward, or away from, certain behaviors using competition (challenges and leaderboards), rewards (points and achievement badges), and other sources of positive and negative feedback.

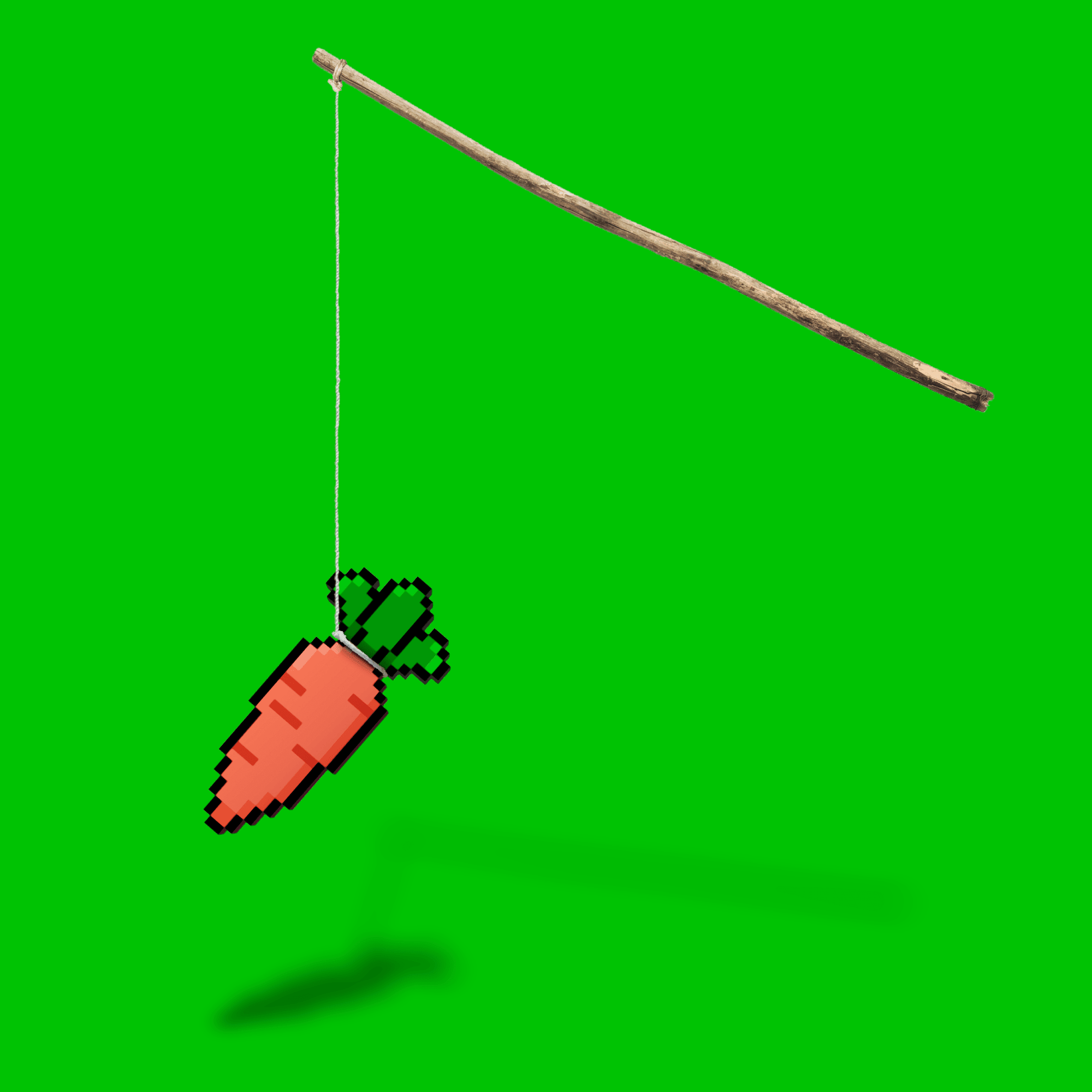

Gamification is, and has always been, a way to induce specific behaviors in people using virtual carrots and sticks.

On that front, the results are mixed. Nudge theory lost much of its shine with academics in 2022 after a meta-analysis of previous studies concluded that, after correcting for publication bias, there wasn’t much evidence it worked to change behavior at all. Still, there are a lot of ways to nudge and a lot of behaviors to modify. The fact remains that plenty of people claim to be highly motivated to close their rings, earn their sleep crowns, or hit or exceed some increasingly ridiculous number of steps on their Fitbits (see humorist David Sedaris).

Sebastian Deterding, a leading researcher in the field, argues that gamification can work, but its successes tend to be really hard to replicate. Not only do academics not know what works, when, and how, according to Deterding, but “we mostly have just-so stories without data or empirical testing.”

In truth, gamification acolytes were always pulling from an old playbook—one that dates back to the early 20th century. Then, behaviorists like John Watson and B.F. Skinner saw human behaviors (a category that for Skinner included thoughts, actions, feelings, and emotions) not as the products of internal mental states or cognitive processes but, rather, as the result of external forces—forces that could conveniently be manipulated.

If Skinner’s theory of operant conditioning, which doled out rewards to positively reinforce certain behaviors, sounds a lot like Amazon’s “Fulfillment Center Games,” which dole out rewards to compel workers to work harder, faster, and longer—well, that’s not a coincidence. Gamification is, and has always been, a way to induce specific behaviors in people using virtual carrots and sticks.

Sometimes this may work; other times not. But ultimately, as Hon points out, the question of efficacy may be beside the point. “There is no before or after to compare against if your life is always being gamified,” he writes. “There isn’t even a static form of gamification that can be measured, since the design of coercive gamification is always changing, a moving target that only goes toward greater and more granular intrusion.”

The game of life

Like any other art form, video games offer a staggering array of possibilities. They can educate, entertain, foster social connection, inspire, and encourage us to see the world in different ways. Some of the best ones manage to do all of this at once.

Yet for many of us, there’s the sense today that we’re stuck playing an exhausting game that we didn’t opt into. This one assumes that our behaviors can be changed with shiny digital baubles, constant artificial competition, and meaningless prizes. Even more insulting, the game acts as if it exists for our benefit—promising to make us fitter, happier, and more productive—when in truth it’s really serving the commercial and business interests of its makers.

Metaphors can be an imperfect but necessary way to make sense of the world. Today, it’s not uncommon to hear talk of leveling up, having a God Mode mindset, gaining XP, and turning life’s difficulty settings up (or down). But the metaphor that resonates most for me—the one that seems to neatly capture our current predicament—is that of the NPC, or non-player character.

NPCs are the “Sisyphean machines” of video games, programmed to follow a defined script forever and never question or deviate. They’re background players in someone else’s story, typically tasked with furthering a specific plotline or performing some manual labor. To call someone an NPC in real life is to accuse them of just going through the motions, not thinking for themselves, not being able to make their own decisions. This, for me, is gamification’s real end result. It’s acquiescence pretending to be empowerment. It strips away the very thing that makes games unique—a sense of agency—and then tries to mask that with crude stand-ins for accomplishment.

So what can we do? Given the reach and pervasiveness of gamification, critiquing it at this point can feel a little pointless, like railing against capitalism. And yet its own failed promises may point the way to a possible respite. If gamifying the world has turned our lives into a bad version of a video game, perhaps this is the perfect moment to reacquaint ourselves with why actual video games are great in the first place. Maybe, to borrow an idea from McGonigal, we should all start playing better games.

Bryan Gardiner is a writer based in Oakland, California.