The messy quest to replace drugs with electricity

In the early 2010s, electricity seemed poised for a hostile takeover of your doctor’s office. Research into how the nervous system controls the immune response was gaining traction. And that had opened the door to the possibility of hacking into the body’s circuitry and thereby controlling a host of chronic diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, and diabetes, as if the immune system were as reprogrammable as a computer.

To do that you’d need a new class of implant: an “electroceutical,” formally introduced in an article in Nature in 2013. “What we are doing is developing devices to replace drugs,” coauthor and neurosurgeon Kevin Tracey told Wired UK. These would become a “mainstay of medical treatment.” No more messy side effects. And no more guessing whether a drug would work differently for you and someone else.

There was money behind this vision: the British pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline announced a $1 million research prize, a $50 million venture fund, and an ambitious program to fund 40 researchers who would identify neural pathways that could control specific diseases. And the company had an aggressive timeline in mind. As one GlaxoSmithKline executive put it, the goal was to have “the first medicine that speaks the electrical language of our body ready for approval by the end of this decade.”

In the 10 years or so since, around a billion dollars has accreted around the effort by way of direct and indirect funding. Some implants developed in that electroceutical push have trickled into clinical trials, and two companies affiliated with GlaxoSmithKline and Tracey are ramping up for splashy announcements later this year. We don’t know much yet about how successful the trials now underway have been. But widespread regulatory approval of the sorts of devices envisioned in 2013—devices that could be applied to a broad range of chronic diseases—is not imminent. Electroceuticals are a long way from fomenting a revolution in medical care.

At the same time, a new area of science has begun to cohere around another way of using electricity to intervene in the body. Instead of focusing only on the nervous system—the highway that carries electrical messages between the brain and the body—a growing number of researchers are finding clever ways to electrically manipulate cells elsewhere in the body, such as skin and kidney cells, more directly than ever before. Their work suggests that this approach could match the early promise of electroceuticals, yielding fast-healing bioelectric bandages, novel approaches to treating autoimmune disorders, new ways of repairing nerve damage, and even better treatments for cancer. However, such ventures have not benefited from investment largesse. Investors tend to understand the relationship between biology and electricity only in the context of the nervous system. “These assumptions come from biases and blind spots that were baked in during 100 years of neuroscience,” says Michael Levin, a bioelectricity researcher at Tufts University.

Electrical implants have already had success in targeting specific problems like epilepsy, sleep apnea, and catastrophic bowel dysfunction. But the broader vision of replacing drugs with nerve-zapping devices, especially ones that alter the immune system, has been slower to materialize. In some cases, perhaps the nervous system is not the best way in. Looking beyond this singular locus of control might open the way for a wider suite of electromedical interventions—especially if the nervous system proves less amenable to hacking than originally advertised.

How it started

GSK’s ambitious electroceutical venture was a response to an increasingly onerous problem: 90% of drugs fall down during the obstacle race through clinical trials. A new drug that does squeak by can cost $2 billion or $3 billion and take 10 to 15 years to bring to market, a galling return on investment. The flaw is in the delivery system. The way we administer healing chemicals hasn’t had much of a conceptual overhaul since the Renaissance physician Paracelsus: ingest or inject. Both approaches have built-in inefficiencies: it takes a long time for the drugs to build up in your system, and they can disperse widely before arriving in diluted form at their target, which may make them useless where they are needed and toxic elsewhere. Tracey and Kristoffer Famm, a coauthor on the Nature article who was then a VP at GlaxoSmithKline, explained on the publicity circuit that electroceuticals would solve these problems—acting more quickly and working only in the precise spot where the intervention was needed. After 500 years, finally, here was a new idea.

Well … new-ish. Electrically stimulating the nervous system had racked up promising successes since the mid-20th century. For example, the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease had been treated via deep brain stimulation, and intractable pain via spinal stimulation. However, these interventions could not be undertaken lightly; the implants needed to be placed in the spine or the brain, a daunting prospect to entertain. In other words, this idea would never be a money spinner.

What got GSK excited was recent evidence that health could be more broadly controlled, and by nerves that were easier to access. By the dawn of the 21st century it had become clear you could tap the nervous system in a way that carried fewer risks and more rewards. That was because of findings suggesting that the peripheral nervous system—essentially, everything but the brain and spine—had much wider influence than previously believed.

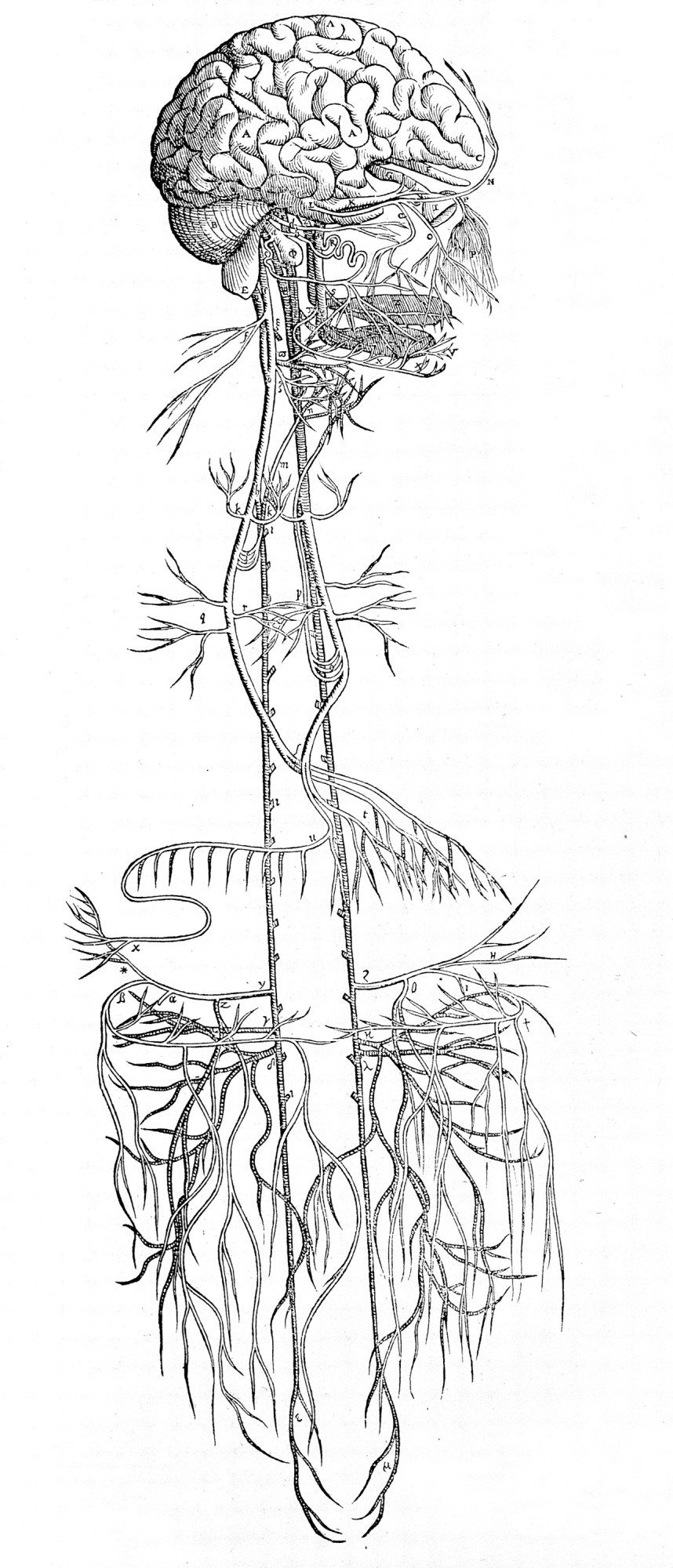

The prevailing wisdom had long been that the peripheral nervous system had only one job: sensory awareness of the outside world. This information is ferried to the brain along many little neural tributaries that emerge from the extremities and organs, most of which converge into a single main avenue at the torso: the vagus nerve.

Starting in the 1990s, research by Linda Watkins, a neuroscientist leading a team at the University of Colorado, Boulder, suggested that this main superhighway of the peripheral nervous system was not a one-way street after all. Instead it seemed to carry message traffic in both directions, not just into the brain but from the brain back into all those organs. Furthermore, it appeared that this comms link allows the brain to exert some control over the immune system—for example, stoking a fever in response to an infection.

And unlike the brain or spinal cord, the vagus nerve is comparatively easy to access: its path to and from the brain stem runs close to the surface of the neck, along a big cable on either side. You could just pop an electrode on it—typically on the left branch—and get zapping.

Meddling with the flow of traffic up the vagus nerve in this way had successfully treated issues in the brain, specifically epilepsy and treatment-resistant depression (and electrical implants for those applications were approved by the FDA around the turn of the millennium). But the insights from Watkins’s team put the down direction in play.

It was Kevin Tracey who joined all these dots, after which it did not take long for him to become the public face of research on vagus nerve stimulation. During the 2000s, he showed that electrically stimulating the nerve calmed inflammation in animals. This “inflammatory reflex,” as he came to call it, implied that the vagus nerve could act as a switch capable of turning off a wide range of diseases, essentially hacking the immune system. In 2007, while based at what is now called the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, in New York, he spun his insights off into a Boston startup called SetPoint Medical. Its aim was to develop devices to flip this switch and bring relief, starting with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis.

By 2012, a coordinated relationship had developed between GSK, Tracey, and US government agencies. Tracey says that Famm and others contacted him “to help them on that Nature article.” A year later the electroceuticals road map was ready to be presented to the public.

The story the researchers told about the future was elegant and simple. It was illustrated by a tale Tracey recounted frequently on the publicity circuit, of a first-in-human case study SetPoint had coordinated at the University of Amsterdam’s Academic Medical Center. That team had implanted a vagus nerve stimulator in a man suffering from rheumatoid arthritis. The stimulation triggered his spleen to release a chemical called acetylcholine. This in turn told the cells in the spleen to switch off production of inflammatory molecules called cytokines. For this man, the approach worked well enough to let him resume his job, play with his kids, and even take up his old hobbies. In fact, his overenthusiastic resumption of his former activities resulted in a sports injury, as Tracey delighted in recounting for reporters and conferences.

Such case studies opened the money spigot. The combination of a wider range of disease targets and less risky surgical targets was an investor’s love language. Where deep brain stimulation and other invasive implants had been limited to rare, obscure, and catastrophic problems, this new interface with the body promised many more customers: the chronic diseases now on the table are much more prevalent, including not only rheumatoid arthritis but diabetes, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, lupus, and many other autoimmune disorders. GSK launched an investment arm it dubbed Action Potential Venture Capital Limited, with $50 million in the coffers to invest in the technologies and companies that would turn the futuristic vision of electroceuticals into reality. Its inaugural investment was a $5 million stake in SetPoint.

If you were superstitious, what happened next might have looked like an omen. The word “electroceutical” already belonged to someone else—a company called Ivivi Technologies had trademarked it in 2008. “I am fairly certain we sent them a letter soon after they started that campaign, to alert them of our trademark,” says Sean Hagberg, a cofounder and then chief science officer at the company. Today neither GSK nor SetPoint can officially call its tech “electroceuticals,” and both refer to the implants they are developing as “bioelectronic medicine.” However, this umbrella term encompasses a wide range of other interventions, some quite well established, including brain implants, spine implants, hypoglossal nerve stimulation for sleep apnea (which targets a motor nerve running through the vagus), and other peripheral-nervous-system implants, including those for people with severe gastric disorders.

The next problem appeared in short order: how to target the correct nerve. The vagus nerve has roughly 100,000 fibers packed tightly within it, says Kip Ludwig, who was then with the US National Institutes of Health and now co-directs the Wisconsin Institute for Translational Neuroengineering at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. These myriad fibers connect to many different organs, including the larynx and lower airways, and electrical fields are not precise enough to hit a single one without hitting many of its neighbors (as Ludwig puts it, “electric fields [are] really promiscuous”).

This explains why a wholesale zap of the entire bundle had long been associated with unpredictable “on-target effects” and unpleasant “off-target effects,” which is another way of saying it didn’t always work and could carry side effects that ranged from the irritating, like a chronic cough, to the life-altering, including headaches and a shortness of breath that is better described as air hunger. Singling out the fibers that led to the particular organ you were after was hard for another reason, too: the existing maps of the human peripheral nervous system were old and quite limited. Such a low-resolution road map wouldn’t be sufficient to get a signal from the highway all the way to a destination.

In 2014, to remedy this and generally advance the field of peripheral nerve stimulation, the NIH announced a research initiative known as SPARC—Stimulating Peripheral Activity to Relieve Conditions—with the aim of pouring $248 million into research on new ways to exploit the nervous system’s electrical pathways for medicine. “My job,” says Gene Civillico, who managed the program until 2021, “was to do a program related to electroceuticals that used the NIH policy options that were available to us to try to make something catalytic happen.” The idea was to make neural anatomical maps and sort out the consequences of following various paths. After the organs were mapped, Civillico says, the next step was to figure out which nerve circuit would stimulate them, and settle on an access point—“And the access point should be the vagus nerve, because that’s where the most interest is.”

Two years later, as SPARC began to distribute its funds, companies moved forward with plans for the first generation of implants. GSK teamed up with Verily (formerly Google Life Sciences) on a $715 million research initiative they called Galvani Bioelectronics, with Famm at its helm as president. SetPoint, which had relocated to Valencia, California, moved to an expanded location, a campus that had once housed a secret Lockheed R&D facility.

How it’s going

Ten years after electroceuticals entered (and then quickly departed) the lexicon, the SPARC program has yielded important information about the electrical particulars of the peripheral nervous system. Its maps have illuminated nodes that are both surgically attractive and medically relevant. It has funded a global constellation of academic researchers. But its insights will be useful for the next generation of implants, not those in trials today.

Today’s implants, from SetPoint and Galvani, will be in the news later this year. Though SetPoint estimates that an extended study of its phase III clinical trial will conclude in 2027, the primary outcomes will be released this summer, says Ankit Shah, a marketing VP at SetPoint. And while Galvani’s trial will conclude in 2029, Famm says, the company is “coming to an exciting point” and will publish patient data later in 2024.

The results could be interpreted as a referendum on the two companies’ different approaches. Both devices treat rheumatoid arthritis, and both target the immune system via the peripheral nervous system, but that’s where the similarities end. SetPoint’s device uses a clamshell design that cuffs around the vagus nerve at the neck. It stimulates for just one minute, once per day. SetPoint representatives say they have never seen the sorts of side effects that have resulted from using such stimulators to treat epilepsy. But if anyone did experience those described by other researchers—even vomiting and headaches—they might be tolerable if they only lasted a minute.

But why not avoid the vagus nerve entirely? Galvani is using a more precise implant that targets the “end organ” of the spleen. If the vagus nerve can be considered the main highway of the peripheral nervous system, an end organ is essentially a particular organ’s “driveway.” Galvani’s target is the point where the splenic nerve (having split off from a system connected to the vagus highway) meets the spleen.

To zero in on such a specific target, the company has sacrificed ease of access. Its implant, which is about the size of a house key, is laparoscopically injected into the body through the belly button. Famm says if this approach works for rheumatoid arthritis, then it will likely translate for all autoimmune disorders. Highlighting this clinical trial in 2022, he told Nature Reviews: “This is what makes the next 10 years exciting.”

Perhaps more so for researchers than for patients, however. Even as Galvani and SetPoint prepare talking points, other SPARC-funded groups are still pondering the sorts of research questions suggesting that the best technological interface with the immune system is still up for debate. At the moment, electroceuticals are in the spotlight, but they have a long way to go, says Vaughan Macefield, a neurophysiologist at Monash University in Australia, whose work is funded by a more recent $21 million SPARC grant: “It’s an elegant idea, [but] there are conflicting views.”

Macefield doesn’t think zapping the entire bundle is a good idea. Many researchers are working on ways to get more selective about which particular fibers of the vagus nerve they stimulate. Some are designing novel electrodes that will penetrate specific fibers rather than clamping around all of them. Others are trying to hit the vagus at deeper points in the abdomen. Indeed, some aren’t sure either electricity or an implant is a necessary ingredient of the “electroceutical.” Instead, they are pivoting from electrical stimulation to ultrasound.

The sheer range of these approaches makes it pretty clear that the electroceutical’s final form is still an open research question. Macefield says we still don’t know the nitty-gritty of how vagus nerve stimulation works.

However, Tracey thinks the variety of approaches being developed doesn’t contravene the merits of the basic idea. How tech companies will make this work in the clinic, he says, is a separate business and IP question: “Can you do it with focused ultrasound? Can you do it with a device implanted with abdominal surgery? Can you do it with a device implanted in the neck? Can you do it with a device implanted in the brain, even? All of these strategies are enabled by the idea of the inflammatory reflex.” Until clinical trial data is in, he says, there’s no point arguing about the best way to manipulate the mechanism—and if one approach fails to work, that is not a referendum on the validity of the inflammatory reflex.

After stepping down from SetPoint’s board to resume a purely consulting role in 2011, Tracey focused on his lab work at the Feinstein Institutes, which he directs, to deepen understanding of this pathway. The research there is wide-ranging. Several researchers under his remit are exploring a type of noninvasive, indirect manipulation called transcutaneous auricular vagus nerve stimulation, which stimulates the skin of the ear with a wearable device. Tracey says it’s a “malapropism” to call this approach vagus nerve stimulation. “It’s just an ear buzzer,” he says. It may stimulate a sensory branch of the vagus nerve, which may engage the inflammatory reflex. “But nobody knows,” he says. Nonetheless, several clinical trials are underway.

“These things take time,” Tracey says. “It is extremely difficult to invent and develop a completely revolutionary new thing in medicine. In the history of medicine, anything that was truly new and revolutionary takes between 20 and 40 years from the time it’s invented to the time it’s widely adopted.”

“As the discoverer of this pathway,” he says, “what I want to see is multiple therapies, helping millions of people.” This vision will hinge on bigger trials conducted over many more years. These tend to be about as hard for devices as they are for drugs. Many results that look compelling in early trials disappoint in later rounds—just as for drugs. It will be possible, says Ludwig, “for them to pass a short-duration FDA trial yet still really not be a major improvement over the drug solutions.” Even after FDA approval, should it come, yet more studies will be needed to determine whether the implants are subject to the same issues that plague drugs, including habituation.

This vision of electroceuticals seems to have placed about a billion eggs into the single basket of the peripheral nervous system. In some ways, this makes sense. After all, the received wisdom has it that these nervous signals are the only way to exert electrical control of the other cells in the body. Those other trillions—the skin cells, the immune cells, the stem cells—are beyond the reach of direct electrical intervention.

Except in the past 20 years it’s become abundantly clear that they are not.

Other cells speak electricity

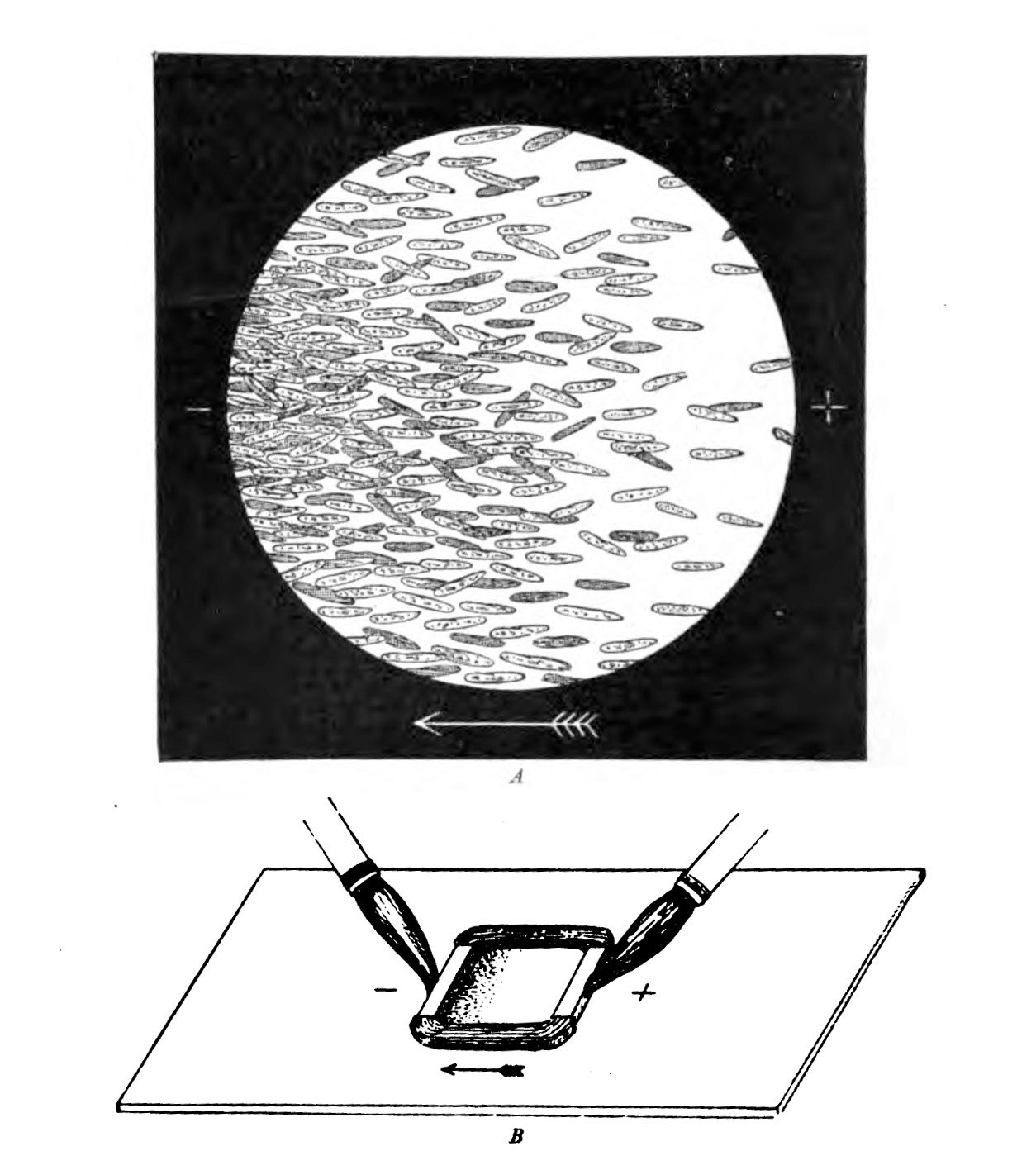

At the end of the 19th century, the German physiologist Max Verworn watched as a single-celled marine creature was drawn across the surface of his slide as if captured by a tractor beam. It had been, in a way: under the influence of an electric field, it squidged over to the cathode (the pole that attracts positive charge). Many other types of cells could be coaxed to obey the directional wiles of an electric field, a phenomenon known as galvanotaxis.

But this was too weird for biology, and charlatans already occupied too much of the space in the Venn diagram where electricity met medicine. (The association was formalized in 1910 in the Flexner Report, commissioned to improve the dismal state of American medical schools, which sent electrical medicine into exile along with the likes of homeopathy.) Everyone politely forgot about galvanotaxis until the 1970s and ’80s, when the peculiar behavior resurfaced. Yeast, fungi, bacteria, you name it—they all liked a cathode. “We were pulling every kind of cell along on petri dishes with an electric field,” says Ann Rajnicek of the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, who was among the first group of researchers who tried to discover the mechanism when scientific interest reawakened.

Galvanotaxis would have raised few eyebrows if the behavior had been confined to neurons. Those cells have evolved receptors that sense electric fields; they are a fundamental aspect of the mechanism the nervous system uses to send its information. Indeed, the reason neurons are so amenable to electrical manipulation in the first place is that electric implants hijack a relatively predictable mechanism. Zap a nerve or a muscle and you are forcing it to “speak” a language in which it is already fluent.

Non-excitable cells such as those found in skin and bone don’t share these receptors, but it keeps getting more obvious that they somehow still sense and respond to electric fields.

Why? We keep finding more reasons. Galvanotaxis, for example, is increasingly understood to play a crucial role in wound healing. In every species studied, injury to the skin produces an instant, internally generated electric field, and there’s overwhelming evidence that it guides patch-up cells to the center of the wound to start the rebuilding process. But galvanotaxis is not the only way these cells are led by electricity. During development, immature cells seem to sense the electric properties of their neighbors, which plays a role in their future identity—whether they become neurons, skin cells, fat cells, or bone cells.

Intriguing as this all was, no one had much luck turning such insights into medicine. Even attempts to go after the lowest-hanging fruit—by exploiting galvanotaxis for novel bandages—were for many years at best hit or miss. “When we’ve come upon wounds that are intractable, resistant, and will not heal, and we apply an electric field, only 50% or so of the cases actually show any effect,” says Anthony Guiseppi-Elie, a senior fellow with the American International Institute for Medical Sciences, Engineering, and Innovation.

However, in the past few years, researchers have found ways to make electrical stimulation outside the nervous system less of a coin toss.

That’s down to steady progress in our understanding of how exactly non-neural cells pick up on electric fields, which has helped calm anxieties around the mysticism and the Frankenstein associations that have attended biological responses to electricity.

The first big win came in 2006, with the identification of specific genes in skin cells that get turned on and off by electric fields. When skin is injured, the body’s native electric field orients cells toward the center of the wound, and the physiologist Min Zhao and his colleagues found important signaling pathways that are turned on by this field and mobilized to move cells toward this natural cathode. He also found associated receptors, and other scientists added to the catalogue of changes to genes and gene regulatory networks that get switched on and off under an electric field.

What has become clear since then is that there is no simple mechanism waiting at the end of the rainbow. “There isn’t one single master protein, as far as anybody knows, that regulates responses [to an electric field],” says Daniel Cohen, a bioengineer at Princeton University. “Every cell type has a different cocktail of stuff sticking out of it.”

But recent years have brought good news, in both experimental and applied science. First, the experimental platforms to investigate gene expression are in the middle of a transformation. One advance was unveiled last year by Sara Abasi, Guiseppi-Elie, and their colleagues at Texas A&M and the Houston Methodist Research Institute: their carefully designed research platform kept track of pertinent cellular gene expression profiles and how they change under electric fields—specifically, ones tuned to closely mimic what you find in biology. They found evidence for the activation of two proteins involved in tissue growth along with increased expression of a protein called CD-144, a specific version of what’s known as a cadherin. Cadherins are important physical structures that enable cells to stick to each other, acting like little handshakes between cells. They are crucial to the cells’ ability to act en masse instead of individually.

The other big improvement is in tools that can reveal just how cells work together in the presence of electric fields.

A different kind of electroceutical

A major limit on past experiments was that they tended to test the effects of electrical fields either on single cells or on whole animals. Neither is quite the right scale to offer useful insights, explains Cohen: measuring these dynamics in animals is too “messy,” but in single cells, the dynamics are too artificial to tell you much about how cells behave collectively as they heal a wound. That behavior emerges only at relevant scales, like bird flocks, schools of fish, or road traffic. “The math is identical to describe these types of collective dynamics,” he says.

In 2020, Cohen and his team came up with a solution: an experimental setup that strikes the balance between single cell (tells you next to nothing) and animal (tells you too many things at once). The device, called SCHEEPDOG, can reveal what is going on at the tissue level, which is the relevant scale for investigating wound healing.

It uses two sets of electrodes—a bit the way you might twiddle the dials on an Etch A Sketch—placed in a closed bioreactor, which better approximates how electric fields operate in biology. With this setup, Cohen and his colleagues can precisely tune the electrical environment of tens of thousands of cells at a time to influence their behavior.

Their subsequent “healing-on-a-chip” platform yielded an interesting discovery: skin cells’ response to an electric field depends on their maturity. The less mature, the easier they were to control.

The culprit? Those cadherins that Abasi and Guiseppi-Elie had also observed changing under electric fields. In mature cells, these little handshakes had become so strong that a competing electric field, instead of gently guiding the cells, caused them to rip apart. The immature skin cells followed the electric field’s directions without complaint.

After they found a way to dial down the cadherins with an antibody drug, all the cells synchronized. For Cohen, the lesson was that it’s more important to look at the system, and the collective dynamics that govern a behavior like wound healing, than at what is happening in any single cell. “This is really important because many clinical attempts at using electrical stimulation to accelerate wound healing have failed,” says Guiseppi-Elie, and it had never become clear why some worked and others some didn’t.

Cohen’s team is now working to translate these findings into next-generation bioelectric plasters. They are far from alone, and the payoff is more than skin deep. A lot of work is going on, some of it open and some behind closed doors with patents being closely guarded, says Cohen.

At Stanford, the University of Arizona, and Northwestern, researchers are creating smart electric bandages that can be implanted under the skin. They can also monitor the state of the wound in real time, increasing the stimulation if healing is too slow. More challenging, says Rajnicek, are ways to interface with less accessible areas of the body. However, here too new tools are revealing intriguing creative solutions.

Electric fields don’t have to directly change cells’ gene expression to be useful. There is another way their application can be turned to medical benefit. Electric fields evoke reactive oxygen species (ROS) in biological cells. Normally, these charged molecules are a by-product of a cell’s everyday metabolic activities. If you induce them purposefully using an external DC current, however, they can be hijacked to do your bidding.

Starting in 2020, the Swiss bioengineer Martin Fussenegger and an international team of collaborators began to publish investigations into this mechanism to power gene expression. He and his team engineered human kidney cells to be hypersensitive to the induced ROSs in quantities that normal cells couldn’t sense. But when these were generated by DC electrodes, the kidney cells could sense the minute quantities just fine.

Using this instrument, in 2023 they were able to create a tiny, wearable insulin factory. The designer kidney cells were created with a synthetic promoter—an engineered sequence of DNA that can drive expression of a target gene—that reacted to those faint induced ROSs by activating a cascade of genetic changes that opened a tap for insulin production on demand.

Then they packaged this electrogenetic contraption into a wearable device that worked for a month in a living mouse, which had been engineered to be diabetic (Fussenegger says that “others have shown that implanted designer cells can generally be active for over a year”). The designer cells in the wearable are kept alive by algae gelatine but are fed by the mouse’s own vascular system, permitting the exchange of nutrients and protein. The cells can’t get out, but the insulin they secrete can, seeping straight into the mouse’s bloodstream. Ten seconds a day of electrical stimulation delivered via needles connected to three AAA batteries was enough to make the implant perform like a pancreas, returning the mouse’s blood sugar to nondiabetic levels. Given how easy it would be to generalize the mechanism, Fussenegger says, there’s no reason insulin should be the only drug such a device can generate. He is quick to stress that this wearable device is very much in the proof-of-concept stage, but others outside the team are excited about its potential. It could provide a more direct electrical alternative to the solution electroceuticals promised for diabetes.

Escaping neurochauvinism

Before the concerted push around branding electroceuticals, efforts to tap the peripheral nervous system were fragmented and did not share much data. Today, thanks to SPARC, which is winding down, data-sharing resources have been centralized. And money, both direct and indirect, for the electroceuticals project has been lavish. Therapies—especially vagus nerve stimulation—have been the subject of “a steady increase in funding and interest,” says Imran Eba, a partner at GSK’s bioelectronics investment arm Action Potential Venture Capital. Eba estimates that the initial GSK seed of $50 million at Action Potential has grown to about $200 million in assets under management.

Whether you call it bioelectronic medicine or electroceuticals, some researchers would like to see the definition take on a broader remit. “It’s been an extremely neurocentric approach,” says Daniel Cohen.

Neurostimulation has not yet shown success against cancer. Other forms of electrical stimulation, however, have proved surprisingly effective. In one study on glioblastoma, tumor-treating fields offered an electrical version of chemotherapy: an electric field blasts a brain tumor, preferentially killing only cells whose electrical identity marks them as dividing (which cancer cells do, pathologically—but neurons, being fully differentiated, do not). A study recently published in The Lancet Oncology suggests that these fields could also work in lung cancer to boost existing drugs and extend survival.

All of this points to more sophisticated interventions than a zap to a nerve. “The complex things that we need to do in medicine will be about communicating with the collective decision-making and problem-solving of the cells,” says Michael Levin. He has been working to repurpose already-approved drugs so they can be used to target the electrical communication between cells. In a funny twist, he has taken to calling these drugs electroceuticals, which has ruffled some feathers. But he would certainly find support from researchers like Cohen. “I would describe electroceuticals much more broadly as anything that manipulates cellular electrophysiology,” Cohen says.

Even interventions with the nervous system could be helped by expanding our understanding of the ways nerve cells react to electricity beyond action potentials. Kim Gokoffski, a professor of clinical ophthalmology at the University of Southern California, is working with galvanotaxis as a possible means of repairing damage to the optic nerve. In prior experiments that involve regrowing axons—the cables that carry messages out of neurons—these new nerve fibers tend to miss the target they’re meant to rejoin. Existing approaches “are all pushing the gas pedal,” she says, “but no one is controlling the steering wheel.” So her group uses electric fields to guide the regenerating axons into position. In rodent trials, this has worked well enough to partially restore sight.

And yet, Cohen says, “there’s massive social stigma around this that is significantly hampering the entire field.” That stigma has dramatically shaped research direction and funding. For Gokoffski, it has led to difficulties with publishing. She also recounts hearing a senior NIH official refer to her lab’s work on reconnecting optic nerves as “New Age–y.” It was a nasty surprise: “New Age–y has a very bad connotation.”

However, there are signs of more support for work outside the neurocentric model of bioelectric medicine. The US Defense Department funds projects in electrical wound healing (including Gokoffski’s). Action Potential’s original remit—confined to targeting peripheral nerves with electrical stimulation—has expanded. “We have a broader approach now, where energy (in any form, be it electric, electromagnetic, or acoustic) can be directed to regulate neuronal or other cellular activities in the body,” Eba wrote in an email. Three of the companies now in their portfolio focus on areas outside neurostimulation. “While we don’t have any investments targeting wound healing or regenerative medicine specifically, there is no explicit exclusion here for us,” he says.

This suggests that the “social stigma” Cohen described around electrical medicine outside the nervous system is slowly beginning to abate. But if such projects are to really flourish, the field needs to be supported, not just tolerated—perhaps with its own road map and dedicated NIH program. Whether or not bioelectric medicine ends up following anything like the original electroceuticals road map, SPARC ensured a flourishing research community, one that is in hot pursuit of promising alternatives.

The use of electricity outside the nervous system needs a SPARC program of its own. But if history is any guide, first it needs a catchy name. It can’t be “electroceuticals.” And the researchers should definitely check the trademark listings before rolling it out.

Sally Adee is a science and technology writer and the author of We Are Electric: Inside the 200-Year Hunt for Our Body’s Bioelectric Code, and What the Future Holds.

This article has been updated to correct the name of the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research.