Four things you need to know about China’s AI talent pool

This story first appeared in China Report, MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

In 2019, MIT Technology Review covered a report that shined a light on how fast China’s AI talent pool was growing. Its main finding was pretty interesting: the number of elite AI scholars with Chinese origins had multiplied by 10 in the previous decade, but relatively few of them stayed in China for their work. The majority moved to the US.

Now the think tank behind the report has published an updated analysis, showing how the makeup of global AI talent has changed since—during a critical period when the industry has shifted significantly and become the hottest technology sector.

The team at MacroPolo, the think tank of the Paulson Institute, an organization that focuses on US-China relations, studied the national origin, educational background, and current work affiliation of top researchers who gave presentations and had papers accepted at NeurIPS, a top academic conference on AI. Their analysis of the 2019 conference resulted in the first iteration of the Global AI Talent Tracker. They’ve analyzed the December 2022 NeurIPS conference for an update three years later.

I recommend you read the original report, which has a very well-designed infographic that shows the talent flow across countries. But to save you some time, I also talked to the authors and highlighted what I think are the most surprising or important takeaways from the new report. Here are the four main things you need to know about the global AI talent landscape today.

1. China has become an even more important country for training AI talent.

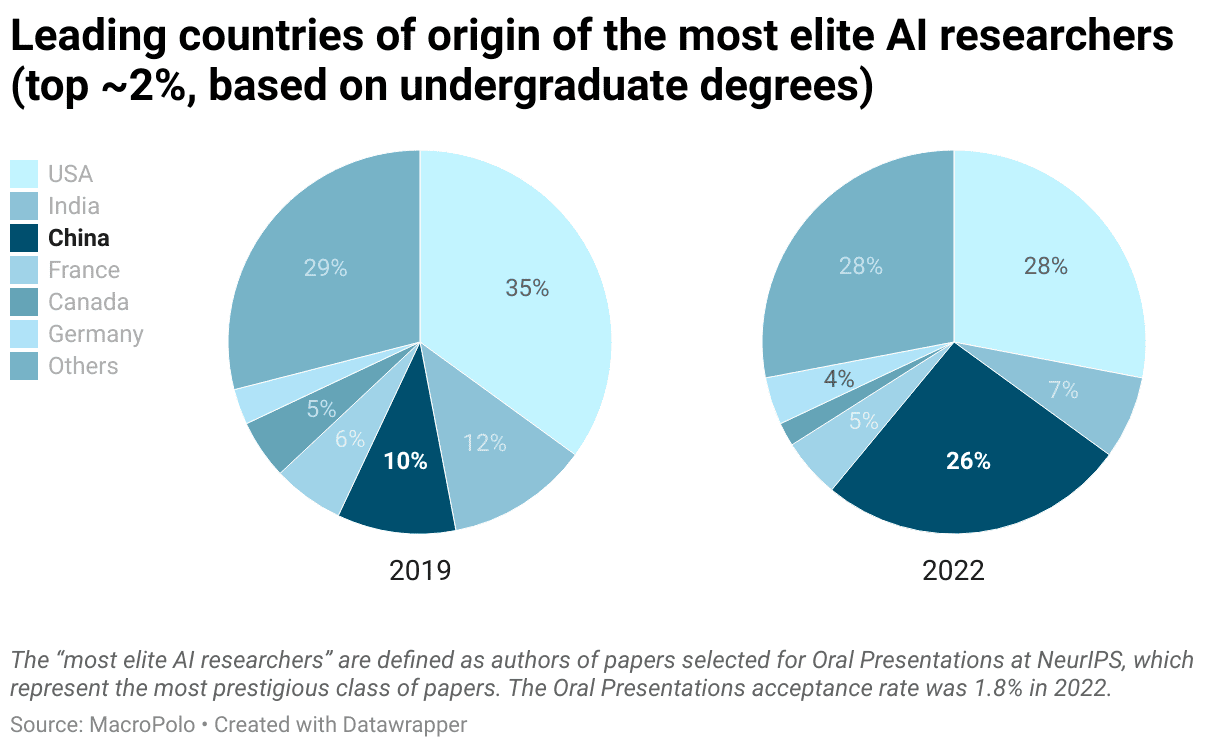

Even in 2019, Chinese researchers were already a significant part of the global AI community, making up one-tenth of the most elite AI researchers. In 2022, they accounted for 26%, almost dethroning the US (American researchers accounted for 28%).

“Timing matters,” says Ruihan Huang, senior research associate at MacroPolo and one of the lead authors. “The last three years have seen China dramatically expand AI programs across its university system—now there are some 2,000 AI majors—because it was also building an AI industry to absorb that talent.”

As a result of these university and industry efforts, many more students in computer science or other STEM majors have joined the AI industry, making Chinese researchers the backbone of cutting-edge AI research.

2. AI researchers now tend to stay in the country where they receive their graduate degree.

This is perhaps intuitive, but the numbers are still surprisingly high: 80% of AI researchers who went to a graduate school in the US stayed to work in the US, while 90% of their peers who went to a graduate school in China stayed in China.

In a world where major countries are competing with each other to take the lead in AI development, this finding suggests a trick they could use to expand their research capacity: invest in graduate-level institutions and attract overseas students to come.

This is particularly important in the US-China context, where the souring of the relationship between the two countries has affected the academic field. According to news reports, quite a few Chinese graduate students have been interrogated at the US border or even denied entry in recent years, as a Trump-era policy persisted. Along with the border restrictions imposed during the pandemic years, this hostility could have prevented more Chinese AI experts from coming to the US to learn and work.

3. The US still overwhelmingly attracts the most AI talent, but China is catching up.

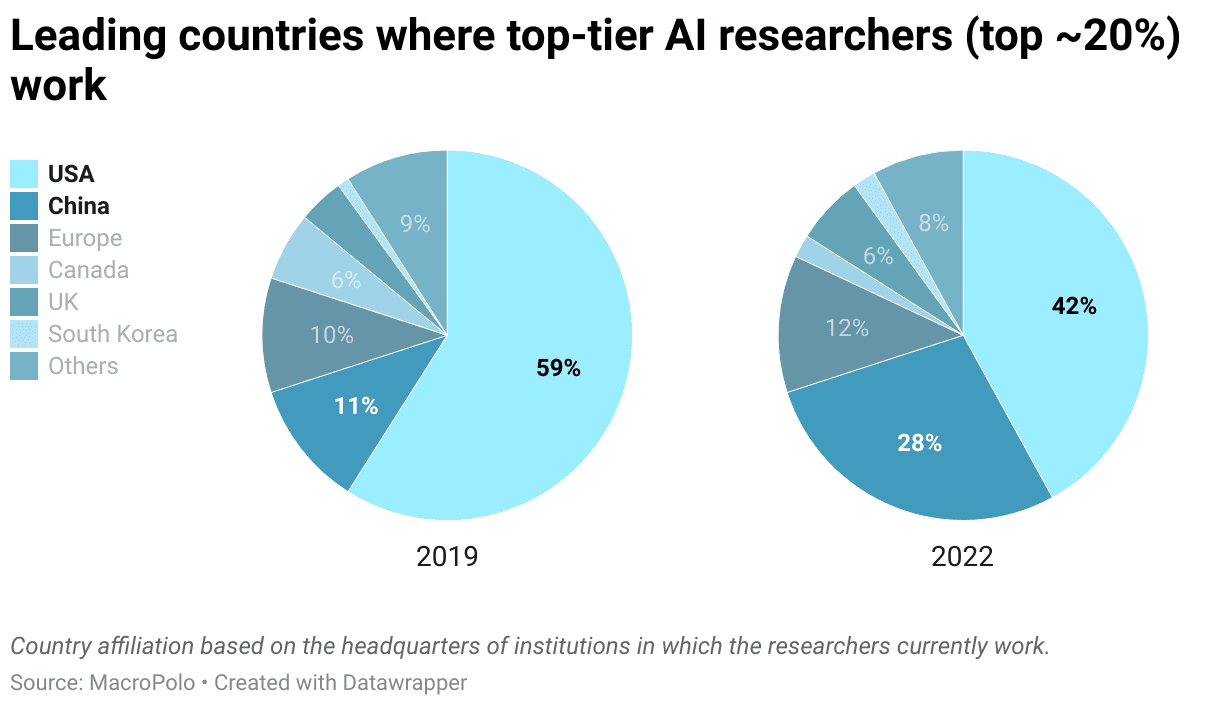

In both 2019 and 2022, the United States topped the rankings in terms of where elite AI researchers work. But it’s also clear that the distance between the US and other countries, particularly China, has shortened. In 2019, almost three-fifths of top AI researchers worked in the US; only two-fifths worked here in 2022.

“The thing about elite talent is that they generally want to work at the most cutting-edge and dynamic places. They want to do incredible work and be rewarded for it,” says AJ Cortese, a senior research associate at MacroPolo and another of the main authors. “So far, the United States still leads the way in having that AI ecosystem—from leading institutions to companies—that appeals to top talent.”

In 2022, 28% of the top AI researchers were working in China. This significant portion speaks to the growth of the domestic AI sector in China and the job opportunities it has created. Compared with 2019, three more Chinese universities and one company (Huawei) made it into the top tier of institutions that produce AI research.

It’s true that most Chinese AI companies are still considered to lag behind their US peers—for example, China usually trails the US by a few months in releasing comparable generative AI models. However, it seems like they have started catching up.

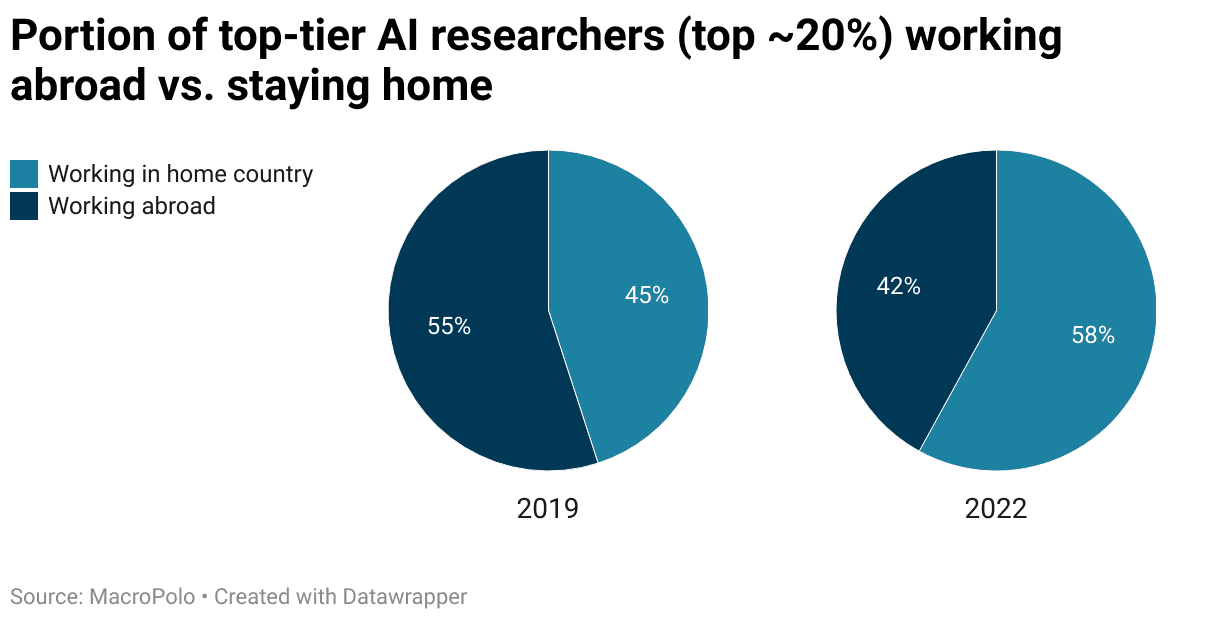

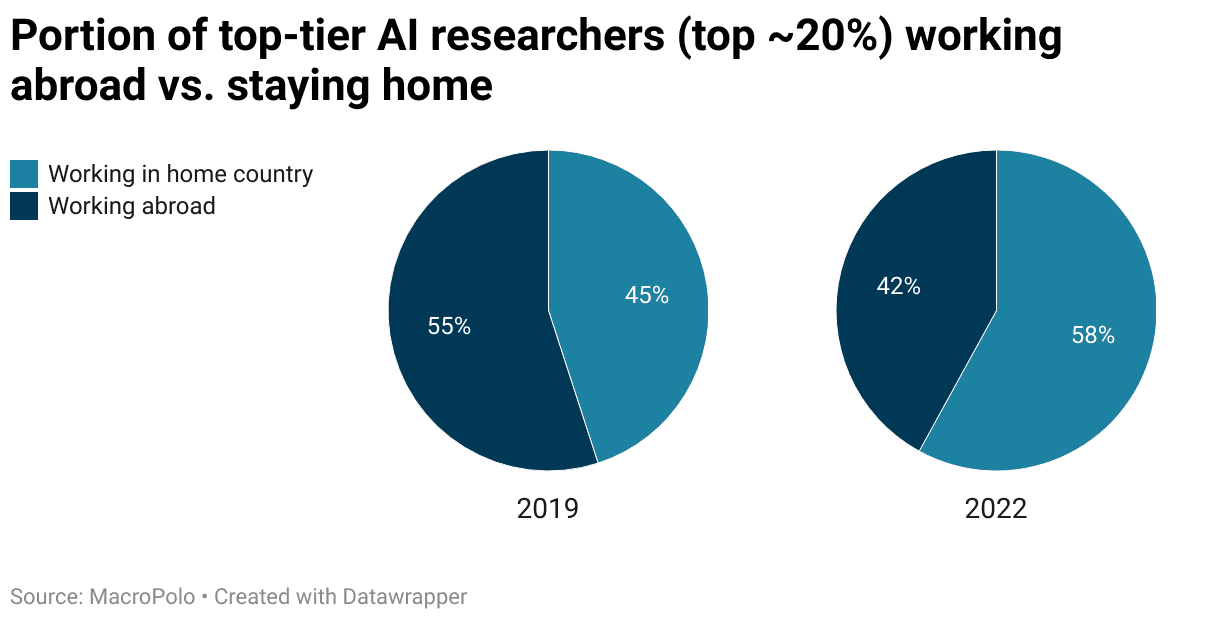

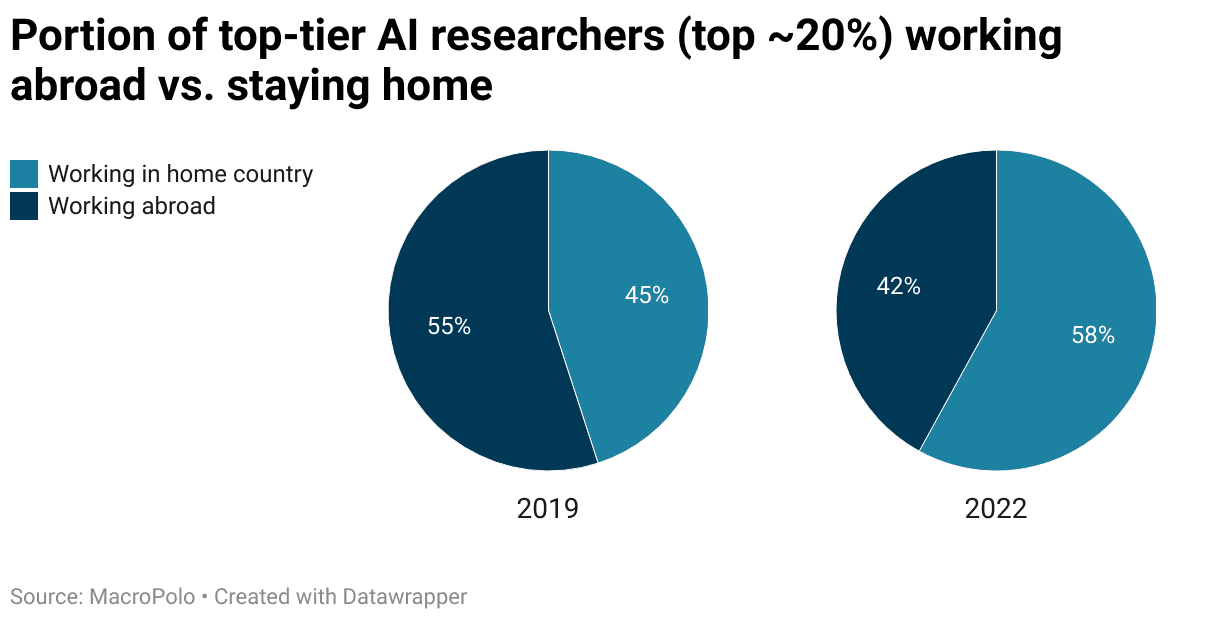

4. Top-tier AI researchers now are more willing to work in their home countries.

This is perhaps the biggest and also most surprising change in the data, in my opinion. Like their Chinese peers, more Indian AI researchers ended up staying in their home country for work.

In fact, this seems to be a broader pattern across the board: it used to be that more than half of AI researchers worked in a country different from their home. Now, the balance has tipped in favor of working in their own countries.

This is good news for countries trying to catch up with the US research lead in AI. “It goes without saying most countries would prefer ‘brain gain’ over ‘brain drain’—especially when it comes to a highly complex and technical discipline like AI,” Cortese says.

It’s not easy to create an environment and culture that not only retains its own talents but manages to pull scholars from other countries, but lots of countries are now working on it. I can only begin to imagine what the report might look like in a few years.

Did anything else stand out to you in the report? Let me know your thoughts by writing to zeyi@technologyreview.com.

Now read the rest of China Report

Catch up with China

1. The Dutch prime minister will visit China this week to discuss with Chinese president Xi Jinping whether the Dutch chipmaking equipment company ASML can keep servicing Chinese clients. (Reuters $)

- Here’s an inside look into ASML’s factory and how it managed to dominate advanced chipmaking. (MIT Technology Review)

2. Hong Kong passed a tough national security law that makes it more dangerous to protest Beijing’s rule. (BBC)

3. A new bill in France suggests imposing hefty fines on Shein and similar ultrafast-fashion companies for their negative environmental impact—as much as $11 per item that they sell in France. (Nikkei Asia)

4. Huawei filed a patent to make more advanced chips with a low-tech workaround. (Bloomberg $)

- Meanwhile, a US official accused the Chinese chip foundry SMIC of breaking US law by making a chip for Huawei. (South China Morning Post $)

5. Instead of the usual six and a half days a week, Tesla has instructed its Shanghai factory to reduce production to five days a week. The slowdown of EV sales in China could be the reason. (Bloomberg $)

6. TikTok is still having plenty of troubles. A new political TV ad (paid for by a mysterious new nonprofit), playing in three US swing states, attacks Zhang Fuping, a ByteDance vice president that very few people have heard of. (Punchbowl News)

- As TikTok still hasn’t reached a licensing deal with Universal Music Group, users have had to get creative to find alternative soundtracks for their videos. (Billboard)

7. China launched a communications satellite that will help relay signals for missions to explore the dark side of the moon. (Reuters $)

Lost in translation

The most-hyped generative AI app in China these days is Kimi, according to the Chinese publication Sina Tech. Released by Moonshot AI, a Chinese “unicorn” startup, Kimi made headlines last week when it announced it had started supporting inputting text using over 2 million Chinese characters. (For comparison, OpenAI’s GPT-4 Turbo currently supports inputting 100,000 Chinese characters, while Claude3-200K supports about 160,000 characters.)

While some of the app’s virality can be credited to a marketing push that intensified recently. Chinese users are now busy feeding popular and classic books to the model and testing how well it can understand the context. Feeling threatened, other Chinese AI apps owned by tech giants like Baidu and Alibaba have followed suit, announcing that they will soon support 5 million or even 10 million Chinese characters. But processing large amounts of text, while impressive, is very costly in the generative AI age—and some observers worry this isn’t the commercial direction that companies ought to head in.

One more thing

Fluffy pajamas, sweatpants, outdated attire: young Chinese people are dressing themselves in “gross outfits” to work—an intentional provocation to their bosses and an expression of silent resistance to the trend that glorifies career hustle. “I just don’t think it’s worth spending money to dress up for work, since I’m just sitting there,” one of them told the New York Times.

Update: The story has been updated to clarify the affiliation of the report authors.