How one mine could unlock billions in EV subsidies

A collection of brown pipes emerge at odd angles from the mud and overgrown grasses on a pine farm north of the tiny town of Tamarack, Minnesota.

Beneath these capped drill holes, Talon Metals has uncovered one of America’s densest nickel deposits—and now it wants to begin tunneling deep into the rock to extract hundreds of thousands of metric tons of mineral-rich ore a year.

If regulators approve the mine, it could mark the starting point in what this mining exploration company claims would become the country’s first complete domestic nickel supply chain, running from the bedrock beneath the Minnesota earth to the batteries in electric vehicles across the nation.

This is the second story in a two-part series exploring the hopes and fears surrounding a single mining proposal in a tiny Minnesota town. You can read the first part here.

The US government is poised to provide generous support at every step, distributing millions to billions of dollars in subsidies for those refining the metal, manufacturing the batteries, and buying the cars and trucks they power.

The products generated with the raw nickel that would flow from this one mining project could theoretically net more than $26 billion in subsidies, just through federal tax credits created by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). That’s according to an original analysis by Bentley Allan, an associate professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University and co-director of the Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab, produced in coordination with MIT Technology Review.

One of the largest beneficiaries would be battery manufacturers that use Talon’s nickel, which could secure more than $8 billion in tax credits. About half of that could go to the EV giant Tesla, which has already agreed to purchase tens of thousands of metric tons of the metal from this mine.

But the biggest winner, at least collectively, would be American consumers who buy EVs powered by those batteries. All told, they could enjoy nearly $18 billion in savings.

While it’s been widely reported that the IRA could unleash at least hundreds of billions of federal dollars, MIT Technology Review wanted to provide a clearer sense of the law’s on-the-ground impact by zeroing in on a single project and examining how these rich subsidies could be unlocked at each point along the supply chain. (Read my related story on Talon’s proposal and the community reaction to it here.)

We consulted with Allan to figure out just how much money is potentially in play, where it’s likely to go, and what it may mean for emerging industries and the broader economy.

These calculations are all high-end estimates meant to assess the full potential of the act, and they assume that every company and customer qualifies for every tax credit available at each point along the supply chain. In the end, the government almost certainly won’t hand out the full amounts that Allan calculated, given the varied and complex restrictions in the IRA and other factors.

In addition, Talon itself may not obtain any subsidies directly through the law, according to recent but not-yet-final IRS interpretations. But thanks to rich EV incentives that will stimulate demand for domestic critical minerals, the company still stands to benefit indirectly from the IRA.

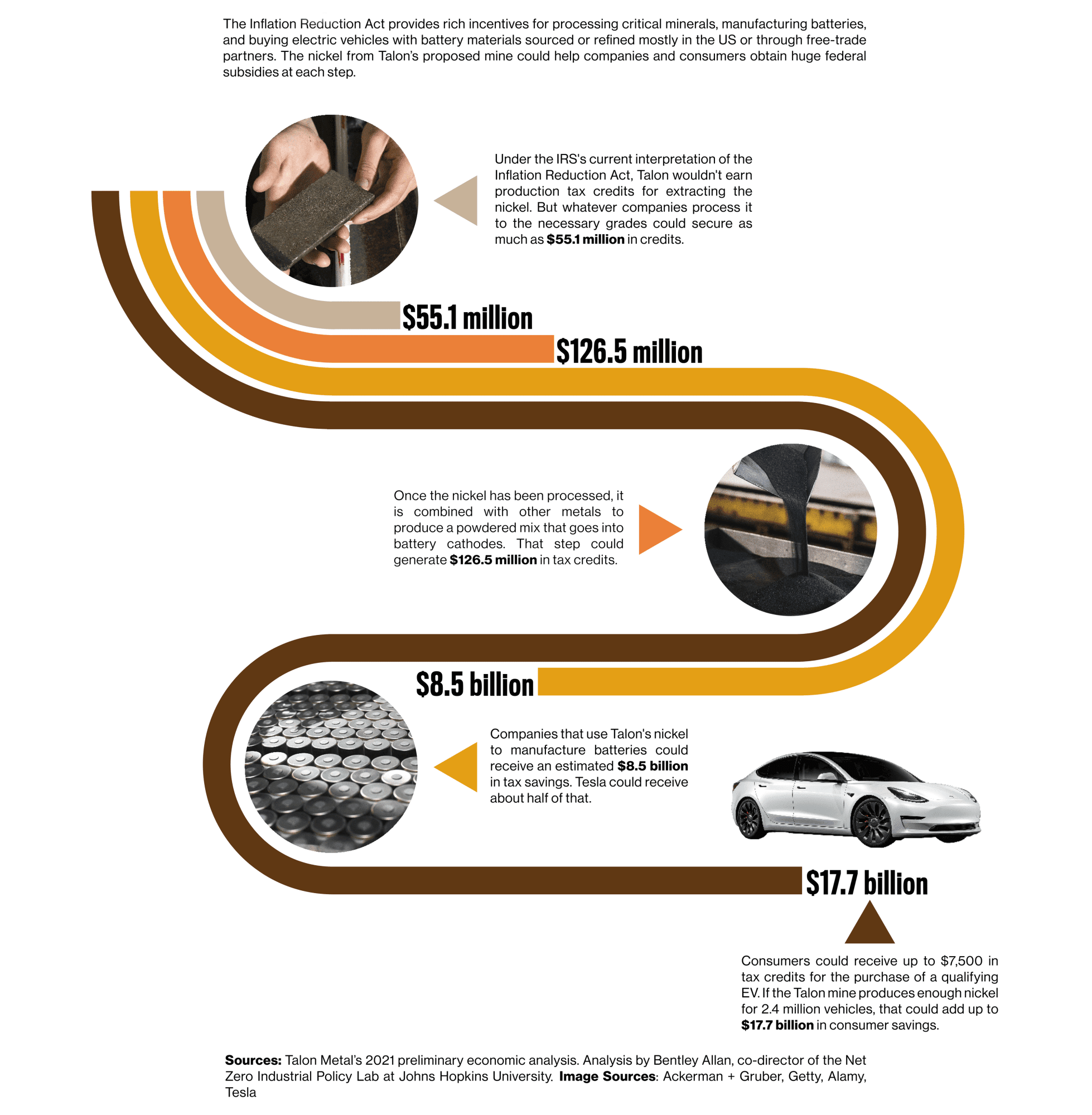

How $26 billion in tax credits could break down across a new US nickel supply chain

The sheer scale of the numbers offer a glimpse into how and why the IRA, signed into law in August 2022, has already begun to drive projects, reconfigure sourcing arrangements, and accelerate the shift away from fossil fuels.

Indeed, the policies have dramatically altered the math for corporations considering whether, where, and when to build new facilities and factories, helping to spur at least tens of billions of dollars’ worth of private investments into the nation’s critical-mineral-to-EV supply chain, according to several analyses.

“If you try to work out the math on these for five minutes, you start to be really shocked by what you see on paper,” Allan says, noting that the IRA’s incentives ensure that many more projects could be profitably and competitively developed in the US. “It’s going to transform the country in a serious way.”

An urgent game of catch-up

For decades, the US steadily offshored the messy business of mining and processing metals, leaving other nations to deal with the environmental damage and community conflicts that these industries often cause. But the country is increasingly eager to revitalize these sectors as climate change and simmering trade tensions with China raise the economic, environmental, and geopolitical stakes.

Critical minerals like lithium, cobalt, nickel, and copper are the engine of the emerging clean-energy economy, essential for producing solar panels, wind turbines, batteries, and EVs. Yet China dominates production of the source materials, components, and finished goods for most of these products, following decades of strategic government investments and targeted trade policies. It refines 71% of the type of nickel used for batteries and produces more than 85% of the world’s battery cells, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

The US is now in a high-stakes scramble to catch up and ensure its unfettered access to these materials, either by boosting domestic production or by locking in supply chains through friendly trading partners. The IRA is the nation’s biggest bet, by far, on bolstering these industries and countering China’s dominance over global cleantech supply chains. By some estimates, it could unlock more than $1 trillion in federal incentives.

“It should be sufficient to drive transformational progress in clean-energy adoption in the United States,” says Kimberly Clausing, a professor at the UCLA School of Law who previously served as deputy assistant secretary for tax analysis at the Treasury Department. “The best modeling seems to show it will reduce emissions substantially, getting us halfway to our Paris Agreement goals.”

Among other subsidies, the IRA provides tax credits that companies can earn for producing critical minerals, electrode materials, and batteries, enabling them to substantially cut their federal tax obligations.

But the provisions that are really driving the rethinking of sourcing and supply chains are the so-called domestic content requirements contained in the tax credits for purchasing EVs. For consumers to earn the full credits, and for EV makers to benefit from the boost in demand they’ll generate, a significant share of the critical minerals the batteries contain must be produced in the US, sourced from free-trade partners, or recycled in North America, among other requirements.

This makes the critical minerals coming out of a mine like Talon’s especially valuable to US car companies since it could help ensure that their EV models and customers qualify for these credits.

Mining and refining

Nickel, like the deposits found in Minnesota, is of particular importance for cleaning up the auto sector. The metal boosts the amount of energy that can be packed into battery cathodes, extending the range of cars and making possible heavier electric vehicles, like trucks and even semis.

Global nickel demand could rise 112% by 2040, according to the International Energy Agency, owing primarily to an expected ninefold increase in demand for EV batteries. But there’s only one dedicated nickel mine operating in the US today, and most processing of the metal happens overseas.

In a preliminary economic analysis of the proposed mine released in 2021, Talon said it hoped to dig up nearly 11 million metric tons of ore over a nine-year period, including more than 140,000 tons of nickel. That’s enough to produce lithium-ion batteries that could power almost 2.4 million electric vehicles, Allan finds.

After Talon mines the ore, the company plans to ship the material more than 400 miles west by rail to a planned processing site in central North Dakota that would produce what’s known as “nickel in concentrate,” which is generally around 10% pure.

But that’s not enough to earn any subsidies under the current interpretation of the IRA’s tax credit for critical-mineral production. The law specifies that a company must convert nickel into a highly refined form known as “nickel sulphate” or process the metal to at least 99% purity by mass to be eligible for tax credits that cover 10% of the operating cost. Allan estimates that whichever company or companies carry out that step could earn subsidies that exceed $55 million.

From there, the nickel would still need to be processed and mixed with other metals to produce the “cathode active materials” that go into a battery. Whatever companies carry out that step could secure some share of another $126.5 million in tax savings, thanks to a separate credit covering 10% of the costs of generating these materials, Allan notes.

Some share of the subsidies from these two tax credits might go to Tesla, which has stressed that it’s bringing more aspects of battery manufacturing in-house. For instance, it’s in the process of constructing its own lithium refinery and cathode plant in Texas.

But it’s not yet clear what other companies could be involved in processing the nickel mined by Talon and, thus, who would benefit from these particular provisions.

Talon and other mining companies have campaigned to have the costs for mining raw materials included in the critical-mineral production tax credit, but the IRS recently stated in a proposed rule that this step won’t qualify.

Todd Malan, Talon’s chief external affairs officer and head of climate strategy, argues that this and other recent determinations will limit the incentives for companies to develop new mines in the US, or to make sure that any mines that are developed meet the higher environmental and labor standards the Biden administration and others have been calling for.

(The determinations could change since the Treasury Department and IRS have said they are still considering including the costs of mining in the tax credits. They have requested additional comments on the matter.)

Even if Talon doesn’t obtain any IRA subsidies, it still stands to earn federal funds in several other ways. The company is set to receive a nearly $115 million grant from the Department of Energy to build the North Dakota processing site, through funds freed up under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. In addition, in September Talon secured nearly $21 million in matching grants through the Defense Production Act, which will support further nickel exploration in Minnesota and at another site the company is evaluating in Michigan. (These numbers are not included in Allan’s overall $26 billion estimate.)

Talon Metals could receive $136 million in federal subsidies

The math

Allan says that his findings are best thought of as ballpark figures. Some of Talon’s estimates have already changed, and the actual mineral quantities and operating costs will depend on a variety of factors, including how the company’s plans shift, what state and local regulators ultimately approve, what Talon actually pulls out of the ground, how much nickel the ore contains, and how much costs shift throughout the supply chain in the coming years.

His analysis assumes a preparation cost of $6.68 per kilowatt-hour for cathode active materials, based on an earlier analysis in the journal Energies. It did not evaluate any potential subsidies associated with other metals that Talon may extract from the mine, such as iron, copper, and cobalt. Please see his full research brief on the Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab site.

Companies can use the IRA tax credits to reduce or even eliminate their federal tax obligations, both now and in tax years to come. In addition, businesses can transfer and sell the tax credits to other taxpayers.

Most of the tax credits in the IRA begin to phase out in 2030, so companies need to move fast to take advantage of them. The subsidies for critical-mineral production, however, don’t have any such cutoff.

Where will the money go and what will it do?

The $136 million in direct federal grants would double Talon’s funds for exploratory drilling efforts and cover about 27% of the development cost for its North Dakota processing plant.

The company says that these projects will help accelerate the country’s shift toward EVs and reduce the nation’s reliance on China for critical minerals. Further, Talon notes the mine will provide significant local economic benefits, including about 300 new jobs. That’s in addition to the nearly 100 employees already working in or near Tamarack. The company also expects the operation to generate nearly $110 million in mineral royalties and taxes paid to the state, local government, and the regional school district.

Plenty of citizens around Tamarack, however, argue that any economic benefits will come with steep trade-offs in terms of environmental and community impacts. A number of local tribal members fear the project could contaminate waterways and harm the region’s plants and animals.

“The energy transition cannot be built by desecrating native lands,” said Leanna Goose, a member of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe, in an email. “If these ‘critical’ minerals leave the ground and are taken out from on or near our reservations, our people would be left with polluted water and land.”

Meanwhile, as it becomes clear just how much federal money is at stake, opposition to the IRA and other climate-related laws is hardening. Congressional Republicans, some of whom have portrayed the tax subsidies as corporate handouts to the “wealthy and well connected,” have repeatedly attempted to repeal key provisions of the laws. In addition, some environmentalists and left-wing critics have chided the government for offering generous subsidies to controversial companies and projects, including Talon’s.

Talon stresses that it has made significant efforts to limit pollution and address Indigenous concerns. In addition, Malan pushed back on Allan’s findings. He says the overall estimate of $26 billion in subsidies across the supply chain significantly exaggerates the likely outcome, given numerous ways that companies and consumers might fail to qualify for the tax credits.

“I think it’s too much to tie it back to a little mining company in Minnesota,” he says.

He emphasizes that Talon will earn money only for selling the metal it extracts, and that it will receive other federal grants only if it secures permits to proceed on its projects. (The company could also apply to receive separate IRA tax credits that cover a portion of the investments made into certain types of energy projects, but it has not at this time.)

Boosting the battery sector

The next stop in the supply chain is the battery makers.

The amount of nickel that Talon expects to pull from the mine could be used to produce cathodes for nearly 190 million kilowatt-hours’ worth of lithium-ion batteries, according to Allan’s findings.

Manufacturing that many batteries could generate some $8.5 billion from a pair of IRA tax credits worth $45 per kilowatt-hour, dwarfing the potential subsidies for processing the nickel.

Any number of companies might purchase metals from Talon to build batteries, but Tesla has already agreed to buy 75,000 tons of nickel in concentrate from the North Dakota facility. (The companies have not disclosed the financial terms of the deal.)

Given the batteries that could be produced with this amount of metal, Tesla’s share of these tax savings could exceed $4 billion, Allan found.

The tax credits add up to “a third of the cost of the battery, full stop,” he says. “These are big numbers. The entire cost of building the plant, at least, is covered by the IRA.”

What Talon’s nickel may mean for Tesla

The math

The subsidies for battery makers would flow from two credits within the IRA. Those include a $35-per-kilowatt-hour tax credit for manufacturing battery cells and a $10-per-kilowatt-hour credit for producing battery modules, which are the bundles of interoperating cells that slot into vehicles. Allan’s calculations assume that all the metal will be used to produce nickel-rich NMC 811 batteries, and that every EV will include an 80-kilowatt-hour battery pack that costs $153 per kilowatt-hour to produce.

Where will the money go and what will it do?

Those billions are just what Tesla could secure in tax credits from the nickel it buys from Talon. It and other battery makers could qualify for still more government subsidies for batteries produced with critical minerals from other sources.

Tesla didn’t respond to inquiries from MIT Technology Review. But its executives have said they believe Tesla’s batteries will qualify for the manufacturing tax credits, even before Talon’s mining and processing plants are up and running.

On an earnings call last January, Zachary Kirkhorn, who was then the company’s chief financial officer, said that Tesla expected the battery subsidies from its current production lines to total $150 million to $250 million per quarter in 2023. He said the company intends to use the tax credits to lower prices and promote greater adoption of electric vehicles: “We want to use this to accelerate sustainable energy, which is our mission and also the goal of [the IRA].”

But these potential subsidies are clear evidence that the US government is dedicating funds to the wrong societal priorities, says Jenna Yeakle, an organizer for the Sierra Club North Star Chapter in Minnesota, which added its name to a letter to the White House criticizing federal support for Talon’s proposals.

“People are struggling to pay rent and put food on the table and to navigate our monopolized corporate health-care system,” she says. “Do we need to be subsidizing Elon Musk’s bank account?”

Still, the IRA’s tax credits will go to numerous battery companies beyond Tesla.

In fact, the incentives are already reshaping the marketplace, driving a sharp increase in the number of battery and electric-vehicle projects announced, according to the EV Supply Chain Dashboard, a database managed by Jay Turner, a professor of environmental studies at Wellesley College and author of Charged: A History of Batteries and Lessons for a Clean Energy Future.

As of press time, 81 battery and EV-related projects representing $79 billion in investments and more than 50,000 jobs have been announced across the US since Biden signed the IRA. On an annual basis, that’s nearly three times the average dollar figures announced in recent years before the law was enacted. The projects include BMW, Hyundai, and Ford battery plants, Tesla’s semi manufacturing pilot plant in Nevada, and Redwoods Materials’ battery recycling facility in South Carolina.

“It’s really exceptional,” Turner says. “I don’t think anybody expected to see so many battery projects, so many jobs, and so many investments over the past year.”

Driving EV sales

The biggest subsidy, though also the most diffuse one, would go to American consumers.

The IRA offers two tax credits worth up to $7,500 combined for purchasing EVs and plug-in hybrids if the battery materials and components comply with the domestic content requirements.

Since the nickel that Talon expects to extract from the Minnesota mine could power nearly 2.4 million electric vehicles, consumers could collectively see $17.7 billion in potential savings if all those vehicles qualify for both credits, Allan finds.

Talon’s Malan says this estimate significantly overstates the likely consumer savings, noting that many purchases won’t qualify. Indeed, an individual with a gross income that exceeds $150,000 won’t be eligible, nor will pickups, vans, and SUVs that cost more than $80,000. That would rule out, for instance, the high-end model of Tesla’s Cybertruck.

A number of Tesla models are currently excluded from one or both consumer credits, for varied and confusing reasons. But the Talon deal and other recent sourcing arrangements, as well as the company’s plans to manufacture more of its own batteries, could help more of Tesla’s vehicles to qualify in the coming months or years.

The IRA’s consumer incentives are likely to do more to stimulate demand than previous federal EV policies, in large part because customers can take them in the form of a price cut at the point of sale, says Gil Tal, director of the Electric Vehicle Research Center at the University of California, Davis. Previously, such incentives would simply reduce the buyer’s federal obligations come tax season.

RMI, a nonprofit research group focused on clean energy, projects that all the EV provisions within the IRA, which also include subsidies for new charging stations, will spur the sales of an additional 37 million electric cars and trucks by 2032. That would propel EV sales to around 80% of new passenger-automobile purchases. Those vehicles, in turn, could eliminate 2.4 billion tons of transportation emissions by 2040.

The math

The IRA offers two tax credits that could apply to EV buyers. The first is a $3,750 credit for those who purchase vehicles with batteries that contain a significant portion of critical minerals that were mined or processed in the US, or in a country with which the US has a free-trade agreement. The required share is 50% in 2024 but reaches 80% beginning in 2027. Cars and trucks may also qualify if the materials came from recycling in North America.

Buyers can also earn a separate $3,750 credit if a specified share of the battery components in the vehicle were manufactured or assembled in North America. The share is 60% this year and next but reaches 100% in 2029.

The big bet

There are lingering questions about how many of the projects sparked by the country’s new green industrial policies will ultimately be built—and what the US will get for all the money it’s giving up.

After all, the tens of billions of dollars’ worth of tax credits that could be granted throughout the Talon-to-Tesla-to-consumer nickel supply chain is money that isn’t going to the federal government, and isn’t funding services for American taxpayers.

The IRA’s impacts on tax coffers are certain to come under greater scrutiny as the programs ramp up, the dollar figures rise, projects run into trouble, and the companies or executives benefiting engage in questionable practices. After all, that’s exactly what happened in the aftermath of the country’s first major green industrial policy efforts a decade ago, when the high-profile failures of Solyndra, Fisker, and other government-backed clean-energy ventures fueled outrage among conservative critics.

Nevertheless, Tom Moerenhout, a research scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, insists it’s wrong to think of these tax credits as forgone federal revenue.

In many cases, the projects set to get subsidies for 10% of their operating costs would not otherwise have existed in the first place, since those processing plants and manufacturing facilities would have been built in other, cheaper countries. “They would simply go to China,” he says.

UCLA’s Clausing doesn’t entirely agree with that take, noting that some of this money will go to projects that would have happened anyway, and some of the resources will simply be pulled from other sectors of the economy or different project types.

“It doesn’t behoove us as experts to argue this is free money,” she says. “Resources really do have costs. Money doesn’t grow on trees.”

But any federal expenses here are “still cheaper than the social cost of carbon,” she adds, referring to the estimated costs from the damage associated with ongoing greenhouse-gas pollution. “And we should keep our eyes on the prize and remember that there are some social priorities worth paying for—and this is one of those.”

In the end, few expect the US’s sweeping climate laws to completely achieve any of the hopes underlying them on their own. They won’t propel the US to net-zero emissions. They won’t enable the country to close China’s massive lead in key minerals and cleantech, or fully break free from its reliance on the rival nation. Meanwhile, the battle to lock down access to critical minerals will only become increasingly competitive as more nations accelerate efforts to move away from fossil fuels—and it will generate even more controversy as communities push back against proposals over concerns about environmental destruction.

But the evidence is building that the IRA in particular is spurring real change, delivering at least some progress on most of the goals that drove its passage: galvanizing green-tech projects, cutting emissions, creating jobs, and moving the nation closer to its clean-energy future.

“It is catalyzing investment up and down the supply chain across North America,” Allan says. “It is a huge shot in the arm of American industry.”