Lately, everywhere I scroll, I keep seeing the same fish-eyed CCTV view: a grainy wide shot from the corner of a living room, a driveway at night, an empty grocery store. Then something impossible happens. JD Vance shows up at the doorstep in a crazy outfit. A car folds into itself like paper and drives away. A cat comes in and starts hanging out with capybaras and bears, as if in some weird modern fairy tale.

This fake-surveillance look has become one of the signature flavors of what people now call AI slop. For those of us who spend time online watching short videos, slop feels inescapable: a flood of repetitive, often nonsensical AI-generated clips that washes across TikTok, Instagram, and beyond. For that, you can thank new tools like OpenAI’s Sora (which exploded in popularity after launching in app form in September), Google’s Veo series, and AI models built by Runway. Now anyone can make videos, with just a few taps on a screen.

If I were to locate the moment slop broke through into popular consciousness, I’d pick the video of rabbits bouncing on a trampoline that went viral this summer. For many savvy internet users, myself included, it was the first time we were fooled by an AI video, and it ended up spawning a wave of almost identical riffs, with people making videos of all kinds of animals and objects bouncing on the same trampoline.

My first reaction was that, broadly speaking, all of this sucked. That’s become a familiar refrain, in think pieces and at dinner parties. Everything online is slop now—the internet “enshittified,” with AI taking much of the blame. Initially, I largely agreed, quickly scrolling past every AI video in a futile attempt to send a message to my algorithm. But then friends started sharing AI clips in group chats that were compellingly weird, or funny. Some even had a grain of brilliance buried in the nonsense. I had to admit I didn’t fully understand what I was rejecting—what I found so objectionable.

To try to get to the bottom of how I felt (and why), I recently spoke to the people making the videos, a company creating bespoke tools for creators, and experts who study how new media becomes culture. What I found convinced me that maybe generative AI will not end up ruining everything. Maybe we have been too quick to dismiss AI slop. Maybe there’s a case for looking beyond the surface and seeing a new kind of creativity—one we’re watching take shape in real time, with many of us actually playing a part.

The slop boom

“AI slop” can and does refer to text, audio, or images. But what’s really broken through this year is the flood of quick AI-generated video clips on social platforms, each produced by a short written prompt fed into an AI model. Under the hood, these models are trained on enormous data sets so they can predict what every subsequent frame should look or sound like. It’s much like the process by which text models produce answers in a chat, but slower and far more power-hungry.

Early text-to-video systems, released around 2022 to 2023, could manage only a few seconds of blurry motion; objects warped in and out of existence, characters teleported around, and the giveaway that it was AI was usually a mangled hand or a melting face. In the past two years, newer models like Sora2, Veo 3.1, and Runway’s latest Gen-4.5 have dramatically improved, creating realistic, seamless, and increasingly true-to-prompt videos that can last up to a minute. Some of these models even generate sound and video together, including ambient noise and rough dialogue.

These text-to-video models have often been pitched by AI companies as the future of cinema—tools for filmmakers, studios, and professional storytellers. The demos have leaned into widescreen shots and dramatic camera moves. OpenAI pitched Sora as a “world simulator” while courting Hollywood filmmakers with what it boasted were movie-quality shorts. Google introduced Veo 3 last year as a step toward storyboards and longer scenes, edging directly into film workflows.

All this hinged on the idea that people wanted to make AI-generated videos that looked real. But the reality of how they’re being used is more modest, weirder—and arguably much more interesting. What has turned out to be the home turf for AI video is the six-inch screen in our hands.

Anyone can and does use these tools; a report by Adobe released in October shows that 86% of creators are using generative AI. But so are average social media users—people who aren’t “creators” so much as just people with phones.

That’s how you end up with clips showing things like Indian prime minister Narendra Modi dancing with Gandhi, a crystal that melts into butter the moment a knife touches it, or Game of Thrones reimagined as Henan opera—videos that are hypnotic, occasionally funny, and often deeply stupid. And while micro-trends didn’t start with AI—TikTok and Reels already ran on fast-moving formats—it feels as if AI poured fuel on that fire. Perhaps because the barrier to copying an idea becomes so low, a viral video like the bunnies on trampoline can easily and quickly spawn endless variations on the same concept. You don’t need a costume or a filming location anymore; you just tweak the prompt, hit Generate, and share.

Big tech companies have also jumped on the idea of AI videos as a new social medium. The Sora app allows users to insert AI versions of themselves and other users into scenes. Meta’s Vibes app wants to turn your entire feed into nonstop AI clips.

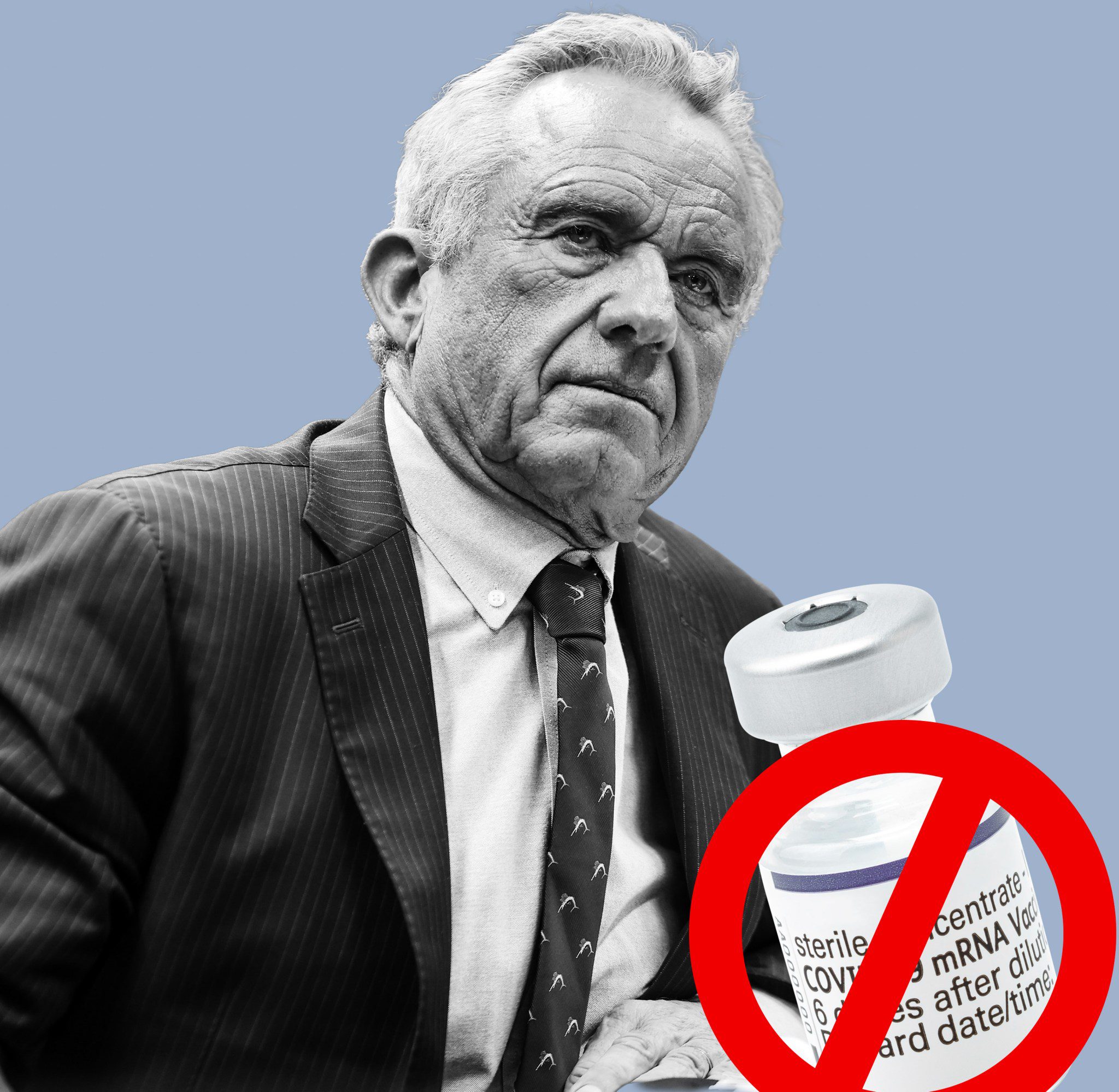

Of course, the same frictionless setup that allows for harmless, delightful creations also makes it easy to generate much darker slop. Sora has already been used to create so many racist deepfakes of Martin Luther King Jr. that the King estate pushed the company to block new MLK videos entirely. TikTok and X are seeing Sora-watermarked clips of women and girls being strangled circulating in bulk, posted by accounts seemingly dedicated to this one theme. And then there’s “nazislop,” the nickname for AI videos that repackage fascist aesthetics and memes into glossy, algorithm-ready content aimed at teens’ For You pages.

But the prevalence of bad actors hasn’t stopped short AI videos from flourishing as a form. New apps, Discord servers for AI creators, and tutorial channels keep multiplying. And increasingly, the energy in the community seems to be shifting away from trying to create stuff that “passes as real” toward embracing AI’s inherent weirdness. Every day, I stumble across creators who are stretching what “AI slop” is supposed to look like. I decided to talk to some of them.

Meet the creators

Like those fake surveillance videos, many popular viral AI videos rely on a surreal, otherworldly quality. As Wenhui Lim, an architecture designer turned full-time AI artist, tells me, “There is definitely a competition of ‘How weird we can push this?’ among AI video creators.”

It’s the kind of thing AI video tools seem to handle with ease: pushing physics past what a normal body can do or a normal camera can capture. This makes AI a surprisingly natural fit for satire, comedy skits, parody, and experimental video art—especially examples involving absurdism or even horror. Several popular AI creators that I spoke with eagerly tap into this capability.

Drake Garibay, a 39-year-old software developer from Redlands, California, was inspired by body-horror AI clips circulating on social media in early 2025. He started playing with ComfyUI, a generative media tool, and ended up spending hours each week making his own strange creations. His favorite subject is morbid human-animal hybrids. “I fell right into it,” he says. “I’ve always been pretty artistic, [but] when I saw what AI video tools can do, I was blown away.”

Since the start of this year, Garibay has been posting his experiments online. One that went viral on TikTok, captioned “Cooking up some fresh AI slop,” shows a group of people pouring gooey dough into a pot. The mixture suddenly sprouts a human face, which then emerges from the boiling pot with a head and body. It has racked up more than 8.3 million views.

AI video technology is evolving so quickly that even for creative professionals, there is a lot to experiment with. Daryl Anselmo, a creative director turned digital artist, has been experimenting with the technology since its early days, posting an AI-generated video every day since 2021. He tells me that uses a wide range of tools, including Kling, Luma, and Midjourney, and is constantly iterating. To him, testing the boundaries of these AI tools is sometimes itself the reward. “I would like to think there are impossible things that you could not do before that are still yet to be discovered. That is exciting to me,” he says.

Anselmo has collected his daily creations over the past four years into an art project, titled AI Slop, that has been exhibited in multiple galleries, including the Grand Palais Immersif in Paris. There’s obvious attention to mood and composition. Some clips feel like something closer to an art-house vignette than a throwaway meme. Over time, Anselmo’s project has taken a darker turn as his subjects shift from landscapes and interior design toward more of the body horror that drew Garibay in.

His breakout piece, feel the agi, shows a hyperrealistic bot peeling open its own skull. Another video he shared recently features a midnight diner populated by anthropomorphized Tater Tots, titled Tot and Bothered; with its vintage palette and slow, mystical soundtrack, the piece feels like a late-night fever dream.

One further benefit of these AI systems is that they make it easier for creators to build recurring spaces and casts of characters that function like informal franchises. Lim, for instance, is the creator of a popular AI video account called Niceaunties, inspired by the “auntie culture” in Singapore, where she’s from.

“The word ‘aunties’ often has a slightly negative connotation in Singaporean culture. They are portrayed as old-fashioned, naggy, and lacking boundaries. But they are also so resourceful, funny, and at ease with themselves,” she says. “I want to create a world where it’s different for them.”

Her cheeky, playful videos show elderly Asian women merging with fruits, other objects, and architecture, or just living their best lives in a fantasy world. A viral video called Auntlantis, which has racked up 13.5 million views on Instagram, imagines silver-haired aunties as industrial mermaids working in an underwater trash-processing plant.

There’s also Granny Spills, an AI video account that features a glamorous, sassy old lady spitting hot takes and life advice to a street interviewer. It gained 1.8 million Instagram followers within three months of launch, posting new videos almost every day. Although the granny’s face looks slightly different in every video, the pink color scheme and her outfit stay mostly consistent. Creators Eric Suerez and Adam Vaserstein tell me that their entire workflow is powered by AI, from writing the script to constructing the scenes. Their role, as a result, becomes close to creative directing.

These projects often spin off merch, miniseries, and branded universes. The creators of Granny Spills, for example, have expanded their network, creating a Black granny as well as an Asian granny to cater to different audiences. The grannies now appear in crossover videos, as if they share the same fictional universe, pushing traffic between channels.

In the same vein, it’s now more possible than ever to participate in an online trend. Consider “Italian brainrot,” which went viral earlier this year. Beloved by Gen Z and Gen Alpha, these videos feature human–animal–object hybrids with pseudo-Italian names like “Bombardiro Crocodilo” and “Tralalero Tralala.” According to Know Your Meme, the craze began with a few viral TikTok sounds in fake Italian. Soon, a lot of people were participating in what felt like a massive collaborative hallucination, inventing characters, backstories, and worldviews for an ever-expanding absurdist universe.

“Italian brainrot was great when it first hit,” says Denim Mazuki, a software developer and content creator who has been following the trend. “It was the collective lore-building that made it wonderful. Everyone added a piece. The characters were not owned by a studio or a single creator—they were made by the chronically online users.”

This trend and others are further enabled by specialized and sophisticated new tools—like OpenArt, a platform designed not just for video generation but for video storytelling, which gives users frame-to-frame control over a developing narrative.

Making a video on OpenArt is straightforward: Users start with a few AI-generated character images and a line of text as simple as “cat dancing in a park.” The platform then spins out a scene breakdown that users can tweak act by act, and they can run it through multiple mainstream models and compare the results to see which look best.

OpenArt cofounders Coco Mao and Chloe Fang tell me they sponsored tutorial videos and created quick-start templates to capitalize specifically on the trend of regular people wanting to get in on Italian brainrot. They say more than 80% of their users have no artistic background.

In defense of slop

The current use of the word “slop” online traces back to the early 2010s on 4chan, a forum known for its insular and often toxic in-jokes. As the term has spread, its meaning has evolved; it’s now a kind of derogatory slur for anything that feels like low-quality mass production aimed at an unsuspecting public, says Adam Aleksic, an internet linguist. People now slap it onto everything from salad bowls to meaningless work reports.

But even with that broadened usage, AI remains the first association: “slop” has become a convenient shorthand for dismissing almost any AI-generated output, regardless of its actual quality. The Cambridge Dictionary’s new sense of “slop” will almost certainly cement this perception, describing it as “content on the internet that is of very low quality, especially when it is created by AI.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the word has become a charged label among AI creators.

Anselmo embraces it semi-ironically, hence the title of his yearslong art project. “I see this series as an experimental sketchbook,” he says. “I am working with the slop, pushing the models, breaking them, and developing a new visual language. I have no shame that I am deep into AI.” Anselmo says that he does not concern himself with whether his work is “art.”

Garibay, the creator of the viral video where a human face emerged from a pot of physical slop, uses the label playfully. “The AI slop art is really just a lot of weird glitchy stuff that happens, and there’s not really a lot of depth usually behind it, besides the shock value,” he says. “But you will find out really fast that there is a heck of a lot more involved, if you want a higher-end result.”

That’s largely in line with what Suerez and Vaserstein, the creators of Granny Spills, tell me. They actually hate it when their work is called slop, given the way the term is often used to dismiss AI-generated content out of hand. It feels disrespectful of their creative input, they say. Even though they do not write the scripts or paint the frames, they say they are making legitimate artistic choices.

Indeed, for most of the creators I spoke to, making AI content is rarely a one-click process. They tell me that it takes skill, trial and error, and a strong sense of taste to consistently get the visuals they want. Lim says a single one-minute video can take hours, sometimes even days, to make. Anselmo, for his part, takes pride in actively pushing the model rather than passively accepting its output. “There’s just so many things that you can do with it that go well beyond ‘Oh, way to go, you typed in a prompt,’” he says. Ultimately, slop evokes a lot of feelings. Aleksic puts it well: “There’s a feeling of guilt on the user end for enjoying something that you know to be lowbrow. There’s a feeling of anger toward the creator for making something that is not up to your content expectations, and all the meantime, there’s a pervasive algorithmic anxiety hanging over us. We know that the algorithm and the platforms are to blame for the distribution of this slop.”

And that anxiety long predates generative AI. We’ve been living for years with the low-grade dread of being nudged, of having our taste engineered and our attention herded, so it’s not surprising that the anger latches onto the newest, most visible culprit. Sometimes it is misplaced, sure, but I also get the urge to assert human agency against a new force that seems to push all of us away from what we know and toward something we didn’t exactly choose.

But the negative association has real harm for the earlier adopters. Every AI video creator I spoke to described receiving hateful messages and comments simply for using these tools at all. These messages accuse AI creators of taking opportunities away from artists already struggling to make a living, and some dismiss their work as “grifting” and “garbage.” The backlash, of course, did not come out of nowhere. A Brookings study of one major freelance marketplace found that after new generative-AI tools launched in 2022, freelancers in AI-exposed occupations saw about 2% decline in contracts and a 5% drop in earnings.

“The phrase ‘AI slop’ implies, like, a certain ease of creation that really bothers a lot of people—understandably, because [making AI-generated videos] doesn’t incorporate the artistic labor that we typically associate with contemporary art,” says Mindy Seu, a researcher, artist, and associate professor in digital arts at UCLA.

At the root of the conflict here is that the use of AI in art is still nascent; there are few best practices and almost no guardrails. And there’s a kind of shame involved—one I recognize when I find myself lingering on bad AI content.

Historically, new technology has always carried a whiff of stigma when it first appears, especially in creative fields where it seems to encroach on a previously manual craft. Seu says that digital art, internet art, and new media have been slow to gain recognition from cultural institutions, which remain key arbiters of what counts as “serious” or “relevant” art.

For many artists, AI now sits in that same lineage: “Every big advance in technology yields the question ‘What is the role of the artist?’” she says. This is true even if creators are not seeing it as a replacement for authorship but simply as another way to create.

Mao, the OpenArt founder, believes that learning how to use generative video tools will be crucial for future content creators, much as learning Photoshop was almost synonymous with graphic design for a generation. “It is a skill to be learned and mastered,” she says.

There is a generous reading of the phenomenon so many people call AI slop, which is that it is a kind of democratization. A rare skill shifts away from craftsmanship to something closer to creative direction: being able to describe what you want with enough linguistic precision, and to anchor it in references the model is likely to understand. You have to know how to ask, and what to point to. In that sense, discernment and critique sit closer to the center of the process than ever before.

It’s not just about creative direction, though, but about the human intention behind the creation. “It’s very easy to copy the style,” Lim says. “It’s very easy to make, like, old Asian women doing different things, but they [imitators] don’t understand why I’m doing it … Even when people try to imitate that, they don’t have that consistency.”

“It’s the idea behind AI creation that makes it interesting to look at,” says Zach Lieberman, a professor at the MIT Media Lab who leads a research group called Future Sketches, where members explore code-enabled images. Lieberman, who has been posting daily sketches generated by code for years, tells me that mathematical logic is not the enemy of beauty. He echoes Mao in saying that a younger generation will inevitably see AI as just another tool in the toolbox. Still, he feels uneasy: By relying so heavily on black-box AI models, artists lose some of the direct control over output that they’ve traditionally enjoyed.

A new online culture

For many people, AI slop is simply everything they already resent about the internet, turned up: ugly, noisy, and crowding out human work. It’s only possible because it’s been trained to take all creative work and make it fodder, stripped of origin, aura, or credit, and blended into something engineered to be mathematically average—arguably perfectly mediocre, by design. Charles Pulliam-Moore, a writer for The Verge, calls this the “formulaic derivativeness” that already defines so much internet culture: unimaginative, unoriginal, and uninteresting.

But I love internet culture, and I have for a long time. Even at its worst, it’s bad in an interesting way: It offers a corner for every kind of obsession and invites you to add your own. Years of being chronically online have taught me that the real logic of slop consumption isn’t mastery but a kind of submission. As a user, I have almost no leverage over platforms or algorithms; I can’t really change how they work. Submission, though, doesn’t mean giving up. It’s more like recognizing that the tide is stronger than you and choosing to let it carry you. Good scrolling isn’t about control anyway. It’s closer to surfing, and sometimes you wash up somewhere ridiculous, but not entirely alone.

Mass-produced click-bait content has always been around. What’s new is that we can now watch it being generated in real time, on a scale that would have been unimaginable before. And the way we respond to it in turn shapes new content (see the trampoline-bouncing bunnies) and more culture and so on. Perhaps AI slop is born of submission to algorithmic logic. It’s unserious, surreal, and spectacular in ways that mirror our relationship to the internet itself. It is so banal—so aggressively, inhumanly mediocre—that it loops back around and becomes compelling.

To “love AI slop” is to admit the internet is broken, that the infrastructure of culture is opportunistic and extractive. But even in that wreckage, people still find ways to play, laugh, and make meaning.

Earlier this fall, months after I was briefly fooled by the bunny video, I was scrolling on Rednote and landed on videos by Mu Tianran, a Chinese creator who acts out weird skits that mimic AI slop. In one widely circulated clip, he plays a street interviewer asking other actors, “Do you know you are AI generated?”—parodying an earlier wave of AI-generated street interviews. The actors’ responses seem so AI, but of course they’re not: Eyes are fixed just off-camera, their laughter a beat too slow, their movements slightly wrong.

Watching this, it was hard to believe that AI was about to snuff out human creativity. If anything, it has handed people a new style to inhabit and mock, another texture to play with. Maybe it’s all fine. Maybe the urge to imitate, remix, and joke is still stubbornly human, and AI cannot possibly take it away.