There is a shirt currently listed on eBay for $2,128.79. It was not designed by Versace or Dior, nor spun from the world’s finest silk. In fact, a tag proudly declares, “100% cotton made in Myanmar”—but it’s a second tag, just below that one, that makes this blue button-down so expensive.

“I looked at it and I was like, Wow, this is cool,” says Brooke Hermann, the 30-year-old Kentucky-based reseller who bought the top for $1 at a secondhand sale in 2024. “This doesn’t look like any other Fruit of the Loom tag I’ve ever seen.”

Quick question: Does the Fruit of the Loom logo feature a cornucopia?

Many of us have been wearing the casualwear company’s T-shirts and underpants for decades, and yet the question of whether there is a woven brown horn of plenty on the logo is surprisingly contentious. According to a 2022 poll by the research company YouGov, 55% of Americans believe the logo does include a cornucopia, 25% are unsure, and only 21% are confident that it doesn’t, even though this last group is correct. According to a 2023 post from the company, the Fruit of the Loom logo does not include—and, according to Snopes, has never included—a horn of plenty. (MIT Technology Review could not reach Fruit of the Loom for comment.)

This story is part of MIT Technology Review’s series “The New Conspiracy Age,” on how the present boom in conspiracy theories is reshaping science and technology.

Maybe you’ve come across this fact before, via an internet meme that made you gasp, shrug, or scratch your head. There’s a specific name for what’s happening here: Those who believe the logo used to include the cornucopia are experiencing the “Mandela effect,” or collective false memory, so called because a number of people misremember that Nelson Mandela died in prison. I helped popularize the phenomenon in a viral 2016 New Statesman article about a movie that doesn’t actually exist, and in the time since it’s become something of a household term; TV shows from Saturday Night Live to Black Mirror to The X-Files have explored the Mandela effect.

But whether you remember the brown horn, incorrectly recall Darth Vader saying, “Luke, I am your father,” or believe that a popular children’s book was spelled The Berenstein Bears, you’ve probably moved on with your life. Google searches for “Mandela effect” have plummeted from 2016 highs, and Hermann has had zero bids on the shirt she posted last year—even though, at least to her eyes, it features a cornucopia on the tag. “No one’s really offered anything, and no one’s said anything about it,” she says, “which to me is kind of crazy.”

And yet while many find it easy to let their unconfirmable beliefs go, others have spent the better part of a decade seeking answers—and vindication. There are commonly more than 170,000 weekly visitors to a Mandela effect subreddit that sees over 1,000 comments on average every day. While a fair share of these commenters are skeptics, plenty more are dedicated believers who are not satisfied with the prevailing explanation that human memory is fallible and instead invest their time into bringing the truth—whatever exactly it may be—to light.

“I’ve been a bit ostracized from my family ever since I started pushing this thing nine years ago,” says a 51-year-old Massachusetts-based Fruit of the Loom truther who asked to go by the name AJ Booras. “I’m not inclined to simply let this phenomenon fall by the proverbial wayside, even if I’m the last one standing.”

Some online believe in a fairly straightforward conspiracy: They want Fruit of the Loom to confess that it’s “gaslighting” customers and used to have a cornucopia on its tags. Others speculate that the answer lies in quantum physics: If—as the astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson has said—there’s “better than 50-50 odds” that we’re living in a simulation, then might there be some sort of glitch, lag, or failed software update that means some people see and remember the world differently from others?

“The scientific community isn’t really looking that hard at it—and if they are, they’re always framing it as a memory thing,” says AJ. “It’s a hard barrier to make any headway on.” This is why, AJ says, he’s become “addicted” to researching the phenomenon: “It’s a personal quest for vindication.”

Will anyone ever believe these believers? There are two options for those who think the Fruit of the Loom logo once had a cornucopia: accept that your memory is wrong, or think that the world is. What makes some people happy with the simple explanation and others determined to seek the more complicated one?

“The bridge between perception and memory”

There’s nothing quite as disconcerting as when memory and reality conflict. After all, what is reality—or at least your reality—if not your memory? This is why it can be so satisfying to find concrete evidence that you are irrefutably correct: Here’s an old photo that proves Dad did come on the ’09 trip to Florida and your sister is foolish and wrong.

In the Mandela effect community, evidence implying that the world used to be different is called “residue.” There is an abundant amount of residue suggesting that the Fruit of the Loom logo once had a cornucopia.

In the 2006 animated film The Ant Bully, a pair of parodical “Fruit of the Loin” underwear is drawn with a cornucopia on the tag. A similar gag in a 2012 episode of South Park sees a fake clothing brand named “Cornucopia.” In 1973, when the jazz flutist Frank Wess released an album called Flute of the Loom, the cover showed fruit pouring out a cornucopia-shaped flute. When allegedly tracked down by Redditors, the illustrator reportedly said the clothing logo had inspired the design: “Why the hell else would I have used a cornucopia?”

On top of that, numerous newspaper and magazine articles written from the 1970s to the early 2000s reference the horn of plenty, as does a short play first performed in 1968 and a novel, The Brothers K, published in 1992. New residue is still being discovered: In April 2025, a TikToker shared an old ’90s trivia game in which clues about brands are listed on cards. The card for Fruit of the Loom includes the words “underwear,” “apples and grapes,” and “cornucopia.”

How can all these people—animators, illustrators, journalists, and writers—have made the same mistake? When I reached out to the author of The Brothers K, David James Duncan, he was adamant that there was no mistake: “My inspiration was the Fruit of the Loom boxer shorts I owned at the time,” he said via email. “I changed nothing in describing the boxers, and yes, they did have a Fruit of the Loom cornucopia on the label in the back of the shorts.”

Conversely, when I spoke with Billy Cox, a journalist who referenced the cornucopia in a 1994 article in Florida Today, he was less confident. “I have no idea what fueled my initial assumption about the cornucopia. Zero. Zilch-o. Nada,” said Cox, also via email. But he’s prepared to admit that he may have been careless in his reporting: “Even if the internet had been available back then, I doubt I would’ve double-checked the logo’s history.”

It’s an interesting thought: Most of the articles referencing the cornucopia are from a period—the ’70s through the ’90s—when journalists wouldn’t have been able to quickly google the logo. But why would they all misremember it the exact same way?

Wilma Bainbridge is an associate psychology professor at the University of Chicago who researches what she calls “the bridge between perception and memory”; she got her PhD in brain and cognitive sciences from MIT in 2016.

Bainbridge herself first came across the Mandela effect on social media—she was “wowed” when confronted with the true spelling of the Berenstain Bears in the famous American children’s books. In 2022, she published a scientific study on visual Mandela effects and ultimately found that there is consistency in what people misremember. “People’s memories are surprisingly predictable,” she says.

The husband-and-wife team of Stanley and Janice Berenstain wrote and illustrated the popular children’s books. More than 300 titles bear the family name.

In one experiment in the study, she found that people who aren’t very familiar with an image can share the same false memories as those who claim to be highly familiar. For example, some Mandela effect experiencers believe that the Monopoly man wore a monocle. In Bainbridge’s study, even people who didn’t know the character well sometimes drew the monocle when they were shown the Monopoly man and were later asked to draw him; this means the mistake was based on recall, not recognition, and could suggest that there’s something intrinsic to certain images that encourages memory errors.

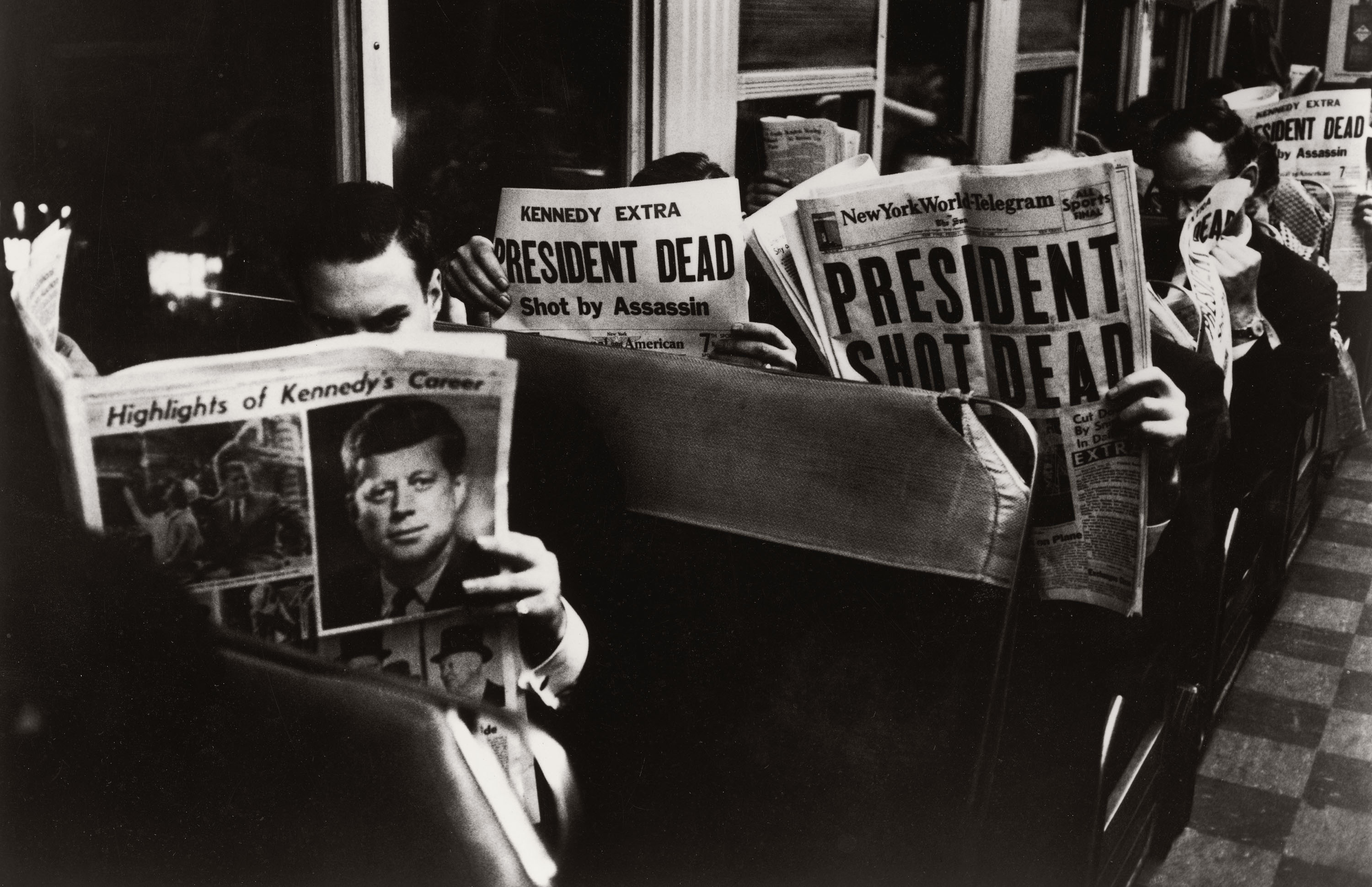

Scientists have long demonstrated that human memory is inherently fallible. In 1996, psychologists asked people whether they had watched news footage of the 1992 Bijlmer plane crash in Amsterdam, and more than 60% of the participants said yes—even though no recording of the crash exists. Other studies have shown that our memories can be corrupted by our peers and that false memories can be contagious. Arguably, the internet has caused memory contagion when it comes to the Mandela effect: Comparatively very few people googled “Fruit of the Loom cornucopia” between 2004 and 2017, with searches growing more common after a Redditor pointed out what was believed to be the first piece of “residue” in 2016 and (and again spiking dramatically when a TikTok video on the phenomenon was posted in 2023; it’s since earned over 5 million views).

“Some people make things go viral because they want to believe it,” says Don, a 61-year-old American who has been moderating the Mandela effect subreddit since 2017. (He asked to be identified only by his first name to protect his privacy.) “People want to be part of the experience.”

Still, Bainbridge’s study didn’t land on one definitive reason for the Mandela effect. “I was surprised to find there was no singular explanation,” she says.

Using a method of monitoring cursor movement that’s analogous to eye-tracking technology, the academic tested whether people made memory errors because they didn’t pay attention to an image or looked at only certain parts of it. She found this wasn’t the case.

Could it be, then, that people simply fill in the blanks of their memory with archetypes—we remember the Monopoly man with a monocle because we associate the eyepiece with rich old men?

Bainbridge has found that this explanation—known as the “schema theory”—cannot fully explain the Mandela effect either. In one of her experiments, participants were asked to select the correct Fruit of the Loom logo from three images: one without a cornucopia, one with a cornucopia, and one with a plate. Even though we see fruit on plates far more often than we see it inside cornucopias, more participants selected the horn of plenty than the crockery.

Bainbridge is drawn to the idea that some images simply cause more false memories than others. “We think the underlying cause will not likely be a single feature—e.g., attractiveness, color—but how these features work together in relation to things already stored in our memory,” she says. “But this work is still in its early stages, so we don’t know exactly what that combination is like.”

Believers like AJ just aren’t convinced.

“In simulation, anything can happen”

“A lot of people remember looking at this unfamiliar object on their underwear tag,” says AJ, “and asking a parent, ‘Is that a loom?’ and the parents saying, ‘No! That’s what we call a cornucopia.’”

When he was growing up in the ’70s and ’80s, AJ wore Fruit of the Loom underwear and regularly folded laundry with his mother. “You stack up enough underwear, and you’re seeing that logo over and over and over again,” he says.

As a newly fledged adult around the late ’90s, AJ had to go to the store and buy his own underwear for the first time. “I noticed,” he says, “that the logo had changed, and it was just a pile of fruit.”

Unperturbed, AJ assumed the company had just rebranded—he didn’t worry about it too much until almost two decades later, when he came across the Mandela effect online and realized the consensus was that there had never been a cornucopia. “We call it the wave of 2016 in the Mandela effect community—it was this huge rush of many, many effects that were being noticed,” he says.

The first time he heard about the Mandela effect, AJ says, he “actually swooned” because of an “overwhelming existential dread that something was dreadfully wrong with reality itself.”

Today, AJ believes in numerous instances of the Mandela effect, all of which have been shown to be incorrect but nonetheless have robust believer communities online: that the pizza roll brand used to be called Tostino’s, not Totino’s; that the location of Australia has moved on the world map; that the show Sex and the City was Sex in the City; Froot Loops cereal was formerly Fruit Loops; human organs have shifted positions; the sun changed color from yellow to white …

For him, each is just one part of a larger problem he can’t explain about the universe. At first, AJ says, he sought answers by researching memory science and psychology, but he was left unsatisfied. So instead, he looked to quantum mechanics and metaphysics, specifically ontology—the study of reality.

In 2003, the philosopher Nick Bostrom—famous for his theories on the threat of AI “superintelligence”—posited that humanity may be living inside a simulation. Almost two decades later, the astronomer David Kipping performed some calculations and put the odds at 50-50. “In simulation, anything can happen,” AJ says. “You could have different servers—one server hasn’t been updated, some people are seeing one version, some people are seeing the other.” It is also possible, AJ argues, that we exist in a multiverse—an idea first floated by the physicist Hugh Everett III in the 1950s. If people are somehow traveling between these parallel universes, then they may have memories from different worlds. Both of these theories are recurrent in the Mandela effect community online.

And yet AJ doesn’t find these explanations entirely fulfilling: “If we jumped universes, why would there be residue?” Instead, he’s been diving into a combination of the theoretical physicist John Archibald Wheeler’s concept of the Participatory Anthropic Principle (PAP)—which suggests, controversially, that the act of observation creates reality—and the Nobel Prize–winning physicist Eugene Wigner’s “friend” experiment, which theorized that two observers can experience two different realities. AJ believes that physicists’ own work may be affecting the universe: “It’s almost like you’re changing the parameters of reality itself by digging deeper.”

There is still so much that the experts themselves can’t explain about quantum physics, so it’s no wonder that laypeople get confused. The internet offers myriad rabbit holes to go down, some of them legitimate and some of them less so. Things are complicated further when YouTubers and internet commenters who aren’t well versed in the science take specific, highly complex theories and experiments and try to apply them to other phenomena, even if there is no concrete evidence they’re related. So I set about emailing physicists, simply to see whether they believe it might be remotely possible that quantum physics could, in fact, explain the Mandela effect.

Numerous academics replied telling me they had nothing to say on the topic; Bostrom’s office said he was unavailable. I asked the theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli—who has been labelled one of the world’s 50 top thinkers—whether he has any thoughts about Mandela effect believers’ quantum-physics-related theories. “Yes, definitely,” he replied. “They are all total bullshit! There are few things about which I am totally convinced. This is one.”

I contacted the University of Oxford physicist David Deutsch—often called the “father of quantum computing”—and listed the theories believers think may explain the Mandela effect, including parallel universes, simulations, the holographic principle, PAP, and Wigner’s friend idea. “Considered as explanations of the Mandela effect, none of those follow from quantum theory, and none of them constitute a rational speculation beyond it,” he said. Johns Hopkins University professor and physicist Sean M. Carroll concurs: “I cannot imagine how any of those phenomena could be in any way related to the Mandela effect.”

Melvin Vopson, an associate professor of physics at the University of Portsmouth who has conducted research on the simulation theory, admits he has experienced the Mandela effect himself but doesn’t attribute the phenomenon to glitches in the simulation: That’d be a “cheap explanation,” he says.

Nevertheless, scientists waving away these explanations could have a detrimental effect: In the absence of expert engagement, there are plenty of people online who can bolster believers’ views. AJ is not surprised by these responses: “I just don’t think that physicists have given it a real hard look,” he says, “because they’re already certain that it’s explainable otherwise.”

Bainbridge, for her part, thinks her study at least disproves the theory that we’ve been jumping between different universes. When she took those study participants who weren’t familiar with certain logos and mascots and showed them the correct version for the first time, she tested their memory by asking them to redraw the image only moments later, and still some drew the Mandela effect version.

“It’s unlikely we jumped dimensions during that short time span,” she says, “so it seems like the Mandela effect is something more about the shortcuts our memories take, rather than something about parallel worlds.” She hopes her future work will help further elucidate these “shortcuts,” and she is even planning to see whether she can create her own Mandela effects.

Leaving it all behind

One of the most well-documented memory phenomena is the “misinformation effect.” Since the 1970s, scientists have demonstrated that exposing people to misinformation after an event can alter their memories. If people are asked leading questions—say, “Did you see the broken headlight?” rather than “Did you see a broken headlight?” after witnessing a crash—they are more likely to report seeing something they didn’t. But on the flip side, warning witnesses about the threat of misinformation before they recount an event can increase the accuracy of their memory.

In short, the way information is presented to us is crucial. This is why it was pretty poor form for YouGov to poll Americans about the Fruit of the Loom logo with a question that was easily open to misinterpretation: “Does the logo for the clothing company Fruit of the Loom have a cornucopia of fruit in it, or not?” It is unclear here which part is in question—the cornucopia or the fruit. But it was also poor form that I didn’t mention this until now—nor did I mention that Neil deGrasse Tyson later changed his mind about simulation theory and is now “convinced” that we do not live in a simulation.

It was also probably pretty misleading of me to start this article with a link-free reference to Brooke Hermann’s eBay-listed shirt, which she believes features a cornucopia but to my eyes clearly features brown leaves. From the ’60s to the early ’00s, the Fruit of the Loom logo did include brown leaves behind the fruit; they were recolored green in 2003. When I started writing this article, I was certain that my Fruit of the Loom childhood PE kit had a cornucopia on the tag. I’m now convinced that 10-year-old me simply wasn’t looking that closely and thus I’ve misremembered the leaves as a horn. After all, even when I look at the current logo on shirts listed on the Fruit of the Loom website, my eyes still seem to want to make this mistake: From far away, I interpret the crowded cluster as a cornucopia.

The current Fruit of the Loom logo (left) and the version submitted in their 1973 trademark design application. Neither contain a cornucopia.

It’s as easy as that to convince me my memory was wrong—whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing, I’ll let you decide. I’m clearly at one end of some sort of spectrum here. Other Mandela effect experiencers may believe something stranger is going on but are still prepared to happily get on with their lives. Larry Jung is a thirtysomething musician who was living in New Jersey when he spent hours hunting for Fruit of the Loom residue; in 2019, he even purchased a copy of a 1969 book for around $20 so he could see the cornucopia reference within it. “I did obsess about it for a while in the beginning,” says Jung, who remembers the cornucopia because he mistook it for a croissant as a child. “But then—I don’t know, I just came to this acceptance phase. I just didn’t want it to affect my life in a big way. I didn’t want to bring it up in every discussion.”

Or, as another erstwhile Mandela effect researcher puts it: “If I just so happened to be living in a computer simulation, and that was my entire reality, what can I do about that?”

Don, the Mandela effect subreddit moderator, has seen waves of people move on while he has stayed active in the community for the better part of a decade (I first spoke to him for my New Statesman article in 2016). “I’ve recruited a lot of moderators, and they come and go pretty quick,” he says.

Don says he experiences “more than average but less than all” examples of the Mandela effect (he too remembers the cornucopia on his childhood underpants). “They find solutions that they find acceptable,” he says of some people who leave the sub. For others, the cognitive dissonance becomes “too much,” he adds. “It interferes with their ability to function.” Don theorizes that the people who stay are people who experienced the Mandela effect organically, “in the wild,” he says, “before it was a well-known phenomenon”—arguably the antithesis of people jumping on an internet bandwagon.

“I compare it to someone who saw Bigfoot. If you were in the woods and Bigfoot walks into your campground and he scares you and your kids, eight feet tall, smells terrible—you’re not going to forget it.”

AJ concurs that “anchor memories” like these are key. And yet Jung has a croissant-based anchor memory, and I myself have similar anecdotes about false memories I’ve found easy to let go. Psychologically, why does the Mandela effect affect people in such vastly different ways? Why do some people hold onto their memories while others don’t?

“We know that most people’s intuitions about memory are wrong; they think of it as an accurate recording device when in fact memory is a reconstructive apparatus that is presenting us with recollections based on very fragmented snippets,” says Stephan Lewandowsky, a cognitive psychologist at the University of Bristol who writes computer simulations of memory to better understand how the mind works. “So most people will have an exaggerated sense of the accuracy of their own memories and will refuse to accept that they could be completely false.”

In recent years, Lewandowsky has studied misinformation and has coauthored The Conspiracy Theory Handbook, and he says that while some people move on from their conspiracy theories, others turn them into their identity. “They will enter a state,” he says, “in which they are extremely difficult to extract from their rabbit hole.” People who become highly committed to conspiracies “tend to be disgruntled and feel left behind by society and are extremely distrustful,” Lewandowsky adds. “Those people also tend to be high in narcissism and often exhibit paranoid thoughts.”

Shauna Bowes is an assistant psychology professor at the University of Alabama who researches conspiratorial ideation, misinformation, and intellectual humility. Her work has found that people with this last quality—the tendency to acknowledge the limits of your own views—are less likely to believe misinformation.

“Belief perseverance is when you double down on your beliefs, even if evidence contradicts them,” Bowes says. “There are many reasons why some are willing to change their minds while others do not. Personality traits, childhood experiences, social networks, cognitive styles, and more determine these processes. What we do know is that people who tend to be more cognitively flexible, humble, and generally open-minded also tend to change their minds more in response to evidence.”

And yet when it comes to the Mandela effect, the question of “evidence” is a complicated one—after all, there’s plenty of cornucopia residue. Part of the trouble with understanding people’s responses to the Mandela effect is that the phenomenon can’t neatly be categorized as misinformation or conspiracy theory.

Lewandowsky believes the Mandela effect is primarily a social phenomenon. “My take on it is that if many people believe that an event has happened, that becomes a social norm that other people can support by sharing that belief. Social norms are very powerful,” he says, adding that the internet “provides a great amplification machine.”

Creating reality

AJ tells me that even though skeptics have called him “so many derogatory names over the last nine years,” he remains passionate about spreading word of the Mandela effect. He wants to “push a dialogue” so that believers don’t feel afraid to speak out. Mostly, AJ wants scientists to look at the qualitative side of things: the hundreds of autobiographical accounts by people with very specific memories of things that are now officially said not to have happened the way they recall. He wishes scientists would speak to experiencers directly, the same way the once-skeptical astronomer Josef Allen Hynek spoke to UFO eyewitnesses in the mid-20th century.

“Once upon a time, the UFO phenomenon was considered to be fringe. And now we have multiple world governments that have acknowledged that there is stuff flying around that we don’t know what it is,” AJ says. Overall, “the goal is to get the scientific establishment to at least consider the other side.”

Of course, AJ is not alone, even if Mandela effect believers do exist on a spectrum. The community holds space for people having fun with the phenomenon, for those committed to just a single example of the effect, for others who dive in on a short-term basis before moving on—and for those who have run the International Mandela Effect Conference in locations across the US since 2019.

And there’s Don, who is still moderating the subreddit after all these years and has seen believers of every stripe. “The thing that keeps me going is I want to make sure that it’s still here,” he says. “There’s a lot of history here, and I want to keep it around for that reason.”

Personally, he believes there may be different explanations for different examples of the Mandela effect. It could be as simple as people confusing Fruit of the Loom with a knockoff brand, he says, or as complicated as Fruit of the Loom lying about the cornucopia as free advertising (though he also notes that no one has ever actually discovered an old Fruit of the Loom label with a cornucopia on it).

Don also wonders whether some people might be guinea pigs caught up in longitudinal studies in which psychologists play with subjects’ memories. He’s considered, too, that nefarious tech bros could be digitally manipulating and deleting data on the internet as a form of social engineering, a possibility he compares to the Cambridge Analytica affair. “It’s something that’s possible. I’m not saying that’s what’s happening,” he says. “But this is the kind of thing that could be being done.” (To be clear: Don shared no evidence that this is being done.)

Perhaps Don’s most interesting belief is that the Mandela effect is not a phenomenon but an “event”—one that may now in fact be over. In his opinion, there have been no significant or “persuasive” examples discovered since 2019 (when Redditors found that the character Baloo in Disney’s 1967 The Jungle Book never wore a coconut bra). Don believes the community peaked between 2015 and 2018, when people were making new discoveries regularly. “There was a period of time where it was an actual event, like this was an ongoing event,” he says. He compares the whole thing to medieval manias in which people danced themselves to death: “I think the fervor with which the Mandela effect spread will likely be compared to dancing plagues by future generations.”

Toward the end of my second of three calls with AJ, he asked me if I’d also experienced the Mandela effect. I explained that historically I experienced it with Fruit of the Loom, but I’m prepared to believe it was just a false memory. “Yeah, that’s fair,” he said. But I started to wonder if it is. When I wrote about the Mandela effect in 2016, I wanted to write an exciting story with twists and turns, which arguably played up the mystery. Am I responsible for making some people question reality? What are the consequences of writing another article, the one you’re currently reading? How much am I creating reality by observing it?

To be “fair” to AJ, should I tell you that one of memory science’s most famous studies has recently come under fire, and some academics now believe that people aren’t as susceptible to false memories as we once thought?

Or to be “fair” to you, the reader, should I stress that despite my own desire to believe in the mysteries of the universe, I’ve come away thinking that the biggest mystery of all is the human mind?

Amelia Tait is a London-based freelance features journalist who writes about culture, trends, and unusual phenomena.