On the ground in Ukraine’s largest Starlink repair shop

Oleh Kovalskyy thinks that Starlink terminals are built as if someone assembled them with their feet. Or perhaps with their hands behind their back.

To demonstrate this last image, Kovalskyy—a large, 47-year-old Ukrainian, clad in sweatpants and with tattoos stretching from his wrists up to his neck—leans over to wiggle his fingers in the air behind him, laughing as he does. Components often detach, he says through bleached-white teeth, and they’re sensitive to dust and moisture. “It’s terrible quality. Very terrible.”

But even if he’s not particularly impressed by the production quality, he won’t dispute how important the satellite internet service has been to his country’s defense.

Starlink is absolutely critical to Ukraine’s ability to continue in the fight against Russia: It’s how troops in battle zones stay connected with faraway HQs; it’s how many of the drones essential to Ukraine’s survival hit their targets; it’s even how soldiers stay in touch with spouses and children back home.

At the time of my visit to Kovalskyy in March 2025, however, it had begun to seem like this vital support system may suddenly disappear. Reuters had just broken news that suggested Musk, who was then still deeply enmeshed in Trump world, would remove Ukraine’s access to the service should its government fail to toe the line in US-led peace negotiations. Musk denied the allegations shortly afterward, but given Trump’s fickle foreign policy and inconsistent support of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky, the uncertainty of the technology’s future had become—and remains—impossible to ignore.

Kovalskyy’s unofficial Starlink repair shop may be the biggest of its kind in the world. Ordered chaos is the best way to describe it.

The stakes couldn’t be higher: Another Reuters report in late July revealed that Musk had ordered the restriction of Starlink in parts of Ukraine during a critical counteroffensive back in 2022. “Ukrainian troops suddenly faced a communications blackout,” the story explains. “Soldiers panicked, drones surveilling Russian forces went dark, and long-range artillery units, reliant on Starlink to aim their fire, struggled to hit targets.”

None of this is lost on Kovalskyy—and for now Starlink access largely comes down to the unofficial community of users and engineers of which Kovalskyy is just one part: Narodnyi Starlink.

The group, whose name translates to “The People’s Starlink,” was created back in March 2022 by a tech-savvy veteran of the previous battles against Russia-backed militias in Ukraine’s east. It started as a Facebook group for the country’s infant yet burgeoning community of Starlink users—a forum to share guidance and swap tips—but it very quickly emerged as a major support system for the new war effort. Today, it has grown to almost 20,000 members, including the unofficial expert “Dr. Starlink”—famous for his creative ways of customizing the systems—and other volunteer engineers like Kovalskyy and his men. It’s a prime example of the many informal, yet highly effective, volunteer networks that have kept Ukraine in the fight, both on and off the front line.

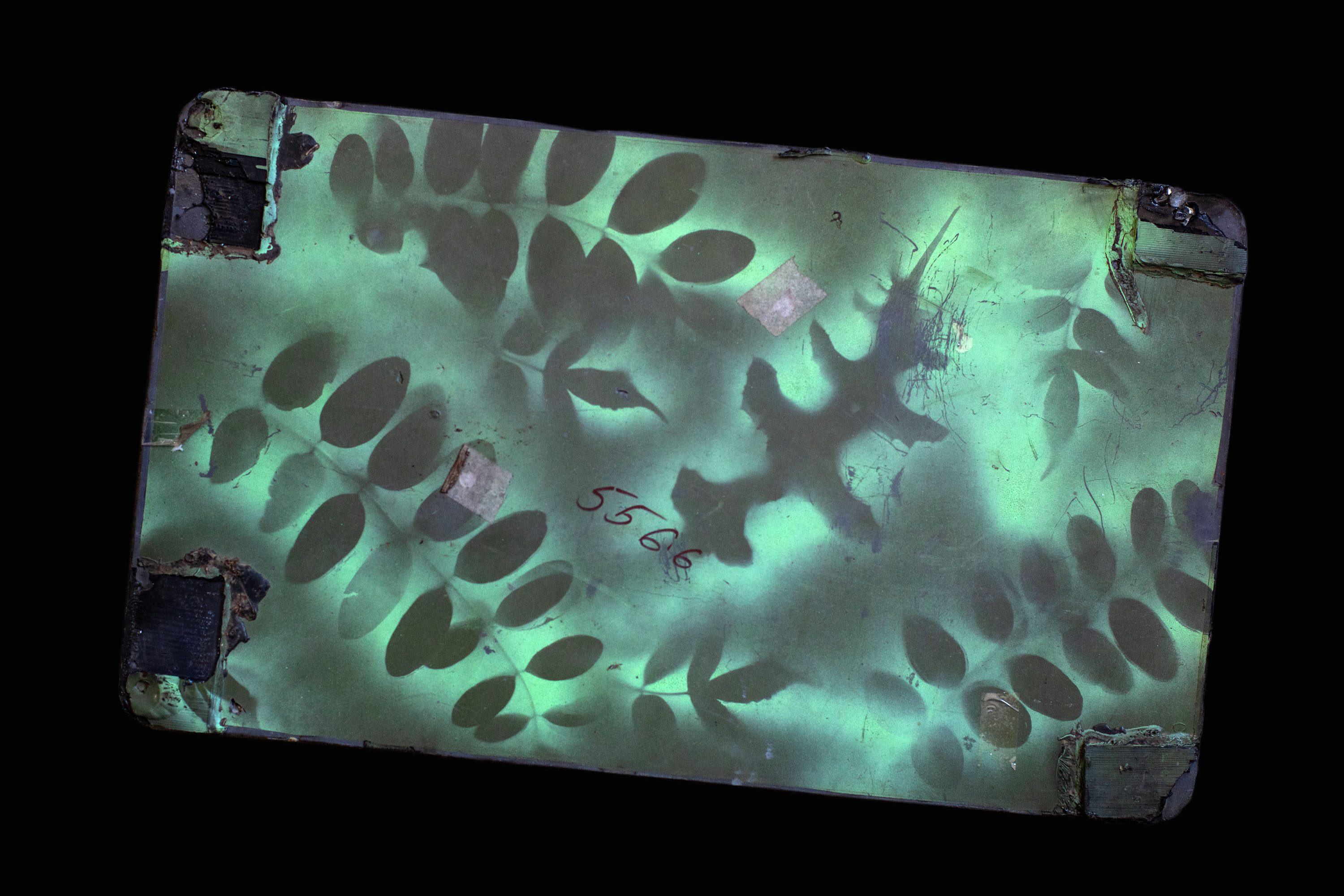

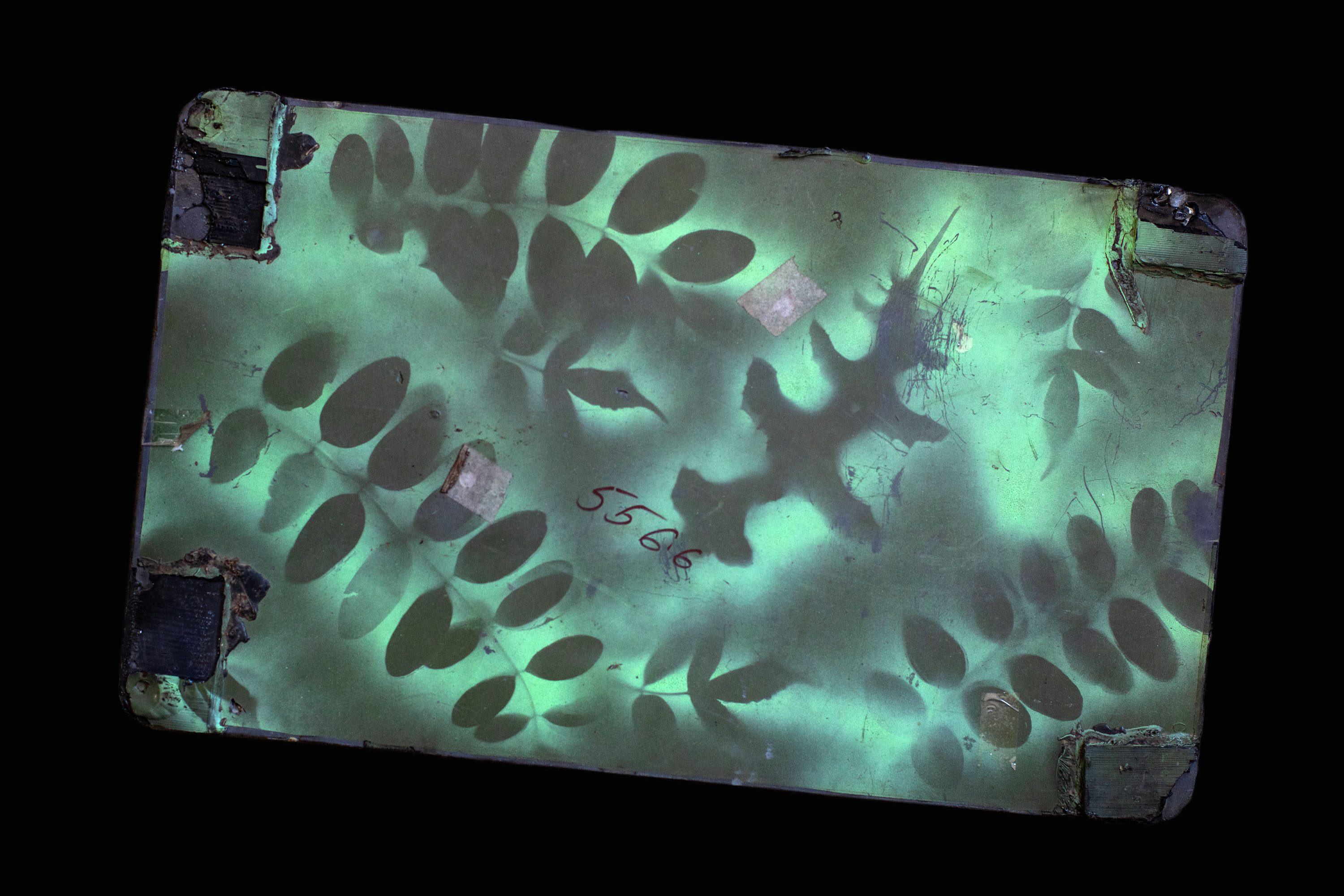

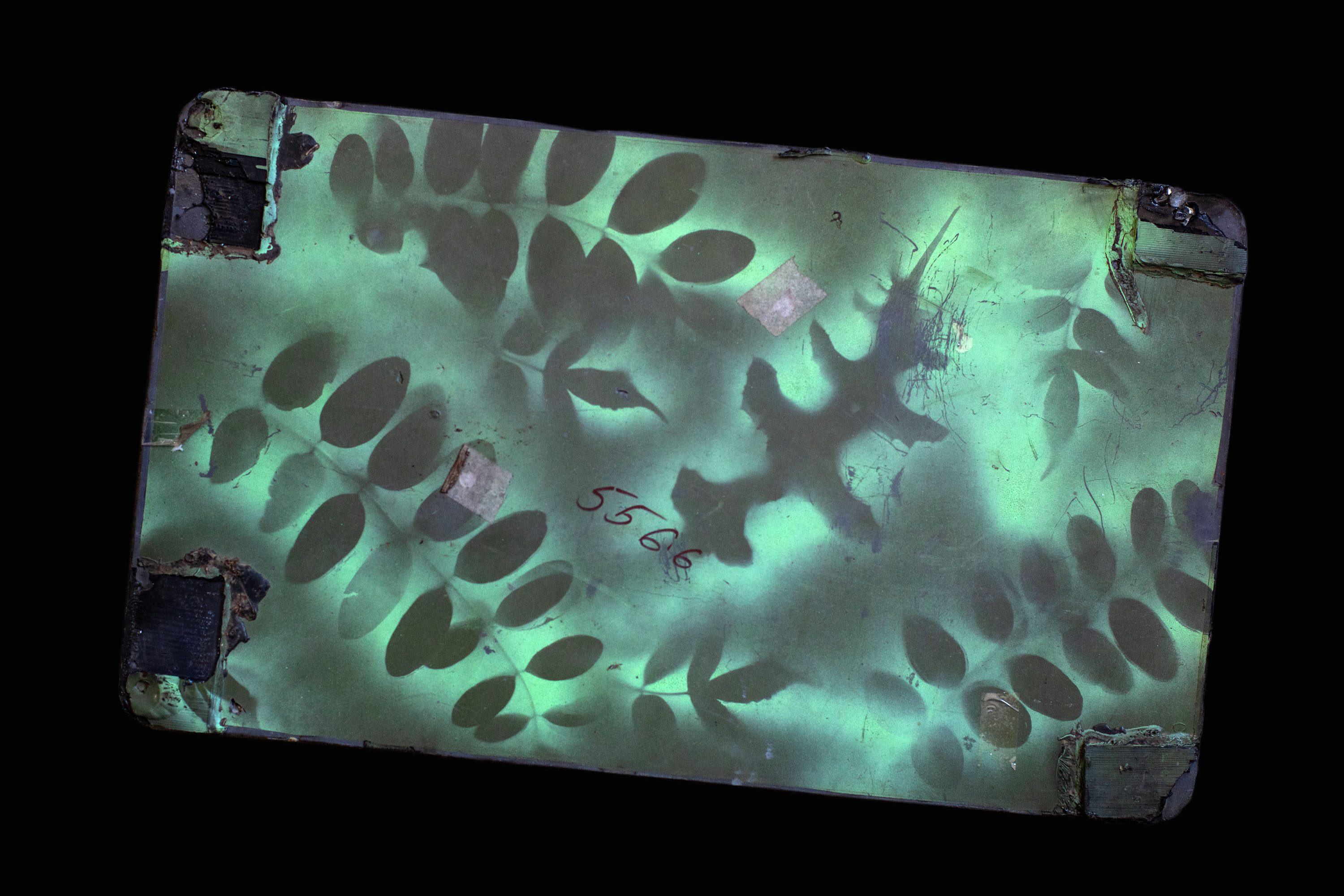

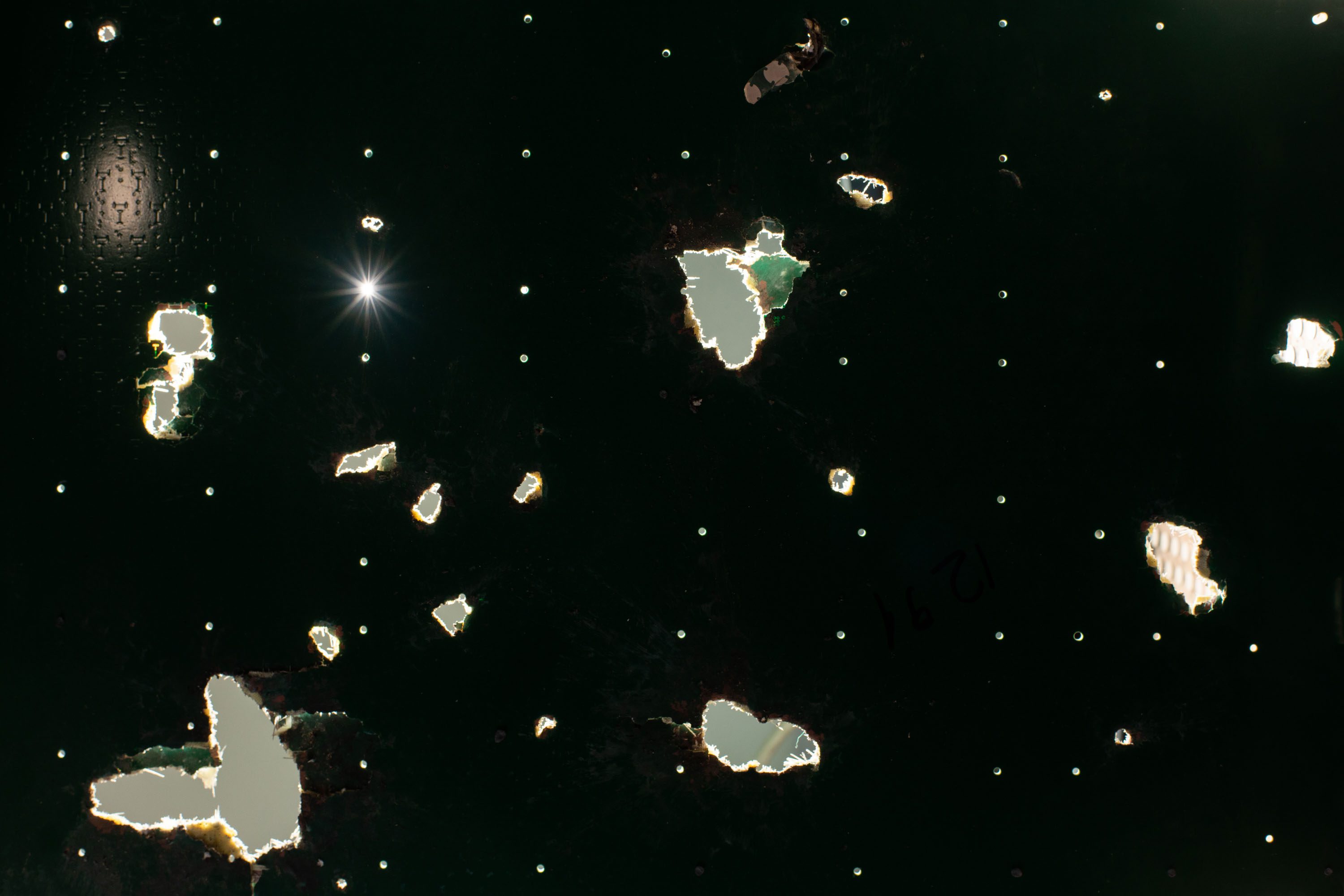

Kovalskyy and his crew of eight volunteers have repaired or customized more than 15,000 terminals since the war began in February 2022. Here, they test repaired units in a nearby parking lot.

Kovalskyy gave MIT Technology Review exclusive access to his unofficial Starlink repair workshop in the city of Lviv, about 300 miles west of Kyiv. Ordered chaos is the best way to describe it: Spread across a few small rooms in a nondescript two-story building behind a tile shop, sagging cardboard boxes filled with mud-splattered Starlink casings form alleyways among the rubble of spare parts. Like flying buttresses, green circuit boards seem to prop up the walls, and coils of cable sprout from every crevice.

Those acquainted with the workshop refer to it as the biggest of its kind in Ukraine—and, by extension, maybe the world. Official and unofficial estimates suggest that anywhere from 42,000 to 160,000 Starlink terminals operate in the country. Kovalskyy says he and his crew of eight volunteers have repaired or customized more than 15,000 terminals since the war began.

Despite the pressure, the chance that they may lose access to Starlink was not worrying volunteers like Kovalskyy at the time of my visit; in our conversations, it was clear they had more pressing concerns than the whims of a foreign tech mogul. Russia continues to launch frequent aerial bombardments of Ukrainian cities, sometimes sending more than 500 drones in a single night. The threat of involuntary mobilization to the front line looms on every street corner. How can one plan for a hypothetical future crisis when crisis defines every minute of one’s day?

Almost every inch of every axis of the battlefield in Ukraine is enabled by Starlink. It connects pilots near the trenches with reconnaissance drones soaring kilometers above them. It relays the video feeds from those drones to command centers in rear positions. And it even connects soldiers, via encrypted messaging services, with their family and friends living far from the front.

Although some soldiers and volunteers, including members of Narodnyi Starlink, refer to Starlink as a luxury, the reality is that it’s an essential utility; without it, Ukrainian forces would need to rely on other, often less effective means of communication. These include wired-line networks, mobile internet, and older geostationary satellite technology—all of which provide connectivity that is either slower, more vulnerable to interference, or more difficult for untrained soldiers to set up.

“If not for Starlink, we would already be counting rubles in Kyiv,” Kovalskyy says.

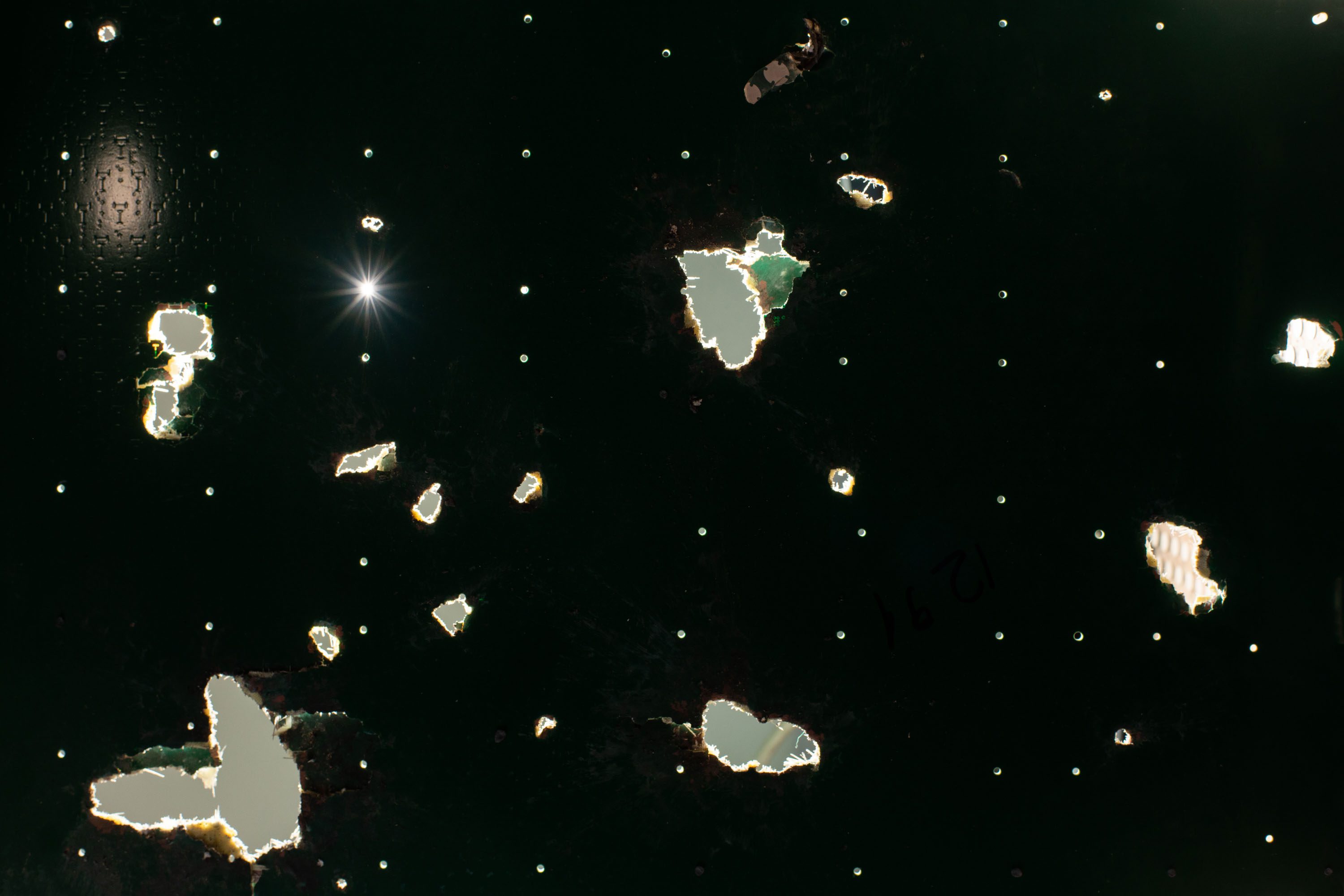

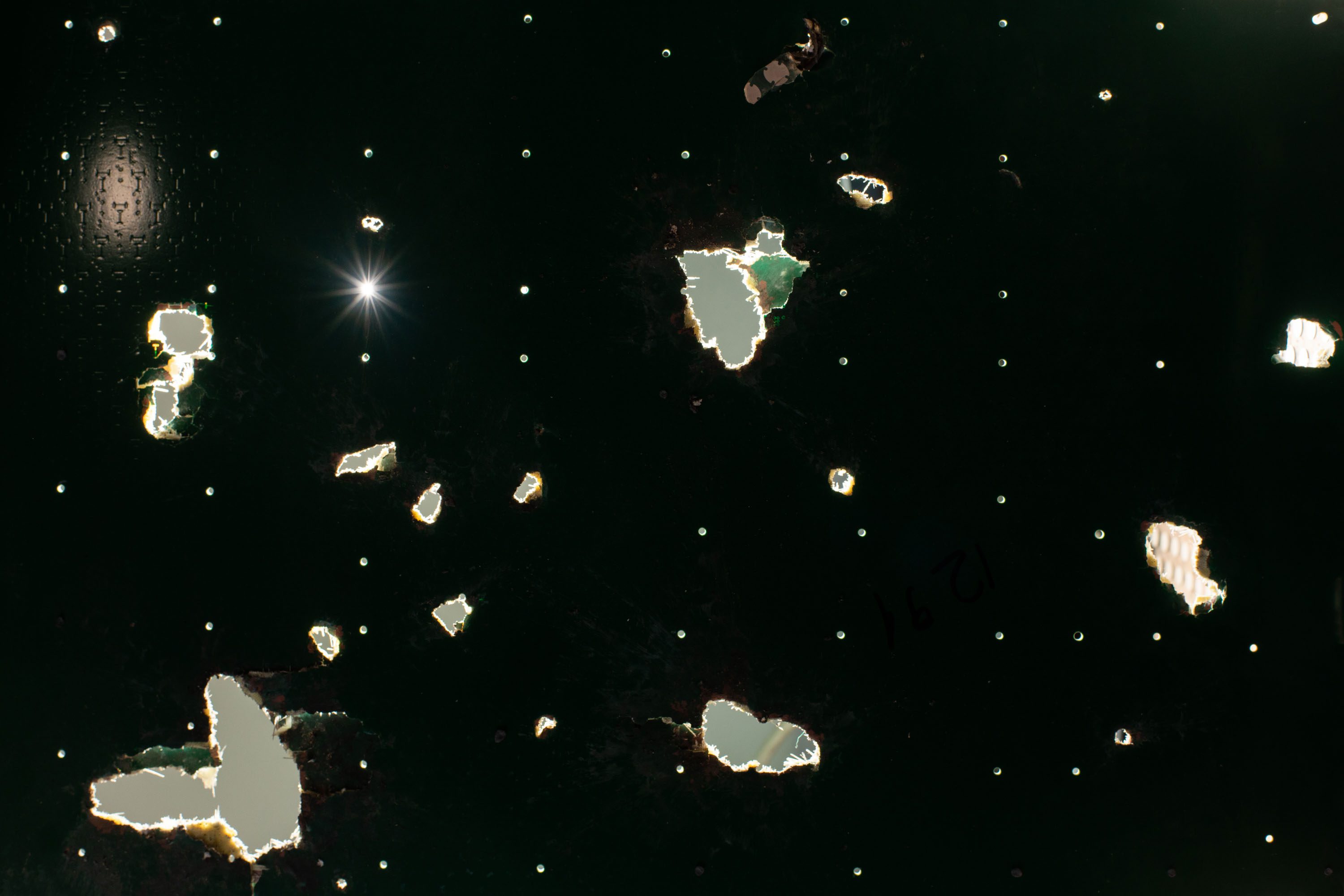

The workshop’s crew has learned to perform adjustments to terminals, especially in adapting them for battlefield conditions. At right, a volunteer engineer shows the fragments of shrapnel he has extracted from the terminals.

Despite being designed primarily for commercial use, Starlink provides a fantastic battlefield solution. The low-latency, high-bandwidth connection its terminals establish with its constellation of low-Earth-orbit satellites can transmit large streams of data while remaining very difficult for the enemy to jam—in part because the satellites, unlike geostationary ones, are in constant motion.

It’s also fairly easy to use, so that soldiers with little or no technical knowledge can connect in minutes. And the system costs much less than other military technology; while the US and Polish governments pay business rates for many of Ukraine’s Starlink systems, individual soldiers or military units can purchase the hardware at the private rate of about $500, and subscribe for just $50 per month.

No alternatives match Starlink for cost, ease of use, or coverage—and none will in the near future. Its constellation of 8,000 satellites dwarfs that of its main competitor, a service called OneWeb sold by the French satellite operator Eutelsat, which has only 630 satellites. OneWeb’s hardware costs about 20 times more, and a subscription can run significantly higher, since OneWeb targets business customers. Amazon’s Project Kuiper, the most likely future competitor, started putting satellites in space only this year.

Volodymyr Stepanets, a 51-year-old Ukrainian self-described “geek,” had been living in Krakow, Poland, with his family when Russia invaded in 2022. But before that, he had volunteered for several years on the front lines of the war against Russian-supported paramilitaries that began in 2014.

He recalls, in those early months in eastern Ukraine, witnessing troops coordinating an air strike with rulers and a calculator; the whole process took them between 30 and 40 minutes. “All these calculations can be done in one minute,” he says he told them. “All we need is a very stupid computer and very easy software.” (The Ukrainian military declined to comment on this issue.)

Stepanets subsequently committed to helping this brigade, the 72nd, integrate modern technology into its operations. He says that within one year, he had taught them how to use modern communication platforms, positioning devices, and older satellite communication systems that predate Starlink.

So after Russian tanks rolled across the border, Stepanets was quick to see how Starlink’s service could provide an advantage to Ukraine’s armed forces. He also recognized that these units, as well as civilian users, would need support in utilizing the new technology. And that’s how he came up with the idea for Narodnyi Starlink, an open Facebook group he launched on March 21, just a few weeks after the full invasion began and the Ukrainian government requested the activation of Starlink.

Over the past few years, the Narodnyi Starlink digital community has grown to include volunteer engineers, resellers, and military service members interested in the satellite comms service. The group’s members post roughly three times per day, often sharing or asking for advice about adaptations, or seeking volunteers to fix broken equipment. A user called Igor Semenyak recently asked, for example, whether anyone knew how to mask his system from infrared cameras. “How do you protect yourself from heat radiation?” he wrote, to which someone suggested throwing special heat-proof fabric over the terminal.

Its most famous member is probably a man widely considered the brains of the group: Oleg Kutkov, a 36-year-old software engineer otherwise known to some members as “Dr. Starlink.” Kutkov had been privately studying Starlink technology from his home in Kyiv since 2021, having purchased a system to tinker with when service was still unavailable in the country; he believes that he may have been the country’s first Starlink user. Like Stepanets, he saw the immense potential for Starlink after Russia broke traditional communication lines ahead of its attack.

“Our infrastructure was very vulnerable because we did not have a lot of air defense,” says Kutkov, who still works full time as an engineer at the US networking company Ubiquiti’s R&D center in Kyiv. “Starlink quickly became a crucial part of our survival.”

Stepanets contacted Kutkov after coming across his popular Twitter feed and blog, which had been attracting a lot of attention as early Starlink users sought help. Kutkov still publishes the results of his own research there—experiments he performs in his spare time, sometimes staying up until 3 a.m. to complete them. In May, for example, he published a blog post explaining how users can physically move a user account from one terminal to another when the printed circuit board in one is “so severely damaged that repair is impossible or impractical.”

“Oleg Kutkov is the coolest engineer I’ve met in my entire life,” Kovalskyy says.

When the fighting is at its worst, the workshop may receive 500 terminals to repair every month. The crew lives and sometimes even sleeps there.

Supported by Kutkov’s technical expertise and Stepanets’s organizational prowess, Kovalskyy’s warehouse became the major repair hub (though other volunteers also make repairs elsewhere). Over time, Kovalskyy—who co-owned a regional internet service provider before the war—and his crew have learned to perform adjustments to Starlink terminals, especially to adapt them for battlefield conditions. For example, they modified them to receive charge at the right voltage directly from vehicles, years before Starlink released a proprietary car adapter. They’ve also switched out Starlink’s proprietary SPX plugs—which Kovalskyy criticized as vulnerable to moisture and temperature changes—with standard ethernet ports.

Together, the three civilians—Kutkov, Stepanets, and Kovalskyy—effectively lead Narodnyi Starlink. Along with several other members who wished to remain anonymous, they hold meetings every Monday over Zoom to discuss their activities, including recent Starlink-related developments on the battlefield, as well as information security.

While the public group served as a suitable means of disseminating information in the early stages of the war when speed was critical, they have had to move a lot of their communications to private channels after discovering Russian surveillance; Stepanets says that at least as early as 2024, Russians had translated a 300-page educational document they had produced and shared online. Now, as administrators of the Facebook group, the three men block the publication of any posts deemed to reveal information that might be useful to Russian forces.

Stepanets believes the threat extends beyond the group’s intel to its members’ physical safety. When we talked, he brought up the attempted assassination of the Ukrainian activist and volunteer Serhii Sternenko in May this year. Although Sternenko was unaffiliated with Narodnyi Starlink, the event served as a clear reminder of the risks even civilian volunteers undertake in wartime Ukraine. “The Russian FSB and other [security] services still understand the importance of participation in initiatives like [Narodnyi Starlink],” Stepanets says. He stresses that the group is not an organization with a centralized chain of command, but a community that would continue operating if any of its members were no longer able to perform their roles.

The informal, accessible nature of this community has been critical to its success. Operating outside official structures has allowed Narodnyi Starlink to function much more efficiently than state channels. Yuri Krylach, a military communications officer who was inspired by Kovalskyy to set up his own repair workshop as part of Ukraine’s armed forces, says that official processes can be slower than private ones by a factor of 10; his own team’s work is often interrupted by other tasks that commanders deem more urgent, whereas members of the Narodnyi Starlink community can respond to requests quickly and directly. (The military declined to comment on this issue, or on any military connections with Narodnyi Starlink.)

Most of the Narodnyi Starlink members I spoke to, including active-duty soldiers, were unconcerned about the report that Musk might withdraw access to the service in Ukraine. They pointed out that doing so would involve terminating state contracts, including those with the US Department of Defense and Poland’s Ministry of Digitalization. Losing contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars (the Polish government claims to pay $50 million per year in subscription fees), on top of the private subscriptions, would cost the company a significant amount of revenue. “I don’t really think that Musk would cut this money supply,” Kutkov says. “It would be quite stupid.” Oleksandr Dolynyak, an officer in the 103rd Separate Territorial Defense Brigade and a Narodnyi Starlink member since 2022, says: “As long as it is profitable for him, Starlink will work for us.”

Stepanets does believe, however, that Musk’s threats exposed an overreliance on the technology that few had properly considered. “Starlink has really become one of the powerful tools of defense of Ukraine,” he wrote in a March Facebook post entitled “Irreversible Starlink hegemony,” accompanied by an image of the evil Darth Sidious from Star Wars. “Now, the issue of the country’s dependence on the decisions of certain eccentric individuals … has reached [a] melting point.”

Even if telecommunications experts both inside and outside the military agree that Starlink has no direct substitute, Stepanets believes that Ukraine needs to diversify its portfolio of satellite communication tools anyway, integrating additional high-speed satellite communication services like OneWeb. This would relieve some of the pressure caused by Musk’s erratic, unpredictable personality and, he believes, give Ukraine some sense of control over its wartime communications. (SpaceX did not respond to a request for comment.)

The Ukrainian military seems to agree with this notion. In late March, at a closed-door event in Kyiv, the country’s then-deputy minister of defense Kateryna Chernohorenko announced the formation of a special Space Policy Directorate “to consolidate internal and external capabilities to advance Ukraine’s military space sector.” The announcement referred to the creation of a domestic “satellite constellation,” which suggests that reliance on foreign services like Starlink had been a catalyst. “Ukraine needs to transition from the role of consumer to that of a full-fledged player in the space sector,” a government blog post stated. (Chernohorenko did not respond to a request for comment.)

Ukraine isn’t alone in this quandary. Recent discussions about a potential Starlink deal with the Italian government, for example, have stalled as a result of Musk’s behavior. And as Juliana Süss, an associate fellow at the UK’s Royal United Services Institute, points out, Taiwan chose SpaceX’s competitor Eutelsat when it sought a satellite communications partner in 2023.

“I think we always knew that SpaceX is not always the most reliable partner,” says Süss, who also hosts RUSI’s War in Space podcast, citing Musk’s controversial comments about the country’s status. “The Taiwan problems are a good example for how the rest of the world might be feeling about this.”

Nevertheless, Ukraine is about to become even more deeply enmeshed with Starlink; the country’s leading mobile operator Kyivstar announced in July that Ukraine will soon become the first European nation to offer Starlink direct-to-mobile services. Süss is cautious about placing too much emphasis on this development though. “This step does increase dependency,” she says. “But that dependency is already there.” Adding an additional channel of communications as a possible backup is otherwise a logical action for a country at war, she says.

These issues can feel far away for the many Ukrainians who are just trying to make it through to the next day. Despite its location in the far west of Ukraine, Lviv, home to Kovalskyy’s shop, is still frequently hit by Russian kamikaze drones, and local military-affiliated sites are popular targets.

Still, during our time together, Kovalskyy was far more worried by the prospect of his team’s possible mobilization. In March, the Ministry of Defense had removed the special status that had otherwise protected his people from involuntary conscription given the nature of their volunteer activities. They’re now at risk of being essentially picked up off the street by Ukraine’s dreaded military recruitment teams, known as the TCK, whenever they leave the house.

This is true even though there’s so much demand for the workshop’s services that during my visit, Kovalskyy expressed frustration at the vast amount of time they’ve had to dedicate solely to basic repairs. “We have extremely professional engineers who are extremely intelligent,” he told me. “Repairing Starlink terminals for them is like shooting ducks with HIMARS [a vehicle-borne GPS-guided rocket launcher].”

At least the situation seemed to have become better on the front over the winter, Kovalskyy added, handing me a Starlink antenna whose flat, white surface had been ripped open by shrapnel. When the fighting is at its worst, the team might receive 500 terminals to repair every month, and the crew lives in the workshop, sometimes even sleeping there. But at that moment in time, it was receiving only a couple of hundred.

We ended our morning at the workshop by browsing its vast collection of varied military patches, pinned to the wall on large pieces of Velcro. Each had been given as a gift by a different unit as thanks for the services of Kovalskyy and his team, an indication of the diversity and size of Ukraine’s military: almost 1 million soldiers protecting a 600-mile front line. At the same time, it’s a physical reminder that they almost all rely on a single technology with just a few production factories located on another continent nearly 6,000 miles away.

“We sometimes perform miracles with Starlinks,” Kovalskyy says.

He and his crew can only hope that they will still be able to for the foreseeable future—or, better yet, that they won’t need to at all.

Charlie Metcalfe is a British journalist. He writes for magazines and newspapers including Wired, the Guardian, and MIT Technology Review.