Why recycling alone can’t power climate tech

This article is from The Spark, MIT Technology Review’s weekly climate newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Wednesday, sign up here.

The potential to use old, discarded products to make something new sounds a little bit like magic. I absolutely understand the draw, and in some cases, recycling is going to be a crucial tool for climate technology. I’ve written about recycling for basically any climate technology you can think of, including solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries. (I’ve also covered efforts to recycle plastic waste.)

For my most recent story, I was researching the materials used for the magnets that power EVs and wind turbines. (Read the result here!) And once again, I was struck by a stark reality: there are massive challenges ahead in material demand for climate technologies, and unfortunately, recycling alone won’t be enough to address them. Let’s take a look at why recycling isn’t always the answer, and what else might help.

Mind the gap

We’re building a whole lot more climate technologies than we used to, which means there aren’t enough old, discarded technologies sitting around, waiting to be mined for materials. Obviously the growth in clean-energy technologies is a great thing for climate action. But it presents a problem for recycling.

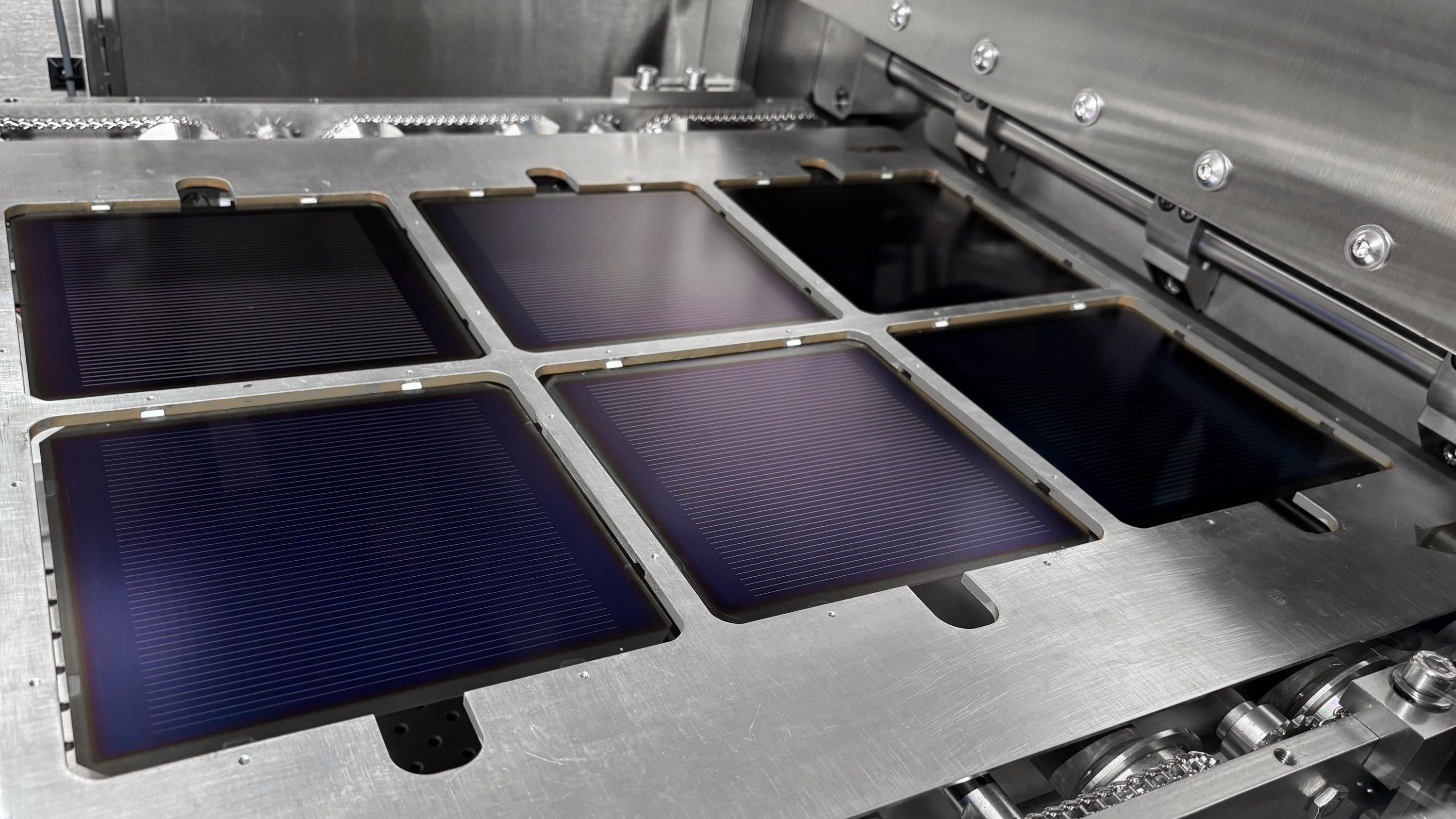

Take solar panels, for instance. They tend to last at least 25, maybe 30 years before they start to lose the ability to efficiently harness energy from the sun and transform it into electricity. So the panels available for recycling today are those that were installed over two decades ago (a relatively small fraction are ones that have been broken or need to be taken down early).

In 2000, there was a little over one gigawatt of solar power installed globally. (Yes, 2000 was nearly 25 years ago—sorry!) So today’s recycling companies are competing with each other for that relatively small amount of material. If they can hang in there, there will eventually be plenty of solar panels to go around. Over 300 gigawatts of solar power were added in 2023.

This gap is a common challenge in recycling for other technologies, too. In fact, one of the problems facing the growing number of battery recycling companies is a looming shortage of materials to recycle.

It’s important to start building infrastructure now, so we’re ready for the inevitable wave of solar panels and batteries that will eventually be ready for recycling. In the meantime, recyclers can get creative in where they’re sourcing materials. Battery recyclers today will rely on a lot of manufacturing scrap. Looking to other products can help as well—rare earth metals for EV motors and wind turbines could be partially sourced from old iPhones and laptops.

Closing the loop

Even if we weren’t seeing explosive growth for new technologies, there would be another problem: no recycling process is perfect.

The issues start at the stage of collecting old materials (think of the iPods and flip phones in your junk drawer, gathering dust), but even once material makes it to a recycling center, some will wind up in the waste because it breaks down in the process or just can’t be economically recovered.

Exactly how much material can be recovered depends on the material, the recycling process, and the economics at play. Some metals, like the silver in solar cells, might be able to reach 99% recovery or higher. Others can pose harder challenges, including the lithium in batteries—one recycler, Redwood Materials, told me last year its process can recover around 80% of the lithium from used batteries and manufacturing scrap. The rest will be lost.

I don’t mean to be a Debbie Downer. Even with imperfect recovery, recycling could help meet demand for materials in many energy technologies in the future. Recycling rare earth metals could cut mining for metals like neodymium in half, or more, by 2050.

But a robust supply of recycled materials for many climate technologies is still decades away. In the meantime, many companies are working to build options that use more widely available, cheaper alternatives. Check out my story on one startup, Niron Magnetics, which is working to build permanent magnets without rare earth metals, to see how new materials can help accelerate climate action and close the gap that recycling leaves.

Related reading

See how old batteries could help power tomorrow’s EVs in my feature story on Redwood Materials.

For more on where battery recycling might be going, check out this accompanying interview with former Tesla exec and Redwood founder JB Straubel.

Some companies are working out ways to recycle the valuable materials in solar panels.

Scientists are still trying to determine how we can best recycle wind turbine blades.

Two more things

The world’s largest EV maker is getting into the shipping business. BYD is amassing a fleet of ships to export its vehicles from China to the rest of the world. Read more about why the automaker is getting creative and what comes next in this fascinating story from my colleague Zeyi Yang.

Also, be sure to read the second part of James Temple’s blockbuster series on critical minerals. This one is a fascinating analysis that digs into how one Minnesota mine could unlock billions of dollars for EVs and batteries in the US. If you missed part one detailing what’s going on with the mine and the local community, that’s here, and you can check out my interview with James about his reporting in last week’s newsletter here.

Keeping up with climate

The world’s largest cruise ship departed on its maiden voyage last week. The whole thing is a bit of a climate fiasco. Taking a cruise can be about twice as emissions intensive as flying and staying in a hotel. (Bloomberg)

A new refinery in Georgia will churn out millions of tons of jet fuel made from plants instead of petroleum. The new facility marks a milestone for alternative jet fuels. (Canary Media)

→ While alternatives are often called “sustainable aviation fuels” or SAFs, some varieties are anything but sustainable. Here’s what you need to know about all these newfangled jet fuels. (MIT Technology Review)

China nearly quadrupled its new energy storage capacity last year. It’s a massive jump for the growing industry, which is key to balancing the growing fraction of renewables on the grid. (Bloomberg)

Huge charging depots for electric trucks are coming to California. Big batteries in big vehicles require big chargers, and new funding from the US government could be crucial in building them. (Canary Media)

→ The three biggest truck makers are calling for better charging infrastructure for heavy-duty vehicles (New York Times)

EV charging can get a bit tricky for those of us who don’t live in single-family homes with a garage to charge in. Here are some solutions. (Washington Post)

The US is the world’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas, but new exports are on pause. The Department of Energy says it’s trying to work out how to regulate them, and what the climate impact of cutting gas exports might be. (Grist)