Google Replaces Title Tags With Site Names For Homepage Results via @sejournal, @martinibuster

Google appears to have stopped showing title tags for mobile search results for the entire website such as in searches for the name of a website which generally show the home page.

This feature does not work for subdomains.

According to Google’s Search Central documentation for site names:

“Currently, Google Search supports site names from homepages at the domain-level, and not at the subdomain (for example, https://news.example.com) and or subdirectory (for example, https://example.com/news) level.”

What’s being shown in mobile searches is just the generic name for a website.

For example, a mobile search for Search Engine Journal shows a search engine results page (SERP) with the generic name of the website, Search Engine Journal.

The title tag for the above home page is:

Search Engine Journal - SEO, Search Marketing News and Tutorials

Non-branded searches for keywords appear to still show the title tags.

Brand name + keyword searches also appear to still show the title tags.

Why Is Google Using Site Names?

Google is using site names in order to make it easier for users to identify the specific website in the search results.

Google’s official announcement explained:

“Today, Search is introducing site names on mobile search results to make it easier to identify the website that’s associated with each result…”

This new feature is available in the English, French, Japanese, and German languages and will begin showing up in other languages over the next few months.

New Feature Doesn’t Always Work

A search for a compound word domain name like “Search Engine Journal” and “searchenginejournal” return the same search results that featured the new site names as the title link.

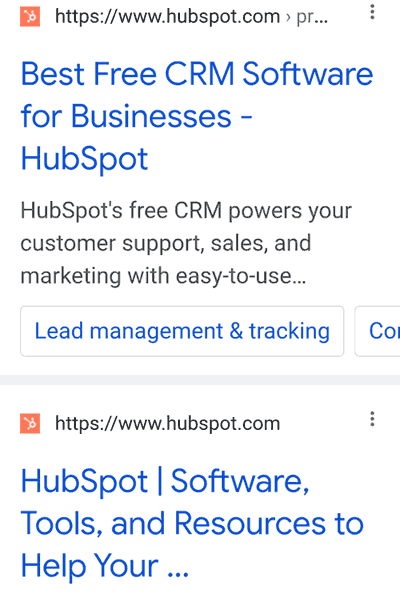

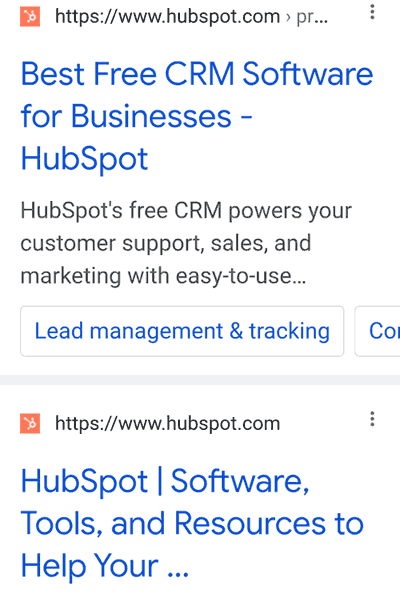

But a search using the compound word domain name HubSpot shows the old version search result with the title tags.

Search Result for Keyword Phrase “HubSpot”

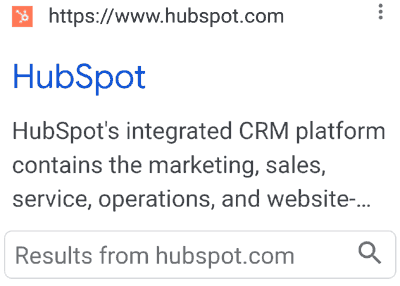

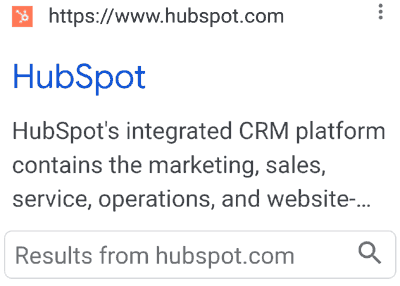

But a search for Hub Spot (with a space between the two words) does work and shows the site name.

Search Result for Keyword Phrase: “Hub Spot”

A search for compound word name “Wordfence” and “word fence” returns the same site name search.

Search Result for keywords “Wordfence” & “Word Fence”

So it appears that Google isn’t consistently returning site name results for HubSpot but is doing it correctly for many other sites.

Structured Data for New Site Names Feature

Google is recommending the use of the WebSite structured data type.

Previously the WebSite structured data site was considered pointless because obviously Google knows a website is a website and it didn’t need structured data to understand that Google was indexing a website.

But that’s changed because Google is now using the WebSite structured data type, specifically the “name” property, to understand what the site name of a website is.

Google published an example of the WebSite structured data with the “name” property in use:

Example: A Site about Examples

The above structured data must be shown on the home page.

Google’s Search Central page for site name recommends the following for placement of the WebSite structured data:

“The WebSite structured data must be on the homepage of the site.

By homepage, we mean the domain-level root URI.

For example, https://example.com is the homepage of the domain, while https://example.com/de/index.html isn’t the homepage.”

What if a Site Has an Alternate Name?

What’s useful about the WebSite structured data is that it offers the opportunity to tell Google what the alternate name of the website is.

Google explains how to do it:

“If you want to provide an alternate version of your site name (for example, an acronym or shorter name), you can do this by adding the alternateName property.

This is optional.”

The structured data for adding an optional name looks like this:

JSON Structured Data for Optional Name

Google Uses More Than Structured Data

The Google documentation on site names explains that Google is using on-page, off-page and meta data information in addition to structured data to determine what a webpage site name is.

This is what Google uses to understand the site name:

- WebSite structured data

- Title tag

- Headings (H1, H2, etc.)

- Open Graph Protocol meta data, specifically the og:site_name

Something to take note of is that og:site_name property is an optional but recommended Open Graph property.

The Open Graph notation generally looks like this in the HTML code:

Google Site Names

The new site names feature in Google search looks attractive on mobile devices.

It makes sense to have less clutter in the SERPs for home page brand name searches. although I can see some complaining about the absence of title tag influence in these kinds of searches.

Citations

Read the Official Announcement

Introducing site names on Google Search

Read the Search Central Documentation

Provide a site name to Google Search

Featured image by Shutterstock/Asier Romero