Lisa Holligan already had two children when she decided to try for another baby. Her first two pregnancies had come easily. But for some unknown reason, the third didn’t. Holligan and her husband experienced miscarriage after miscarriage after miscarriage.

Like many other people struggling to conceive, Holligan turned to in vitro fertilization, or IVF. The technology allows embryologists to take sperm and eggs and fuse them outside the body, creating embryos that can then be transferred into a person’s uterus.

The fertility clinic treating Holligan was able to create six embryos using her eggs and her husband’s sperm. Genetic tests revealed that only three of these were “genetically normal.” After the first was transferred, Holligan got pregnant. Then she experienced yet another miscarriage. “I felt numb,” she recalls. But the second transfer, which took place several months later, stuck. And little Quinn, who turns four in February, was the eventual happy result. “She is the light in our lives,” says Holligan.

Holligan, who lives in the UK, opted to donate her “genetically abnormal” embryos for scientific research. But she still has one healthy embryo frozen in storage. And she doesn’t know what to do with it.

Should she and her husband donate it to another family? Destroy it? “It’s almost four years down the line, and we still haven’t done anything with [the embryo],” she says. The clinic hasn’t been helpful—Holligan doesn’t remember talking about what to do with leftover embryos at the time, and no one there has been in touch with her for years, she says.

Holligan’s embryo is far from the only one in this peculiar limbo. Millions—or potentially tens of millions—of embryos created through IVF sit frozen in time, stored in cryopreservation tanks around the world. The number is only growing thanks to advances in technology, the rising popularity of IVF, and improvements in its success rates.

At a basic level, an embryo is simply a tiny ball of a hundred or so cells. But unlike other types of body tissue, it holds the potential for life. Many argue that this endows embryos with a special moral status, one that requires special protections. The problem is that no one can really agree on what that status is. To some, they’re human cells and nothing else. To others, they’re morally equivalent to children. Many feel they exist somewhere between those two extremes.

There are debates, too, over how we should classify embryos in law. Are they property? Do they have a legal status? These questions are important: There have been multiple legal disputes over who gets to use embryos, who is responsible if they are damaged, and who gets the final say over their fate. And the answers will depend not only on scientific factors, but also on ethical, cultural, and religious ones.

The options currently available to people with leftover IVF embryos mirror this confusion. As a UK resident, Holligan can choose to discard her embryos, make them available to other prospective parents, or donate them for research. People in the US can also opt for “adoption,” “placing” their embryos with families they get to choose. In Germany, people are not typically allowed to freeze embryos at all. And in Italy, embryos that are not used by the intended parents cannot be discarded or donated. They must remain frozen, ostensibly forever.

While these embryos persist in suspended animation, patients, clinicians, embryologists, and legislators must grapple with the essential question of what we should do with them. What do these embryos mean to us? Who should be responsible for them?

Meanwhile, many of these same people are trying to find ways to bring down the total number of embryos in storage. Maintenance costs are high. Some clinics are running out of space. And with a greater number of embryos in storage, there are more opportunities for human error. They are grappling with how to get a handle on the growing number of embryos stuck in storage with nowhere to go.

The embryo boom

There are a few reasons why this has become such a conundrum. And they largely come down to an increasing demand for IVF and improvements in the way it is practiced. “It’s a problem of our own creation,” says Pietro Bortoletto, a reproductive endocrinologist at Boston IVF in Massachusetts. IVF has only become as successful as it is today by “generating lots of excess eggs and embryos along the way,” he says.

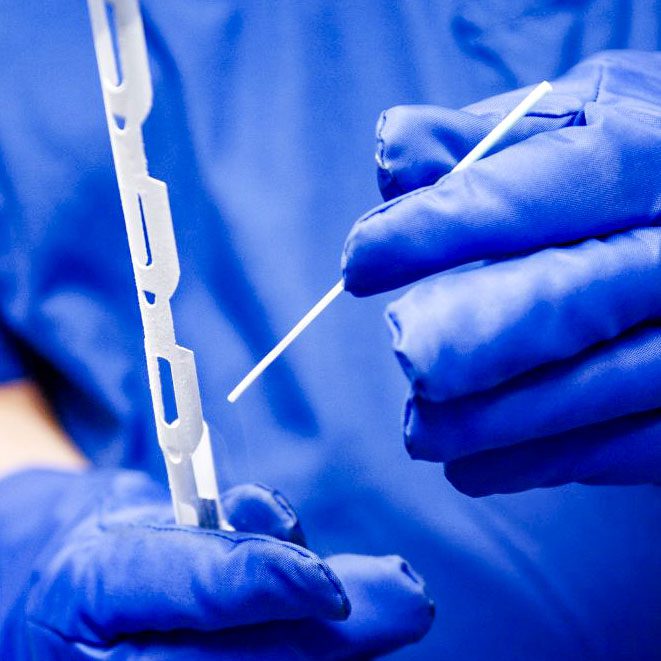

To have the best chance of creating healthy embryos that will attach to the uterus and grow in a successful pregnancy, clinics will try to collect multiple eggs. People who undergo IVF will typically take a course of hormone injections to stimulate their ovaries. Instead of releasing a single egg that month, they can expect to produce somewhere between seven and 20 eggs. These eggs can be collected via a needle that passes through the vagina and into the ovaries. The eggs are then taken to a lab, where they are introduced to sperm. Around 70% to 80% of IVF eggs are successfully fertilized to create embryos.

The embryos are then grown in the lab. After around five to seven days an embryo reaches a stage of development at which it is called a blastocyst, and it is ready to be transferred to a uterus. Not all IVF embryos reach this stage, however—only around 30% to 50% of them make it to day five. This process might leave a person with no viable embryos. It could also result in more than 10, only one of which is typically transferred in each pregnancy attempt. In a typical IVF cycle, one embryo might be transferred to the person’s uterus “fresh,” while any others that were created are frozen and stored.

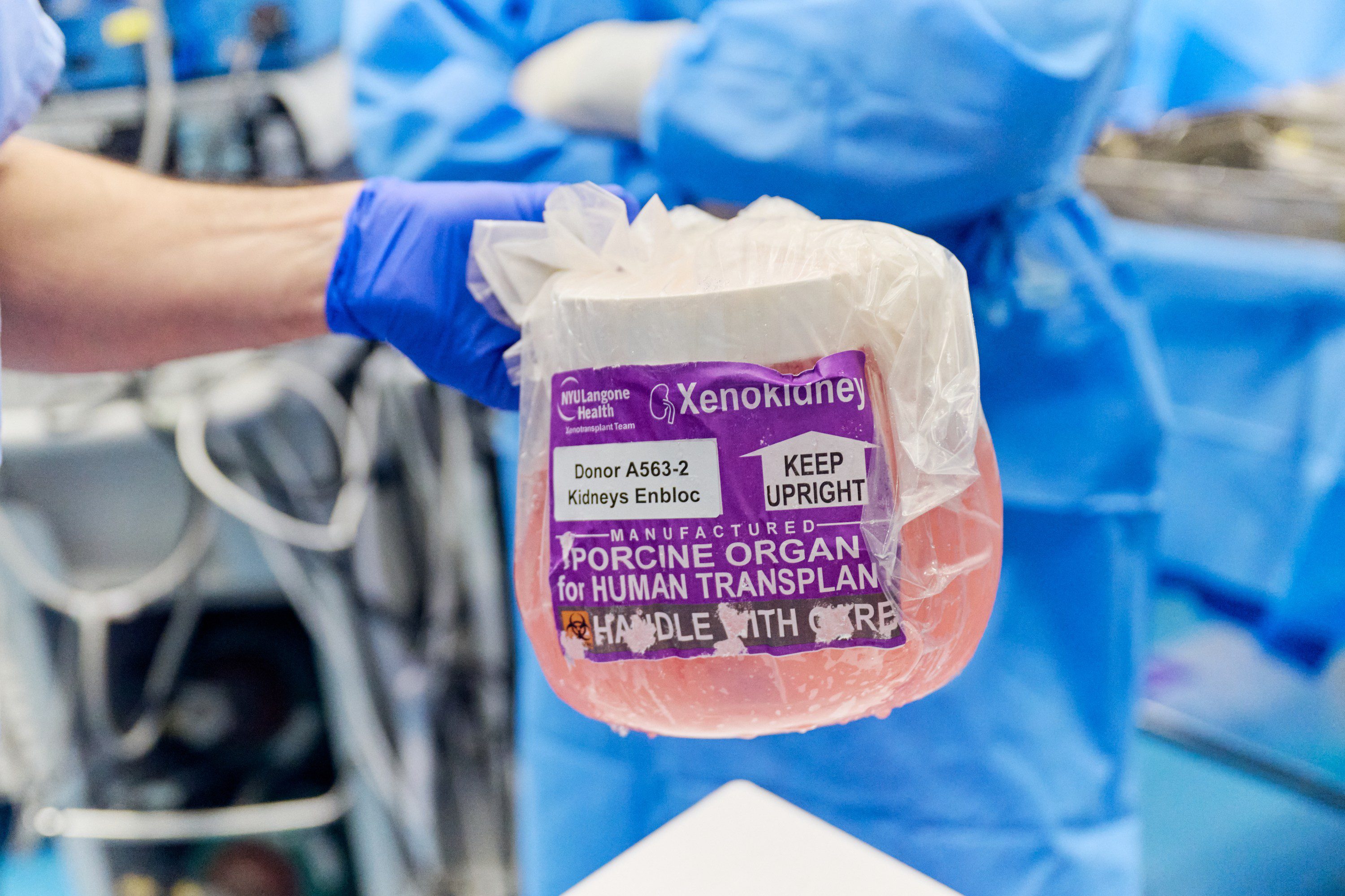

IVF success rates have increased over time, in large part thanks to improvements in this storage technology. A little over a decade ago, embryologists tended to use a “slow freeze” technique, says Bortoletto, and many embryos didn’t survive the process. Embryos are now vitrified instead, using liquid nitrogen to rapidly cool them from room temperature to -196 °C in less than two seconds. Vitrification essentially turns all the water in the embryos into a glasslike state, avoiding the formation of damaging ice crystals.

Now, clinics increasingly take a “freeze all” approach, in which they cryopreserve all the viable embryos and don’t start transferring them until later. In some cases, this is so that the clinic has a chance to perform genetic tests on the embryo they plan to transfer.

Once a lab-grown embryo is around seven days old, embryologists can remove a few cells for preimplantation genetic testing (PGT), which screens for genetic factors that might make healthy development less likely or predispose any resulting children to genetic diseases. PGT is increasingly popular in the US—in 2014, it was used in 13% of IVF cycles, but by 2016, that figure had increased to 27%. Embryos that undergo PGT have to be frozen while the tests are run, which typically takes a week or two, says Bortoletto: “You can’t continue to grow them until you get those results back.”

And there doesn’t seem to be a limit to how long an embryo can stay in storage. In 2022, a couple in Oregon had twins who developed from embryos that had been frozen for 30 years.

Put this all together, and it’s easy to see how the number of embryos in storage is rocketing. We’re making and storing more embryos than ever before. When you combine that with the growing demand for IVF, which is increasing in use by the year, perhaps it’s not surprising that the number of embryos sitting in storage tanks is estimated to be in the millions.

I say estimated, because no one really knows how many there are. In 2003, the results of a survey of fertility clinics in the US suggested that there were around 400,000 in storage. Ten years later, in 2013, another pair of researchers estimated that, in total, around 1.4 million embryos had been cryopreserved in the US. But Alana Cattapan, now a political scientist at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada, and her colleagues found flaws in the study and wrote in 2015 that the number could be closer to 4 million.

That was a decade ago. When I asked embryologists what they thought the number might be in the US today, I got responses between 1 million and 10 million. Bortoletto puts it somewhere around 5 million.

Globally, the figure is much higher. There could be tens of millions of embryos, invisible to the naked eye, kept in a form of suspended animation. Some for months, years, or decades. Others indefinitely.

Stuck in limbo

In theory, people who have embryos left over from IVF have a few options for what to do with them. They could donate the embryos for someone else to use. Often this can be done anonymously (although genetic tests might later reveal the biological parents of any children that result). They could also donate the embryos for research purposes. Or they could choose to discard them. One way to do this is to expose the embryos to air, causing the cells to die.

Studies suggest that around 40% of people with cryopreserved embryos struggle to make this decision, and that many put it off for five years or more. For some people, none of the options are appealing.

In practice, too, the available options vary greatly depending on where you are. And many of them lead to limbo.

Take Spain, for example, which is a European fertility hub, partly because IVF there is a lot cheaper than in other Western European countries, says Giuliana Baccino, managing director of New Life Bank, a storage facility for eggs and sperm in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and vice chair of the European Fertility Society. Operating costs are low, and there’s healthy competition—there are around 330 IVF clinics operating in Spain. (For comparison, there are around 500 IVF clinics in the US, which has a population almost seven times greater.)

Baccino, who is based in Madrid, says she often hears of foreign patients in their late 40s who create eight or nine embryos for IVF in Spain but end up using only one or two of them. They go back to their home countries to have their babies, and the embryos stay in Spain, she says. These individuals often don’t come back for their remaining embryos, either because they have completed their families or because they age out of IVF eligibility (Spanish clinics tend not to offer the treatment to people over 50).

In 2023, the Spanish Fertility Society estimated that there were 668,082 embryos in storage in Spain, and that around 60,000 of them were “in a situation of abandonment.” In these cases the clinics might not be able to reach the intended parents, or might not have a clear directive from them, and might not want to destroy any embryos in case the patients ask for them later. But Spanish clinics are wary of discarding embryos even when they have permission to do so, says Baccino. “We always try to avoid trouble,” she says. “And we end up with embryos in this black hole.”

This happens to embryos in the US, too. Clinics can lose touch with their patients, who may move away or forget about their remaining embryos once they have completed their families. Other people may put off making decisions about those embryos and stop communicating with the clinic. In cases like these, clinics tend to hold onto the embryos, covering the storage fees themselves.

Nowadays clinics ask their patients to sign contracts that cover long-term storage of embryos—and the conditions of their disposal. But even with those in hand, it can be easier for clinics to leave the embryos in place indefinitely. “Clinics are wary of disposing of them without explicit consent, because of potential liability,” says Cattapan, who has researched the issue. “People put so much time, energy, money into creating these embryos. What if they come back?”

Bortoletto’s clinic has been in business for 35 years, and the handful of sites it operates in the US have a total of over 47,000 embryos in storage, he says. “Our oldest embryo in storage was frozen in 1989,” he adds.

Some people may not even know where their embryos are. Sam Everingham, who founded and directs Growing Families, an organization offering advice on surrogacy and cross-border donations, traveled with his partner from their home in Melbourne, Australia, to India to find an egg donor and surrogate back in 2009. “It was a Wild West back then,” he recalls. Everingham and his partner used donor eggs to create eight embryos with their sperm.

Everingham found the experience of trying to bring those embryos to birth traumatic. Baby Zac was stillborn. Baby Ben died at seven weeks. “We picked ourselves up and went again,” he recalls. Two embryo transfers were successful, and the pair have two daughters today.

But the fate of the rest of their embryos is unclear. India’s government decided to ban commercial surrogacy for foreigners in 2015, and Everingham lost track of where they are. He says he’s okay with that. As far as he’s concerned, those embryos are just cells.

He knows not everyone feels the same way. A few days before we spoke, Everingham had hosted a couple for dinner. They had embryos in storage and couldn’t agree on what to do with them. “The mother … wanted them donated to somebody,” says Everingham. Her husband was very uncomfortable with the idea. “[They have] paid storage fees for 14 years for those embryos because neither can agree on what to do with them,” says Everingham. “And this is a very typical scenario.”

Lisa Holligan’s experience is similar. Holligan thought she’d like to donate her last embryo to another person—someone else who might have been struggling to conceive. “But my husband and I had very different views on it,” she recalls. He saw the embryo as their child and said he wouldn’t feel comfortable with giving it up to another family. “I started having these thoughts about a child coming to me when they’re older, saying they’ve had a terrible life, and [asking] ‘Why didn’t you have me?’” she says.

After all, her daughter Quinn began as an embryo that was in storage for months. “She was frozen in time. She could have been frozen for five years like [the leftover] embryo and still be her,” she says. “I know it sounds a bit strange, but this embryo could be a child in 20 years’ time. The science is just mind-blowing, and I think I just block it out. It’s far too much to think about.”

No choice at all

Choosing the fate of your embryos can be difficult. But some people have no options at all.

This is the case in Italy, where the laws surrounding assisted reproductive technology have grown increasingly restrictive. Since 2004, IVF has been accessible only to heterosexual couples who are either married or cohabiting. Surrogacy has also been prohibited in the country for the last 20 years, and in 2024, it was made a “universal crime.” The move means Italians can be prosecuted for engaging in surrogacy anywhere in the world, a position Italy has also taken on the crimes of genocide and torture, says Sara Dalla Costa, a lawyer specializing in assisted reproduction and an IVF clinic manager at Instituto Bernabeu on the outskirts of Venice.

The law surrounding leftover embryos is similarly inflexible. Dalla Costa says there are around 900,000 embryos in storage in Italy, basing the estimate on figures published in 2021 and the number of IVF cycles performed since then. By law, these embryos cannot be discarded. They cannot be donated to other people, and they cannot be used for research.

Even when genetic tests show that the embryo has genetic features making it “incompatible with life,” it must remain in storage, forever, says Dalla Costa.

“There are a lot of patients that want to destroy embryos,” she says. For that, they must transfer their embryos to Spain or other countries where it is allowed.

Even people who want to use their embryos may “age out” of using them. Dalla Costa gives the example of a 48-year-old woman who undergoes IVF and creates five embryos. If the first embryo transfer happens to result in a successful pregnancy, the other four will end up in storage. Once she turns 50, this woman won’t be eligible for IVF in Italy. Her remaining embryos become stuck in limbo. “They will be stored in our biobanks forever,” says Dalla Costa.

Dalla Costa says she has “a lot of examples” of couples who separate after creating embryos together. For many of them, the stored embryos become a psychological burden. With no way of discarding them, these couples are forever connected through their cryopreserved cells. “A lot of our patients are stressed for this reason,” she says.

Earlier this year, one of Dalla Costa’s clients passed away, leaving behind the embryos she’d created with her husband. He asked the clinic to destroy them. In cases like these, Dalla Costa will contact the Italian Ministry of Health. She has never been granted permission to discard an embryo, but she hopes that highlighting cases like these might at least raise awareness about the dilemmas the country’s policies are creating for some people.

Snowflakes and embabies

In Italy, embryos have a legal status. They have protected rights and are viewed almost as children. This sentiment isn’t specific to Italy. It is shared by plenty of individuals who have been through IVF. “Some people call them ‘embabies’ or ‘freezer babies,’” says Cattapan.

It is also shared by embryo adoption agencies in the US. Beth Button is executive director of one such program, called Snowflakes—a division of Nightlight Christian Adoptions agency, which considers cryopreserved embryos to be children, frozen in time, waiting to be born. Snowflakes matches embryo donors, or “placing families,” with recipients, termed “adopting families.” Both parties share their information and essentially get to choose who they donate to or receive from. By the end of 2024, 1,316 babies had been born through the Snowflakes embryo adoption program, says Button.

Button thinks that far too many embryos are being created in IVF labs around the US. Around 10 years ago, her agency received a donation from a couple that had around 38 leftover embryos to donate. “We really encourage [people with leftover embryos in storage] to make a decision [about their fate], even though it’s an emotional, difficult decision,” she says. “Obviously, we just try to keep [that discussion] focused on the child,” she says. “Is it better for these children to be sitting in a freezer, even though that might be easier for you, or is it better for them to have a chance to be born into a loving family? That kind of pushes them to the point where they’re ready to make that decision.”

Button and her colleagues feel especially strongly about embryos that have been in storage for a long time. These embryos are usually difficult to place, because they are thought to be of poorer quality, or less likely to successfully thaw and result in a healthy birth. The agency runs a program called Open Hearts specifically to place them, along with others that are harder to match for various reasons. People who accept one but fail to conceive are given a shot with another embryo, free of charge.

“We have seen perfectly healthy children born from very old embryos, [as well as] embryos that were considered such poor quality that doctors didn’t even want to transfer them,” says Button. “Right now, we have a couple who is pregnant with [an embryo] that was frozen for 30 and a half years. If that pregnancy is successful, that will be a record for us, and I think it will be a worldwide record as well.”

Many embryologists bristle at the idea of calling an embryo a child, though. “Embryos are property. They are not unborn children,” says Bortoletto. In the best case, embryos create pregnancies around 65% of the time, he says. “They are not unborn children,” he repeats.

Person or property?

In 2020, an unauthorized person allegedly entered an IVF clinic in Alabama and pulled frozen embryos from storage, destroying them. Three sets of intended parents filed suit over their “wrongful death.” A trial court dismissed the claims, but the Alabama Supreme Court disagreed, essentially determining that those embryos were people. The ruling shocked many and was expected to have a chilling effect on IVF in the state, although within a few weeks, the state legislature granted criminal and civil immunity to IVF clinics.

But the Alabama decision is the exception. While there are active efforts in some states to endow embryos with the same legal rights as people, a move that could potentially limit access to abortion, “most of the [legal] rulings in this area have made it very clear that embryos are not people,” says Rich Vaughn, an attorney specializing in fertility law and the founder of the US-based International Fertility Law Group. At the same time, embryos are not just property. “They’re something in between,” says Vaughn. “They’re sort of a special type of property.”

UK law takes a similar approach: The language surrounding embryos and IVF was drafted with the idea that the embryo has some kind of “special status,” although it was never made entirely clear exactly what that special status is, says James Lawford Davies, a solicitor and partner at LDMH Partners, a law firm based in York, England, that specializes in life sciences. Over the years, the language has been tweaked to encompass embryos that might arise from IVF, cloning, or other means; it is “a bit of a fudge,” says Lawford Davies. Today, the official—if somewhat circular—legal definition in the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act reads: “embryo means a live human embryo.”

And while people who use their eggs or sperm to create embryos might view these embryos as theirs, according to UK law, embryos are more like “a stateless bundle of cells,” says Lawford Davies. They’re not quite property—people don’t own embryos. They just have control over how they are used.

Many legal disputes revolve around who has control. This was the experience of Natallie Evans, who created embryos with her then partner Howard Johnston in the UK in 2001. The couple separated in 2002. Johnston wrote to the clinic to ask that their embryos be destroyed. But Evans, who had been diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2001, wanted to use them. She argued that Johnston had already consented to their creation, storage, and use and should not be allowed to change his mind. The case eventually made it to the European Court of Human Rights, and Evans lost. The case set a precedent that consent was key and could be withdrawn at any time.

In Italy, on the other hand, withdrawing consent isn’t always possible. In 2021, a case like Natallie Evans’s unfolded in the Italian courts: A woman who wanted to proceed with implantation after separating from her partner went to court for authorization. “She said that it was her last chance to be a mother,” says Dalla Costa. The judge ruled in her favor.

Dalla Costa’s clinics in Italy are now changing their policies to align with this decision. Male partners must sign a form acknowledging that they cannot prevent embryos from being used once they’ve been created.

The US situation is even more complicated, because each state has its own approach to fertility regulation. When I looked through a series of published legal disputes over embryos, I found little consistency—sometimes courts ruled to allow a woman to use an embryo without the consent of her former partner, and sometimes they didn’t. “Some states have comprehensive … legislation; some do not,” says Vaughn. “Some have piecemeal legislation, some have only case law, some have all of the above, some have none of the above.”

The meaning of an embryo

So how should we define an embryo? “It’s the million-dollar question,” says Heidi Mertes, a bioethicist at Ghent University in Belgium. Some bioethicists and legal scholars, including Vaughn, think we’d all stand to benefit from clear legal definitions.

Risa Cromer, a cultural anthropologist at Purdue University in Indiana, who has spent years researching the field, is less convinced. Embryos exist in a murky, in-between state, she argues. You can (usually) discard them, or transfer them, but you can’t sell them. You can make claims against damages to them, but an embryo is never viewed in the same way as a car, for example. “It doesn’t fit really neatly into that property category,” says Cromer. “But, very clearly, it doesn’t fit neatly into the personhood category either.”

And there are benefits to keeping the definition vague, she adds: “There is, I think, a human need for there to be a wide range of interpretive space for what IVF embryos are or could be.”

That’s because we don’t have a fixed moral definition of what an embryo is. Embryos hold special value even for people who don’t view them as children. They hold potential as human life. They can come to represent a fertility journey—one that might have been expensive, exhausting, and traumatizing. “Even for people who feel like they’re just cells, it still cost a lot of time, money, [and effort] to get those [cells],” says Cattapan.

“I think it’s an illusion that we might all agree on what the moral status of an embryo is,” Mertes says.

In the meantime, a growing number of embryologists, ethicists, and researchers are working to persuade fertility clinics and their patients not to create or freeze so many embryos in the first place. Early signs aren’t promising, says Baccino. The patients she has encountered aren’t particularly receptive to the idea. “They think, ‘If I will pay this amount for a cycle, I want to optimize my chances, so in my case, no,’” she says. She expects the number of embryos in storage to continue to grow.

Holligan’s embryo has been in storage for almost five years. And she still doesn’t know what to do with it. She tears up as she talks through her options. Would discarding the embryo feel like a miscarriage? Would it be a sad thing? If she donated the embryo, would she spend the rest of her life wondering what had become of her biological child, and whether it was having a good life? Should she hold on to the embryo for another decade in case her own daughter needs to use it at some point?

“The question [of what to do with the embryo] does pop into my head, but I quickly try to move past it and just say ‘Oh, that’s something I’ll deal with at a later time,’” says Holligan. “I’m sure [my husband] does the same.”

The accumulation of frozen embryos is “going to continue this way for some time until we come up with something that fully addresses everyone’s concerns,” says Vaughn. But will we ever be able to do that?

“I’m an optimist, so I’m gonna say yes,” he says with a hopeful smile. “But I don’t know at the moment.”