In 2016, I attended a large meeting of journalists in Washington, DC. The keynote speaker was Jennifer Doudna, who just a few years before had co-invented CRISPR, a revolutionary method of changing genes that was sweeping across biology labs because it was so easy to use. With its discovery, Doudna explained, humanity had achieved the ability to change its own fundamental molecular nature. And that capability came with both possibility and danger. One of her biggest fears, she said, was “waking up one morning and reading about the first CRISPR baby”—a child with deliberately altered genes baked in from the start.

As a journalist specializing in genetic engineering—the weirder the better—I had a different fear. A CRISPR baby would be a story of the century, and I worried some other journalist would get the scoop. Gene editing had become the biggest subject on the biotech beat, and once a team in China had altered the DNA of a monkey to introduce customized mutations, it seemed obvious that further envelope-pushing wasn’t far off.

If anyone did create an edited baby, it would raise moral and ethical issues, among the profoundest of which, Doudna had told me, was that doing so would be “changing human evolution.” Any gene alterations made to an embryo that successfully developed into a baby would get passed on to any children of its own, via what’s known as the germline. What kind of scientist would be bold enough to try that?

Two years and nearly 8,000 miles in an airplane seat later, I found the answer. At a hotel in Guangzhou, China, I joined a documentary film crew for a meeting with a biophysicist named He Jiankui, who appeared with a retinue of advisors. During the meeting, He was immensely gregarious and spoke excitedly about his research on embryos of mice, monkeys, and humans, and about his eventual plans to improve human health by adding beneficial genes to people’s bodies from birth. Still imagining that such a step must lie at least some way off, I asked if the technology was truly ready for such an undertaking.

“Ready,” He said. Then, after a laden pause: “Almost ready.”

Why wait 100,000 years for natural selection to do its job? For a few hundred dollars in chemicals, you could try to install these changes in an embryo in 10 minutes.

Four weeks later, I learned that he’d already done it, when I found data that He had placed online describing the genetic profiles of two gene-edited human fetuses—that is, ”CRISPR babies” in gestation—as well an explanation of his plan, which was to create humans immune to HIV. He had targeted a gene called CCR5, which in some people has a variation known to protect against HIV infection. It’s rare for numbers in a spreadsheet to make the hair on your arms stand up, although maybe some climatologists feel the same way seeing the latest Arctic temperatures. It appeared that something historic—and frightening—had already happened. In our story breaking the news that same day, I ventured that the birth of genetically tailored humans would be something between a medical breakthrough and the start of a slippery slope of human enhancement.

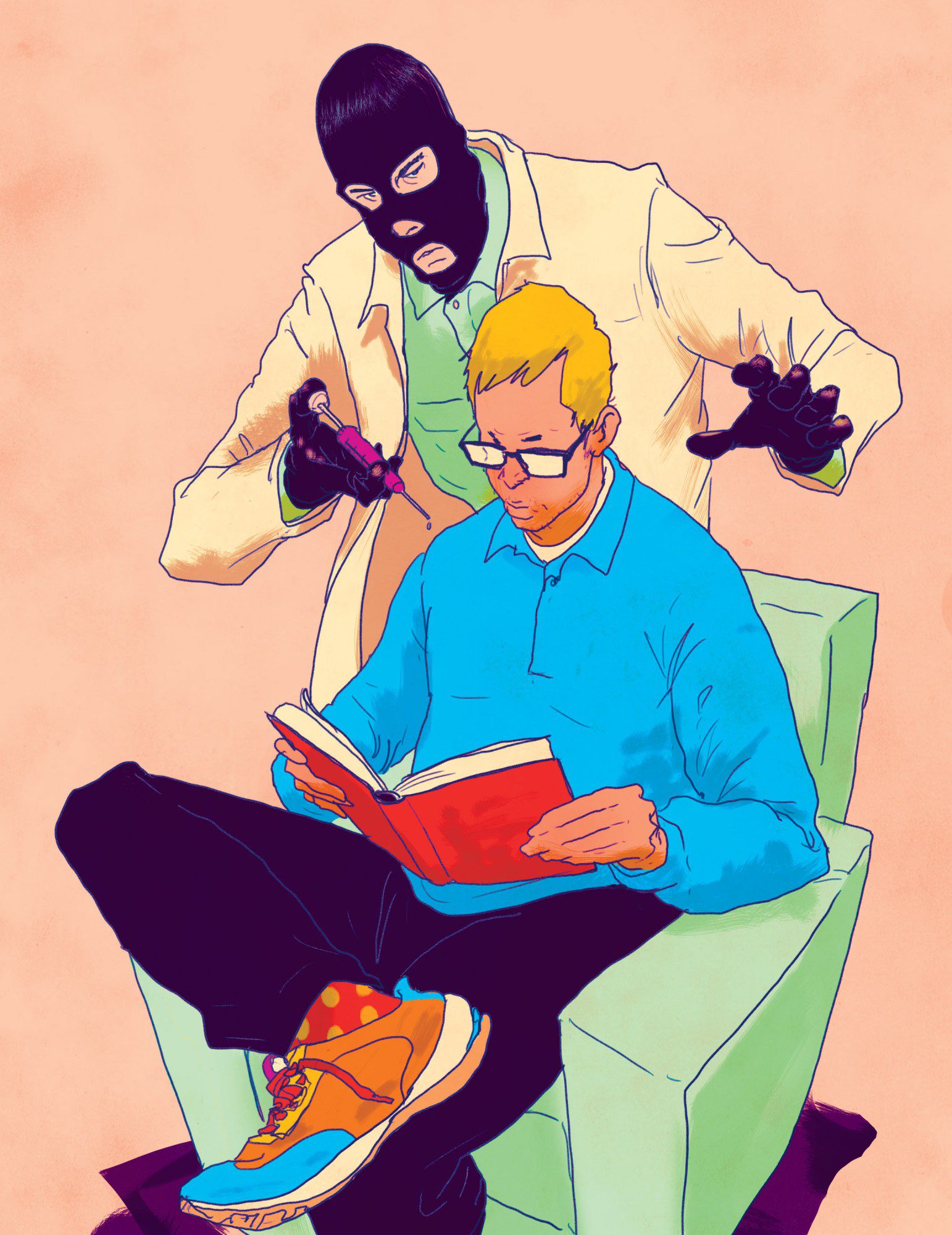

For his actions, He was later sentenced to three years in prison, and his scientific practices were roundly excoriated. The edits he made, on what proved to be twin girls (and a third baby, revealed later), had in fact been carelessly imposed, almost in an out-of-control fashion, according to his own data. And I was among a flock of critics—in the media and academia—who would subject He and his circle of advisors to Promethean-level torment via a daily stream of articles and exposés. Just this spring, Fyodor Urnov, a gene-editing specialist at the University of California, Berkeley, lashed out on X, calling He a scientific “pyromaniac” and comparing him to a Balrog, a demon from J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. It could seem as if He’s crime wasn’t just medical wrongdoing but daring to take the wheel of the very processes that brought you, me, and him into being.

Futurists who write about the destiny of humankind have imagined all sorts of changes. We’ll all be given auxiliary chromosomes loaded with genetic goodies, or maybe we’ll march through life as a member of a pod of identical clones. Perhaps sex will become outdated as we reproduce exclusively through our stem cells. Or human colonists on another planet will be isolated so long that they become their own species. The thing about He’s idea, though, is that he drew it from scientific realities close at hand. Just as some gene mutations cause awful, rare diseases, others are being discovered that lend a few people the ability to resist common ones, like diabetes, heart disease, Alzheimer’s—and HIV. Such beneficial, superpower-like traits might spread to the rest of humanity, given enough time. But why wait 100,000 years for natural selection to do its job? For a few hundred dollars in chemicals, you could try to install these changes in an embryo in 10 minutes. That is, in theory, the easiest way to go about making such changes—it’s just one cell to start with.

Editing human embryos is restricted in much of the world—and making an edited baby is flatly illegal in most countries surveyed by legal scholars. But advancing technology could render the embryo issue moot. New ways of adding CRISPR to the bodies of people already born—children and adults—could let them easily receive changes as well. Indeed, if you are curious what the human genome could look like in 125 years, it’s possible that many people will be the beneficiaries of multiple rare, but useful, gene mutations currently found in only small segments of the population. These could protect us against common diseases and infections, but eventually they could also yield frank improvements in other traits, such as height, metabolism, or even cognition. These changes would not be passed on genetically to people’s offspring, but if they were widely distributed, they too would become a form of human-directed self-evolution—easily as big a deal as the emergence of computer intelligence or the engineering of the physical world around us.

I was surprised to learn that even as He’s critics take issue with his methods, they see the basic stratagem as inevitable. When I asked Urnov, who helped coin the term “genome editing” in 2005, what the human genome could be like in, say, a century, he readily agreed that improvements using superpower genes will probably be widely introduced into adults—and embryos—as the technology to do so improves. But he warned that he doesn’t necessarily trust humanity to do things the right way. Some groups will probably obtain the health benefits before others. And commercial interests could eventually take the trend in unhelpful directions—much as algorithms keep his students’ noses pasted, unnaturally, to the screens of their mobile phones. “I would say my enthusiasm for what the human genome is going to be in 100 years is tempered by our history of a lack of moderation and wisdom,” he said. “You don’t need to be Aldous Huxley to start writing dystopias.”

Editing early

At around 10 p.m. Beijing time, He’s face flicked into view over the Tencent videoconferencing app. It was May 2024, nearly six years after I had first interviewed him, and he appeared in a loftlike space with a soaring ceiling and a wide-screen TV on a wall. Urnov had warned me not to speak with He, since it would be like asking “Bernie Madoff to opine about ethical investing.” But I wanted to speak to him, because he’s still one of the few scientists willing to promote the idea of broad improvements to humanity’s genes.

Of course, it’s his fault everyone is so down on the idea. After his experiment, China formally made “implantation” of gene-edited human embryos into the uterus a crime. Funding sources evaporated. “He created this blowback, and it brought to a halt many people’s research. And there were not many to begin with,” says Paula Amato, a fertility doctor at Oregon Health and Science University who co-leads one of only two US teams that have ever reported editing human embryos in a lab. “And the publicity—nobody wants to be associated with something that is considered scandalous or eugenic.”

After leaving prison in 2022, the Chinese biophysicist surprised nearly everyone by seeking to make a scientific comeback. At first, he floated ideas for DNA-based data storage and “affordable” cures for children who have muscular dystrophy. But then, in summer 2023, he posted to social media that he intended to return to research on how to change embryos with gene editing, with the caveat that “no human embryo will be implanted for pregnancy.” His new interest was a gene called APP, or amyloid precursor protein. It’s known that people who possess a very rare version, or “allele,” of this gene almost never develop Alzheimer’s disease.

In our video call, He said the APP gene is the main focus of his research now and that he is determining how to change it. The work, he says, is not being conducted on human embryos, but rather on mice and on kidney cells, using an updated form of CRISPR called base editing, which can flip individual letters of DNA without breaking the molecule.

“We just want to expand the protective allele from small amounts of lucky people to maybe most people,” He told me. And if you made the adjustment at the moment an egg is fertilized, you would only have to change one cell in order for the change to take hold in the embryo and, eventually, everywhere in a person’s brain. Trying to edit an individual’s brain after birth “is as hard a delivering a person to the moon,” He said. “But if you deliver gene editing to an embryo, it’s as easy as driving home.”

In the future, He said, human embryos will “obviously” be corrected for all severe genetic diseases. But they will also receive “a panel” of “perhaps 20 or 30” edits to improve health. (If you’ve seen the sci-fi film Gattaca, it takes place in a world where such touch-ups are routine—leading to stigmatization of the movie’s hero, a would-be space pilot who lacks them.) One of these would be to install the APP variant, which involves changing a single letter of DNA. Others would protect against diabetes, and maybe cancer and heart disease. He calls these proposed edits “genetic vaccines” and believes people in the future “won’t have to worry” about many of the things most likely to kill them today.

Is He the person who will bring about this future? Last year, in what seemed to be a step toward his rehabilitation, he got a job heading a gene center at Wuchang University of Technology, a third-tier institution in Wuhan. But He said during our call that he had already left the position. He didn’t say what had caused the split but mentioned that a flurry of press coverage had “made people feel pressured.” One item, in a French financial paper, Les Echos, was titled “GMO babies: The secrets of a Chinese Frankenstein.” Now he carries out research at his own private lab, he says, with funding from Chinese and American supporters. He has early plans for a startup company. Could he tell me names and locations? “Of course not,” he said with a chuckle.

It could be there is no lab, just a concept. But it’s a concept that is hard to dismiss. Would you give your child a gene tweak—a swap of a single genetic letter among the 3 billion that run the length of the genome—to prevent Alzheimer’s, the mind thief that’s the seventh-leading cause of death in the US? Polls find that the American public is about evenly split on the ethics of adding disease resistance traits to embryos. A sizable minority, though, would go further. A 2023 survey published in Science found that nearly 30% of people would edit an embryo if it enhanced the resulting child’s chance of attending a top-ranked college.

The benefits of the genetic variant He claims to be working with were discovered by the Icelandic gene-hunting company deCode Genetics. Twenty-six years ago, in 1998, its founder, a doctor named Kári Stefánsson, got the green light to obtain medical records and DNA from Iceland’s citizens, allowing deCode to amass one of the first large national gene databases. Several similar large biobanks now operate, including one in the United Kingdom, which recently finished sequencing the genomes of 500,000 volunteers. These biobanks make it possible to do computerized searches to find relationships between people’s genetic makeup and real-life differences like how long they live, what diseases they get, and even how much beer they drink. The result is a statistical index of how strongly every possible difference in human DNA affects every trait that can be measured.

In 2012, deCode’s geneticists used the technique to study a tiny change in the APP gene and determined that the individuals who had it rarely developed Alzheimer’s. They otherwise seemed healthy. In fact, they seemed particularly sharp in old age and appeared to live longer, too. Lab tests confirmed that the change reduces the production of brain plaques, the abnormal clumps of protein that are a hallmark of the disease.

“This is beginning to be about the essence of who we are as a species.”

Kári Stefánsson, founder and CEO, deCode genetics

One way evolution works is when a small change or error appears in one baby’s DNA. If the change helps that person survive and reproduce, it will tend to become more common in the species—eventually, over many generations, even universal. This process is slow, but it’s visible to science. In 2018, for example, researchers determined that the Bajau, a group indigenous to Indonesia whose members collect food by diving, possess genetic changes associated with bigger spleens. This allows them to store more oxygenated red blood cells—an advantage in their lives.

Even though the variation in the APP gene seems hugely beneficial, it’s a change that benefits old people, way past their reproductive years. So it’s not the kind of advantage natural selection can readily act on. But we could act on it. That is what technology-assisted evolution would look like—seizing on a variation we think is useful and spreading it. “The way, probably, that enhancement will be done will be to look at the population, look at people who have enhanced capabilities—whatever those might be,” the Israeli medical geneticist Ephrat Levy-Lahad said during a gene-editing summit last year. “You are going to be using variations that already exist in the population that you already have information on.”

One advantage of zeroing in on advantageous DNA changes that already exist in the population is that their effects are pretested. The people located by deCode were in their 80s and 90s. There didn’t seem to be anything different about them—except their unusually clear minds. Their lives—as seen from the computer screens of deCode’s biobank—served as a kind of long-term natural experiment. Yet scientists could not be fully confident placing this variant into an embryo, since the benefits or downsides might differ depending on what other genetic factors are already present, especially other Alzheimer’s risk genes. And it would be difficult to run a study to see what happens. In the case of APP, it would take 70 years for the final evidence to emerge. By that time, the scientists involved would all be dead.

When I spoke with Stefánsson last year, he made the case both for and against altering genomes with “rare variants of large effect,” like the change in APP. “All of us would like to keep our marbles until we die. There is no question about it. And if you could, by pushing a button, install the kind of protection people with this mutation have, that would be desirable,” he said. But even if the technology to make this edit before birth exists, he says, the risks of doing so seem almost impossible to gauge: “You are not just affecting the person, but all their descendants forever. These are mutations that would allow for further selection and further evolution, so this is beginning to be about the essence of who we are as a species.”

Editing everyone

Some genetic engineers believe that editing embryos, though in theory easy to do, will always be held back by these grave uncertainties. Instead, they say, DNA editing in living adults could become easy enough to be used not only to correct rare diseases but to add enhanced capabilities to those who seek them. If that happens, editing for improvement could spread just as quickly as any consumer technology or medical fad. “I don’t think it’s going to be germline,” says George Church, a Harvard geneticist often sought out for his prognostications. “The 8 billion of us who are alive kind of constitute the marketplace.” For several years, Church has been circulating what he calls “my famous, or infamous, table of enhancements.” It’s a tally of gene variants that lend people superpowers, including APP and another that leads to extra-hard bones, which was found in a family that complained of not being able to stay afloat in swimming pools. The table is infamous because some believe Church’s inclusion of the HIV-protective CCR5 variant inspired He’s effort to edit it into the CRISPR babies.

Church believes novel gene treatments for very serious diseases, once proven, will start leading the way toward enhancements and improvements to people already born. “You’d constantly be tweaking and getting feedback,” he says—something that’s hard to do with the germline, since humans take so long to grow up. Changes to adult bodies would not be passed down, but Church thinks they could easily count as a form of heredity. He notes that railroads, eyeglasses, cell phones—and the knowledge of how to make and use all these technologies—are already all transmitted between generations. “We’re clearly inheriting even things that are inorganic,” he says.

The biotechnology industry is already finding ways to emulate the effects of rare, beneficial variants. A new category of heart drugs, for instance, mimics the effect of a rare variation in a gene, called PCSK9, that helps maintain cholesterol levels. The variation, initially discovered in a few people in the US and Zimbabwe, blocks the gene’s activity and gives them ultra-low cholesterol levels for life. The drugs, taken every few weeks or months, work by blocking the PCSK9 protein. One biotech company, though, has started trying to edit the DNA of people’s liver cells (the site of cholesterol metabolism) to introduce the same effect permanently.

For now, gene editing of adult bodies is still challenging and is held back by the difficulty of “delivering” the CRISPR instructions to thousands, or even billions of cells—often using viruses to carry the payloads. Organs like the brain and muscles are hard to access, and the treatments can be ordeals. Fatalities in studies aren’t unheard-of. But biotech companies are pouring dollars into new, sleeker ways to deliver CRISPR to hard-to-reach places. Some are designing special viruses that can home in on specific types of cells. Others are adopting nanoparticles similar to those used in the covid-19 vaccines, with the idea of introducing editors easily, and cheaply, via a shot in the arm.

At the Innovative Genomics Institute, a center established by Doudna in Berkeley, California, researchers anticipate that as delivery improves, they will be able to create a kind of CRISPR conveyor belt that, with a few clicks of a mouse, allows doctors to design gene-editing treatments for any serious inherited condition that afflicts children, including immune deficiencies so uncommon that no company will take them on. “This is the trend in my field. We can capitalize on human genetics quite quickly, and the scope of the editable human will rapidly expand,” says Urnov, who works at the institute. “We know that already, today—and forget 2124, this is in 2024—we can build enough CRISPR for the entire planet. I really, really think that [this idea of] gene editing in a syringe will grow. And as it does, we’re going to start to face very clearly the question of how we equitably distribute these resources.”

For now, gene-editing interventions are so complex and costly that only people in wealthy countries are receiving them. The first such therapy to get FDA approval, a treatment for sickle-cell disease, is priced at over $2 million and requires a lengthy hospital stay. Because it’s so difficult to administer, it’s not yet being offered in most of Africa, even though that is where sickle-cell disease is most common. Such disparities are now propelling efforts to greatly simplify gene editing, including a project jointly paid for by the Gates Foundation and the National Institutes of Health that aims to design “shot in the arm” CRISPR, potentially making cures scalable and “accessible to all.” A gene editor built along the lines of the covid-19 vaccine might cost only $1,000. The Gates Foundation sees the technology as a way to widely cure both sickle-cell and HIV—an “unmet need” in Africa, it says. To do that, the foundation is considering introducing into people’s bone marrow the exact HIV-defeating genetic change that He tried to install in embryos.

Then there’s the risk that gene terrorists, or governments, could change people’s DNA without their permission or knowledge.

Scientists can foresee great benefits ahead—even a “final frontier of molecular liberty,” as Christopher Mason, a “space geneticist” at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, characterizes it. Mason works with newer types of gene editors that can turn genes on or off temporarily. He is using these in his lab to make cells resistant to radiation damage. The technology could be helpful to astronauts or, he says, for a weekend of “recreational genomics”—say, boosting your repair genes in preparation to visit the site of the Chernobyl power plant. The technique is “getting to be, I actually think it is, a euphoric application of genetic technologies,” says Mason. “We can say, hey, find a spot on the genome and flip a light switch on or off on any given gene to control its expression at a whim.”

Easy delivery of gene editors to adult bodies could give rise to policy questions just as urgent as the ones raised by the CRISPR babies. Whether we encourage genetic enhancement—in particular, free-market genome upgrades—is one of them. Several online health influencers have already been touting an unsanctioned gene therapy, offered in Honduras, that its creators claim increases muscle mass. Another risk: If changing people’s DNA gets easy enough, gene terrorists or governments could do it without their permission or knowledge. One genetic treatment for a skin disease, approved in the US last year, is formulated as a cream—the first rub-on gene therapy (though not a gene editor).

Some scientists believe new delivery tools should be kept purposefully complex and cumbersome, so that only experts can use them—a biological version of “security through obscurity.” But that’s not likely to happen. “Building a gene editor to make these changes is no longer, you know, the kind of technology that’s in the realm of 100 people who can do it. This is out there,” says Urnov. “And as delivery improves, I don’t know how we will be able to regulate that.”

In our conversation, Urnov frequently returned to that list of superpowers—genetic variants that make some people outliers in one way or another. There is a mutation that allows people to get by on five hours of sleep a night, with no ill effects. There is a woman in Scotland whose genetic peculiarity means she feels no pain and is perpetually happy, though also forgetful. Then there is Eero Mäntyranta, the cross-country ski champion who won three medals at the 1964 Winter Olympics and who turned out to have an inordinate number of red blood cells thanks to an alteration in a gene called the EPO receptor. It’s basically a blueprint for anyone seeking to join the Enhanced Games, the libertarian plan for a pro-doping international sports competition that critics call “borderline criminal” but which has the backing of billionaire Peter Thiel, among others.

All these are possibilities for the future of the human genome, and we won’t even necessarily need to change embryos to get there. Some researchers even expect that with some yet-to-be-conceived technology, updating a person’s DNA could become as simple as sending a document via Wi-Fi, with today’s viruses or nanoparticles becoming anachronisms like floppy disks. I asked Church for his prediction about where gene-editing technology is going in the long term. “Eventually you’d get shot up with a whole bunch of things when you’re born, or it could even be introduced during pregnancy,” he said. “You’d have all the advantages without the disadvantages of being stuck with heritable changes.”

And that will be evolution too.