Why we should thank pigeons for our AI breakthroughs

In 1943, while the world’s brightest physicists split atoms for the Manhattan Project, the American psychologist B.F. Skinner led his own secret government project to win World War II.

Skinner did not aim to build a new class of larger, more destructive weapons. Rather, he wanted to make conventional bombs more precise. The idea struck him as he gazed out the window of his train on the way to an academic conference. “I saw a flock of birds lifting and wheeling in formation as they flew alongside the train,” he wrote. “Suddenly I saw them as ‘devices’ with excellent vision and maneuverability. Could they not guide a missile?”

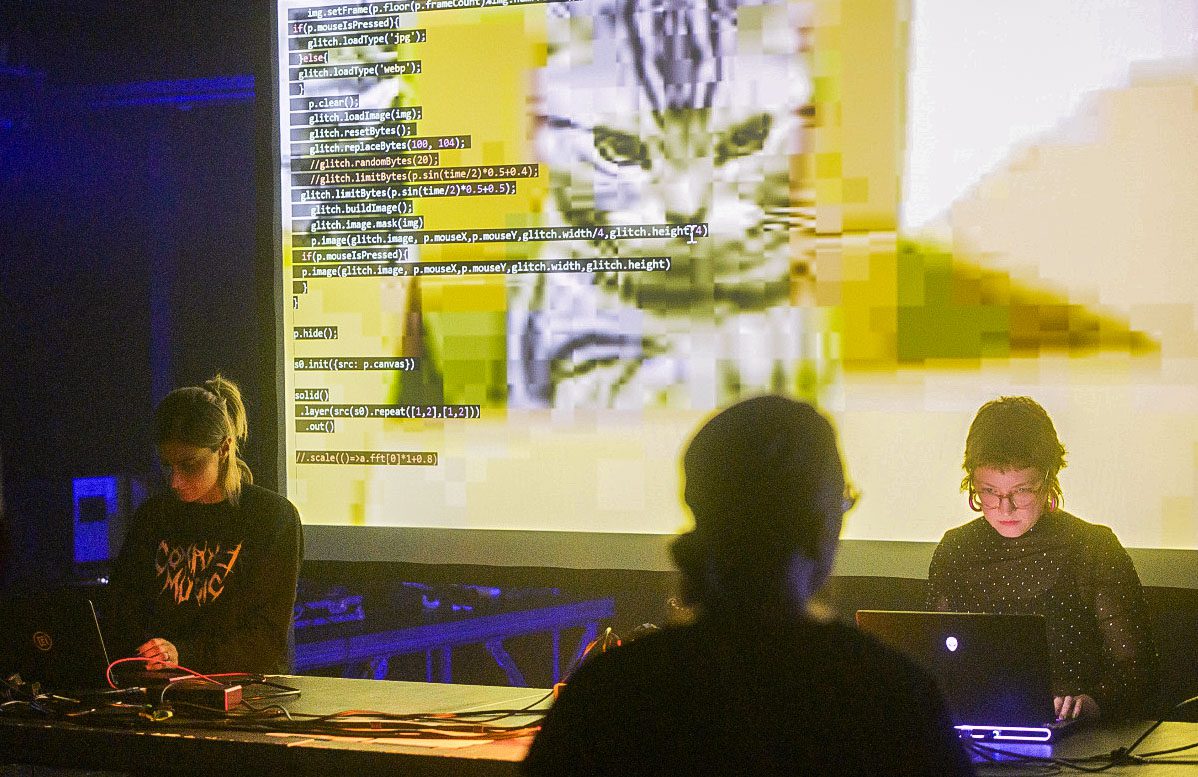

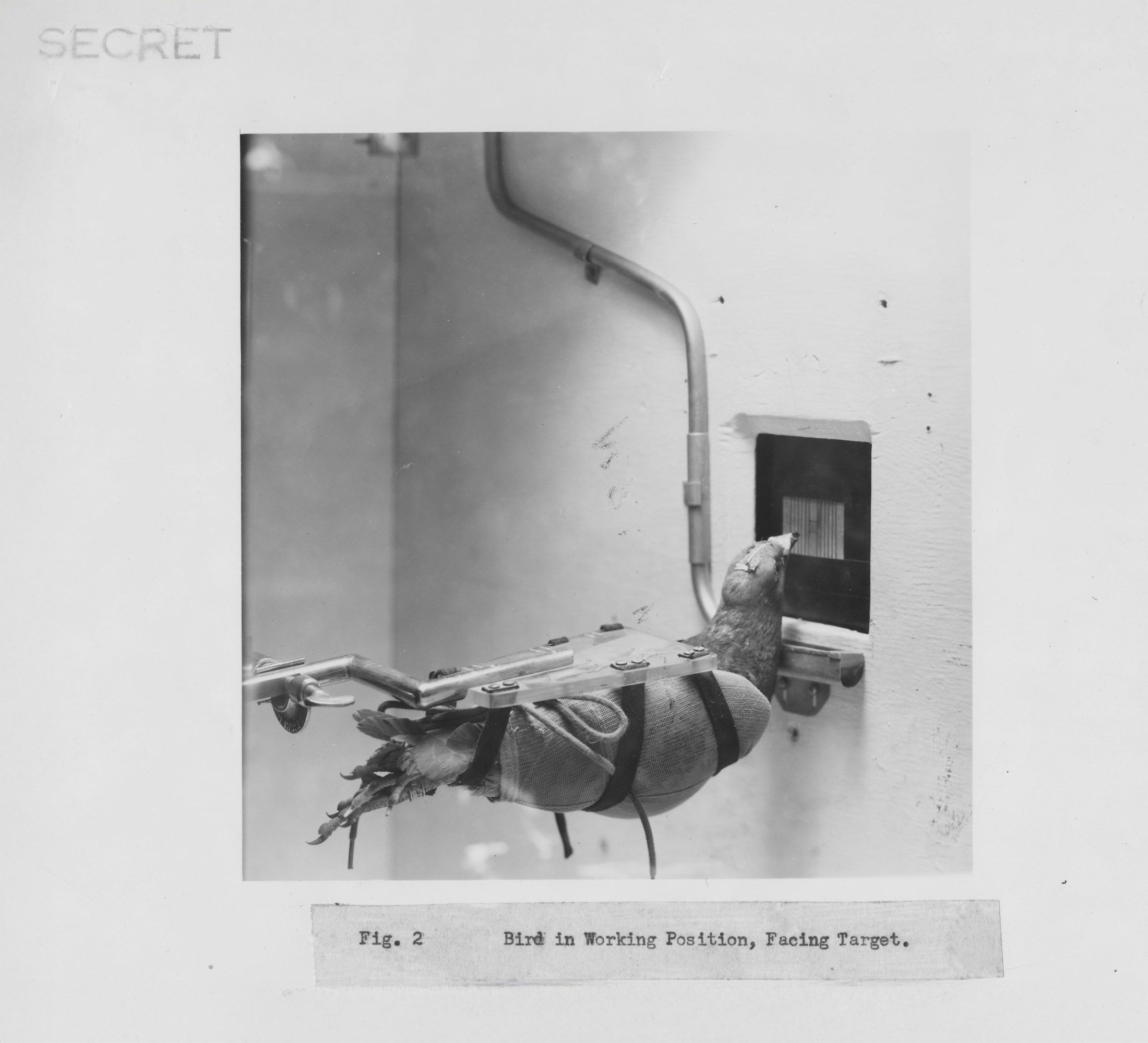

Skinner started his missile research with crows, but the brainy black birds proved intractable. So he went to a local shop that sold pigeons to Chinese restaurants, and “Project Pigeon” was born. Though ordinary pigeons, Columba livia, were no one’s idea of clever animals, they proved remarkably cooperative subjects in the lab. Skinner rewarded the birds with food for pecking at the right target on aerial photographs—and eventually planned to strap the birds into a device in the nose of a warhead, which they would steer by pecking at the target on a live image projected through a lens onto a screen.

The military never deployed Skinner’s kamikaze pigeons, but his experiments convinced him that the pigeon was “an extremely reliable instrument” for studying the underlying processes of learning. “We have used pigeons, not because the pigeon is an intelligent bird, but because it is a practical one and can be made into a machine,” he said in 1944.

People looking for precursors to artificial intelligence often point to science fiction by authors like Isaac Asimov or thought experiments like the Turing test. But an equally important, if surprising and less appreciated, forerunner is Skinner’s research with pigeons in the middle of the 20th century. Skinner believed that association—learning, through trial and error, to link an action with a punishment or reward—was the building block of every behavior, not just in pigeons but in all living organisms, including human beings. His “behaviorist” theories fell out of favor with psychologists and animal researchers in the 1960s but were taken up by computer scientists who eventually provided the foundation for many of the artificial-intelligence tools from leading firms like Google and OpenAI.

These companies’ programs are increasingly incorporating a kind of machine learning whose core concept—reinforcement—is taken directly from Skinner’s school of psychology and whose main architects, the computer scientists Richard Sutton and Andrew Barto, won the 2024 Turing Award, an honor widely considered to be the Nobel Prize of computer science. Reinforcement learning has helped enable computers to drive cars, solve complex math problems, and defeat grandmasters in games like chess and Go—but it has not done so by emulating the complex workings of the human mind. Rather, it has supercharged the simple associative processes of the pigeon brain.

It’s a “bitter lesson” of 70 years of AI research, Sutton has written: that human intelligence has not worked as a model for machine learning—instead, the lowly principles of associative learning are what power the algorithms that can now simulate or outperform humans on a variety of tasks. If artificial intelligence really is close to throwing off the yoke of its creators, as many people fear, then our computer overlords may be less like ourselves than like “rats with wings”—and planet-size brains. And even if it’s not, the pigeon brain can at least help demystify a technology that many worry (or rejoice) is “becoming human.”

In turn, the recent accomplishments of AI are now prompting some animal researchers to rethink the evolution of natural intelligence. Johan Lind, a biologist at Stockholm University, has written about the “associative learning paradox,” wherein the process is largely dismissed by biologists as too simplistic to produce complex behaviors in animals but celebrated for producing humanlike behaviors in computers. The research suggests not only a greater role for associative learning in the lives of intelligent animals like chimpanzees and crows, but also far greater complexity in the lives of animals we’ve long dismissed as simple-minded, like the ordinary Columba livia.

When Sutton began working in AI, he felt as if he had a “secret weapon,” he told me: He had studied psychology as an undergrad. “I was mining the psychological literature for animals,” he says.

Ivan Pavlov began to uncover the mechanics of associative learning at the end of the 19th century in his famous experiments on “classical conditioning,” which showed that dogs would salivate at a neutral stimulus—like a bell or flashing light—if it was paired predictably with the presentation of food. In the middle of the 20th century, Skinner took Pavlov’s principles of conditioning and extended them from an animal’s involuntary reflexes to its overall behavior.

Skinner wrote that “behavior is shaped and maintained by its consequences”—that a random action with desirable results, like pressing a lever that releases a food pellet, will be “reinforced” so that the animal is likely to repeat it. Skinner reinforced his lab animals’ behavior step by step, teaching rats to manipulate marbles and pigeons to play simple tunes on four-key pianos. The animals learned chains of behavior, through trial and error, in order to maximize long-term rewards. Skinner argued that this type of associative learning, which he called “operant conditioning” (and which other psychologists had called “instrumental learning”), was the building block of all behavior. He believed that psychology should study only behaviors that could be observed and measured without ever making reference to an “inner agent” in the mind.

When Richard Sutton began working in AI, he felt as if he had a “secret weapon”: He studied psychology as an undergrad. “I was mining the psychological literature for animals,” he says.

Skinner thought that even human language developed through operant conditioning, with children learning the meanings of words through reinforcement. But his 1957 book on the subject, Verbal Behavior, provoked a brutal review from Noam Chomsky, and psychology’s focus started to swing from observable behavior to innate “cognitive” abilities of the human mind, like logic and symbolic thinking. Biologists soon rebelled against behaviorism also, attacking psychologists’ quest to explain the diversity of animal behavior through an elementary and universal mechanism. They argued that each species evolved specific behaviors suited to its habitat and lifestyle, and that most behaviors were inherited, not learned.

By the ’70s, when Sutton started reading about Skinner’s and similar experiments, many psychologists and researchers interested in intelligence had moved on from pea-brained pigeons, which learn mostly by association, to large-brained animals with more sophisticated behaviors that suggested potential cognitive abilities. “This was clearly old stuff that was not exciting to people anymore,” he told me. Still, Sutton found these old experiments instructive for machine learning: “I was coming to AI with an animal-learning-theorist mindset and seeing the big lack of anything like instrumental learning in engineering.”

Many engineers in the second half of the 20th century tried to model AI on human intelligence, writing convoluted programs that attempted to mimic human thinking and implement rules that govern human response and behavior. This approach—commonly called “symbolic AI”—was severely limited; the programs stumbled over tasks that were easy for people, like recognizing objects and words. It just wasn’t possible to write into code the myriad classification rules human beings use to, say, separate apples from oranges or cats from dogs—and without pattern recognition, breakthroughs in more complex tasks like problem solving, game playing, and language translation seemed unlikely too. These computer scientists, the AI skeptic Hubert Dreyfus wrote in 1972, accomplished nothing more than “a small engineering triumph, an ad hoc solution of a specific problem, without general applicability.”

Pigeon research, however, suggested another route. A 1964 study showed that pigeons could learn to discriminate between photographs with people and photographs without people. Researchers simply presented the birds with a series of images and rewarded them with a food pellet for pecking an image showing a person. They pecked randomly at first but quickly learned to identify the right images, including photos where people were partially obscured. The results suggested that you didn’t need rules to sort objects; it was possible to learn concepts and use categories through associative learning alone.

When Sutton began working with Barto on AI in the late ’70s, they wanted to create a “complete, interactive goal-seeking agent” that could explore and influence its environment like a pigeon or rat. “We always felt the problems we were studying were closer to what animals had to face in evolution to actually survive,” Barto told me. The agent needed two main functions: search, to try out and choose from many actions in a situation, and memory, to associate an action with the situation where it resulted in a reward. Sutton and Barto called their approach “reinforcement learning”; as Sutton said, “It’s basically instrumental learning.” In 1998, they published the definitive exploration of the concept in a book, Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction.

Over the following two decades, as computing power grew exponentially, it became possible to train AI on increasingly complex tasks—that is, essentially, to run the AI “pigeon” through millions more trials.

Programs trained with a mix of human input and reinforcement learning defeated human experts at chess and Atari. Then, in 2017, engineers at Google DeepMind built the AI program AlphaGo Zero entirely through reinforcement learning, giving it a numerical reward of +1 for every game of Go that it won and −1 for every game that it lost. Programmed to seek the maximum reward, it began without any knowledge of Go but improved over 40 days until it attained what its creators called “superhuman performance.” Not only could it defeat the world’s best human players at Go, a game considered even more complicated than chess, but it actually pioneered new strategies that professional players now use.

“Humankind has accumulated Go knowledge from millions of games played over thousands of years,” the program’s builders wrote in Nature in 2017. “In the space of a few days, starting tabula rasa, AlphaGo Zero was able to rediscover much of this Go knowledge, as well as novel strategies that provide new insights into the oldest of games.” The team’s lead researcher was David Silver, who studied reinforcement learning under Sutton at the University of Alberta.

Today, more and more tech companies have turned to reinforcement learning in products such as consumer-facing chatbots and agents. The first generation of generative AI, including large language models like OpenAI’s GPT-2 and GPT-3, tapped into a simpler form of associative learning called “supervised learning,” which trained the model on data sets that had been labeled by people. Programmers often used reinforcement to fine-tune their results by asking people to rate a program’s performance and then giving these ratings back to the program as goals to pursue. (Researchers call this “reinforcement learning from feedback.”)

Then, last fall, OpenAI revealed its o-series of large language models, which it classifies as “reasoning” models. The pioneering AI firm boasted that they are “trained with reinforcement learning to perform reasoning” and claimed they are capable of “a long internal chain of thought.” The Chinese startup DeepSeek also used reinforcement learning to train its attention-grabbing “reasoning” LLM, R1. “Rather than explicitly teaching the model on how to solve a problem, we simply provide it with the right incentives, and it autonomously develops advanced problem-solving strategies,” they explained.

These descriptions might impress users, but at least psychologically speaking, they are confused. A computer trained on reinforcement learning needs only search and memory, not reasoning or any other cognitive mechanism, in order to form associations and maximize rewards. Some computer scientists have criticized the tendency to anthropomorphize these models’ “thinking,” and a team of Apple engineers recently published a paper noting their failure at certain complex tasks and “raising crucial questions about their true reasoning capabilities.”

Sutton, too, dismissed the claims of reasoning as “marketing” in an email, adding that “no serious scholar of mind would use ‘reasoning’ to describe what is going on in LLMs.” Still, he has argued, with Silver and other coauthors, that the pigeons’ method—learning, through trial and error, which actions will yield rewards—is “enough to drive behavior that exhibits most if not all abilities that are studied in natural and artificial intelligence,” including human language “in its full richness.”

In a paper published in April, Sutton and Silver stated that “today’s technology, with appropriately chosen algorithms, already provides a sufficiently powerful foundation to … rapidly progress AI towards truly superhuman agents.” The key, they argue, is building AI agents that depend less than LLMs on human dialogue and prejudgments to inform their behavior.

“Powerful agents should have their own stream of experience that progresses, like humans, over a long time-scale,” they wrote. “Ultimately, experiential data will eclipse the scale and quality of human generated data. This paradigm shift, accompanied by algorithmic advancements in RL, will unlock in many domains new capabilities that surpass those possessed by any human.”

If computers can do all that with just a pigeonlike brain, some animal researchers are now wondering if actual pigeons deserve more credit than they’re commonly given.

“When considered in light of the accomplishments of AI, the extension of associative learning to purportedly more complicated forms of cognitive performance offers fresh prospects for understanding how biological systems may have evolved,” Ed Wasserman, a psychologist at the University of Iowa, wrote in a recent study in the journal Current Biology.

Wasserman trained pigeons to succeed at a complex categorization task, which several undergraduate students failed. The students tried to find a rule that would help them sort various discs; the pigeons simply developed a sense for the group to which any given disc belonged.

In one experiment, Wasserman trained pigeons to succeed at a complex categorization task, which several undergraduate students failed. The students tried, in vain, to find a rule that would help them sort various discs with parallel black lines of various widths and tilts; the pigeons simply developed a sense, through practice and association, for the group to which any given disc belonged.

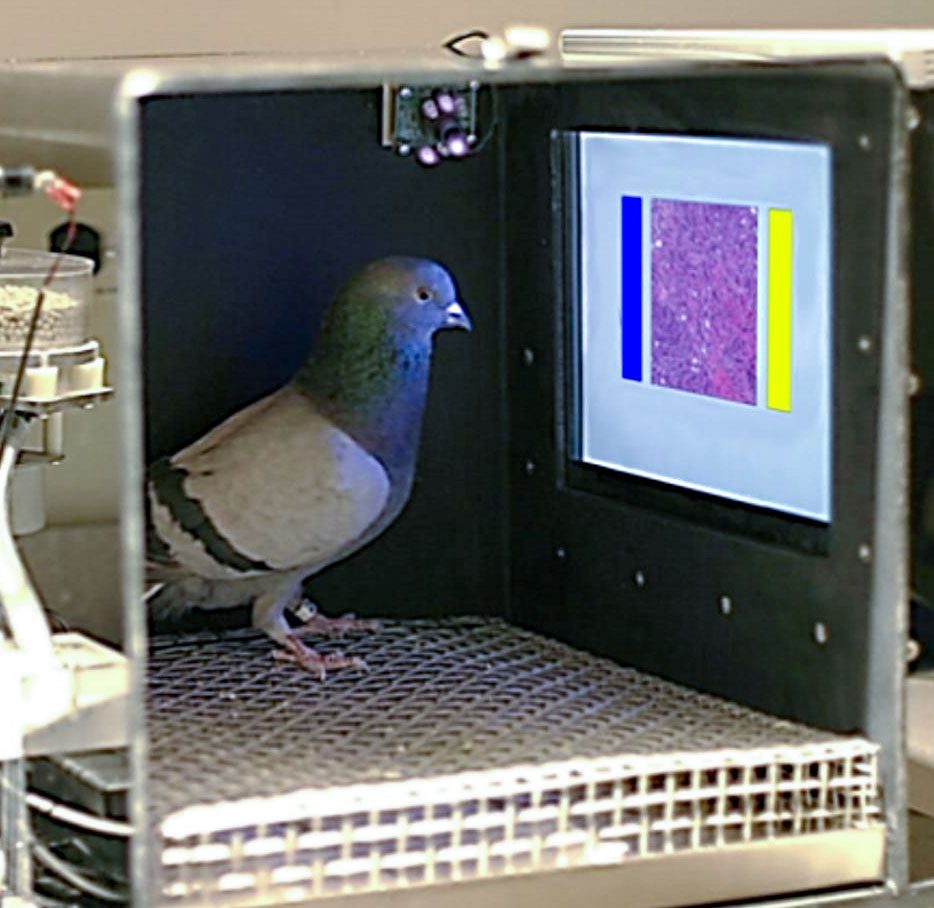

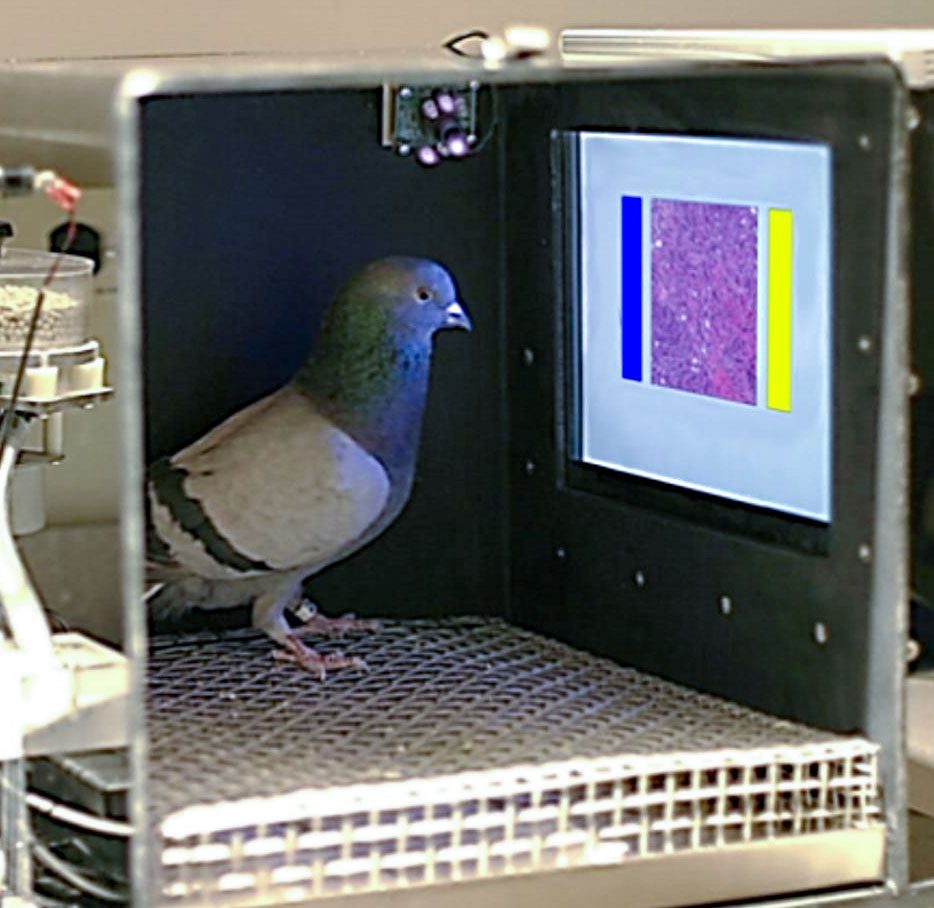

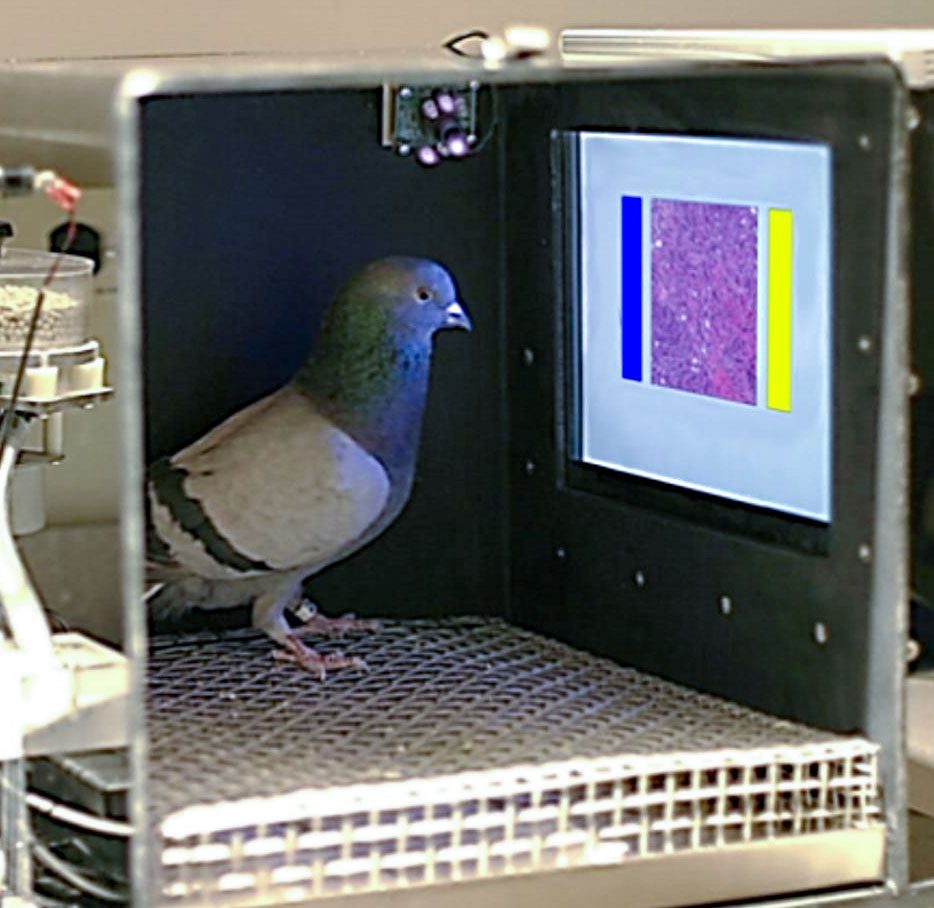

Like Sutton, Wasserman became interested in behaviorist psychology when Skinner’s theories were out of fashion. He didn’t switch to computer science, however: He stuck with pigeons. “The pigeon lives or dies by these really rudimentary learning rules,” Wasserman told me recently, “but they are powerful enough to have succeeded colossally in object recognition.” In his most famous experiments, Wasserman trained pigeons to detect cancerous tissue and symptoms of heart disease in medical scans as accurately as experienced doctors with framed diplomas behind their desks. Given his results, Wasserman found it odd that so many psychologists and ethologists regarded associative learning as a crude, mechanical mechanism, incapable of producing the intelligence of clever animals like apes, elephants, dolphins, parrots, and crows.

Other researchers also started to reconsider the role of associative learning in animal behavior after AI started besting human professionals in complex games. “With the progress of artificial intelligence, which in essence is built upon associative processes, it is increasingly ironic that associative learning is considered too simple and insufficient for generating biological intelligence,” Lind, the biologist from Stockholm University, wrote in 2023. He often cites Sutton and Barto’s computer science in his biological research, and he believes it’s human beings’ symbolic language and cumulative cultures that really put them in a cognitive category of their own.

Ethologists generally propose cognitive mechanisms, like theory of mind (that is, the ability to attribute mental states to others), to explain remarkable animal behaviors like social learning and tool use. But Lind has built models showing that these flexible behaviors could have developed through associative learning, suggesting that there may be no need to invoke cognitive mechanisms at all. If animals learn to associate a behavior with a reward, then the behavior itself will come to approximate the value of the reward. A new behavior can then become associated with the first behavior, allowing the animal to learn chains of actions that ultimately lead to the reward. In Lind’s view, studies demonstrating self-control and planning in chimpanzees and ravens are probably describing behaviors acquired through experience rather than innate mechanisms of the mind.

Lind has been frustrated with what he calls the “low standard that is accepted in animal cognition studies.” As he wrote in an email, “Many researchers in this field do not seem to worry about excluding alternative hypotheses and they seem happy to neglect a lot of current and historical knowledge.” There are some signs, though, that his arguments are catching on. A group of psychologists not affiliated with Lind referenced his “associative learning paradox” last year in a criticism of a Current Biology study, which purported to show that crows used “true statistical inference” and not “low-level associative learning strategies” in an experiment. The psychologists found that they could explain the crows’ performance with a simple reinforcement-learning model—“exactly the kind of low-level associative learning process that [the original authors] ruled out.”

Skinner might have felt vindicated by such arguments. He lamented psychology’s cognitive turn until his death in 1990, maintaining that it was scientifically irresponsible to probe the minds of living beings. After “Project Pigeon,” he became increasingly obsessed with “behaviorist” solutions to societal problems. He went from training pigeons for war to inventions like the “Air Crib,” which aimed to “simplify” baby care by keeping the infant behind glass in a climate-controlled chamber and eliminating the need for clothing and bedding. Skinner rejected free will, arguing that human behavior is determined by environmental variables, and wrote a novel, Walden II, about a utopian community founded on his ideas.

People who care about animals might feel uneasy about a revival in behaviorist theory. The “cognitive revolution” broke with centuries of Western thinking, which had emphasized human supremacy over animals and treated other creatures like stimulus-response machines. But arguing that animals learn by association is not the same as arguing that they are simple-minded. Scientists like Lind and Wasserman do not deny that internal forces like instinct and emotion also influence animal behavior. Sutton, too, believes that animals develop models of the world through their experiences and use them to plan actions. Their point is not that intelligent animals are empty-headed but that associative learning is a much more powerful—indeed, “cognitive”—mechanism than many of their peers believe. The psychologists who recently criticized the study on crows and statistical inference did not conclude that the birds were stupid. Rather, they argued “that a reinforcement learning model can produce complex, flexible behaviour.”

This is largely in line with the work of another psychologist, Robert Rescorla, whose work in the ’70s and ’80s influenced both Wasserman and Sutton. Rescorla encouraged people to think of association not as a “low-level mechanical process” but as “the learning that results from exposure to relations among events in the environment” and “a primary means by which the organism represents the structure of its world.”

This is true even of a laboratory pigeon pecking at screens and buttons in a small experimental box, where scientists carefully control and measure stimuli and rewards. But the pigeon’s learning extends outside the box. Wasserman’s students transport the birds between the aviary and the laboratory in buckets—and experienced pigeons jump immediately into the buckets whenever the students open the doors. Much as Rescorla suggested, they are learning the structure of their world inside the laboratory and the relation of its parts, like the bucket and the box, even though they do not always know the specific task they will face inside.

Comparative psychologists and animal researchers have long grappled with a question that suddenly seems urgent because of AI: How do we attribute sentience to other living beings?

The same associative mechanisms through which the pigeon learns the structure of its world can open a window to the kind of inner life that Skinner and many earlier psychologists said did not exist. Pharmaceutical researchers have long used pigeons in drug-discrimination tasks, where they’re given, say, an amphetamine or a sedative and rewarded with a food pellet for correctly identifying which drug they took. The birds’ success suggests they both experience and discriminate between internal states. “Is that not tantamount to introspection?” Wasserman asked.

It is hard to imagine AI matching a pigeon on this specific task—a reminder that, though AI and animals share associative mechanisms, there is more to life than behavior and learning. A pigeon deserves ethical consideration as a living creature not because of how it learns but because of what it feels. A pigeon can experience pain and suffer, while an AI chatbot cannot—even if some large language models, trained on corpora that include descriptions of human suffering and sci-fi stories of sentient computers, can trick people into believing otherwise.

“The intensive public and private investments into AI research in recent years have resulted in the very technologies that are forcing us to confront the question of AI sentience today,” two philosophers of science wrote in Aeon in 2023. “To answer these current questions, we need a similar degree of investment into research on animal cognition and behavior.” Indeed, comparative psychologists and animal researchers have long grappled with questions that suddenly seem urgent because of AI: How do we attribute sentience to other living beings? How can we distinguish true sentience from a very convincing performance of sentience?

Such an undertaking would yield knowledge not only about technology and animals but also about ourselves. Most psychologists probably wouldn’t go as far as Sutton in arguing that reward is enough to explain most if not all human behavior, but no one would dispute that people often learn by association too. In fact, most of Wasserman’s undergraduate students eventually succeeded at his recent experiment with the striped discs, but only after they gave up searching for rules. They resorted, like the pigeons, to association and couldn’t easily explain afterwards what they’d learned. It was just that with enough practice, they started to get a feel for the categories.

It is another irony about associative learning: What has long been considered the most complex form of intelligence—a cognitive ability like rule-based learning—may make us human, but we also call on it for the easiest of tasks, like sorting objects by color or size. Meanwhile, some of the most refined demonstrations of human learning—like, say, a sommelier learning to taste the difference between grapes—are learned not through rules, but only through experience.

Learning through experience relies on ancient associative mechanisms that we share with pigeons and countless other creatures, from honeybees to fish. The laboratory pigeon is not only in our computers but in our brains—and the engine behind some of humankind’s most impressive feats.

Ben Crair is a science and travel writer based in Berlin.