Yann LeCun’s new venture is a contrarian bet against large language models

Yann LeCun is a Turing Award recipient and a top AI researcher, but he has long been a contrarian figure in the tech world. He believes that the industry’s current obsession with large language models is wrong-headed and will ultimately fail to solve many pressing problems.

Instead, he thinks we should be betting on world models—a different type of AI that accurately reflects the dynamics of the real world. He is also a staunch advocate for open-source AI and criticizes the closed approach of frontier labs like OpenAI and Anthropic.

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that he recently left Meta, where he had served as chief scientist for FAIR (Fundamental AI Research), the company’s influential research lab that he founded. Meta has struggled to gain much traction with its open-source AI model Llama and has seen internal shake-ups, including the controversial acquisition of ScaleAI.

LeCun sat down with MIT Technology Review in an exclusive online interview from his Paris apartment to discuss his new venture, life after Meta, the future of artificial intelligence, and why he thinks the industry is chasing the wrong ideas.

Both the questions and answers below have been edited for clarity and brevity.

You’ve just announced a new company, Advanced Machine Intelligence (AMI). Tell me about the big ideas behind it.

It is going to be a global company, but headquartered in Paris. You pronounce it “ami”—it means “friend” in French. I am excited. There is a very high concentration of talent in Europe, but it is not always given a proper environment to flourish. And there is certainly a huge demand from the industry and governments for a credible frontier AI company that is neither Chinese nor American. I think that is going to be to our advantage.

So an ambitious alternative to the US-China binary we currently have. What made you want to pursue that third path?

Well, there are sovereignty issues for a lot of countries, and they want some control over AI. What I’m advocating is that AI is going to become a platform, and most platforms tend to become open-source. Unfortunately, that’s not really the direction the American industry is taking. Right? As the competition increases, they feel like they have to be secretive. I think that is a strategic mistake.

It’s certainly true for OpenAI, which went from very open to very closed, and Anthropic has always been closed. Google was sort of a little open. And then Meta, we’ll see. My sense is that it’s not going in a positive direction at this moment.

Simultaneously, China has completely embraced this open approach. So all leading open-source AI platforms are Chinese, and the result is that academia and startups, outside of the US, have basically embraced Chinese models. There’s nothing wrong with that—you know, Chinese models are good. Chinese engineers and scientists are great. But you know, if there is a future in which all of our information diet is being mediated by AI assistance, and the choice is either English-speaking models produced by proprietary companies always close to the US or Chinese models which may be open-source but need to be fine-tuned so that they answer questions about Tiananmen Square in 1989—you know, it’s not a very pleasant and engaging future.

They [the future models] should be able to be fine-tuned by anyone and produce a very high diversity of AI assistance, with different linguistic abilities and value systems and political biases and centers of interests. You need high diversity of assistance for the same reason that you need high diversity of press.

That is certainly a compelling pitch. How are investors buying that idea so far?

They really like it. A lot of venture capitalists are very much in favor of this idea of open-source, because they know for a lot of small startups, they really rely on open-source models. They don’t have the means to train their own model, and it’s kind of dangerous for them strategically to embrace a proprietary model.

You recently left Meta. What’s your view on the company and Mark Zuckerberg’s leadership? There’s a perception that Meta has fumbled its AI advantage.

I think FAIR [LeCun’s lab at Meta] was extremely successful in the research part. Where Meta was less successful is in picking up on that research and pushing it into practical technology and products. Mark made some choices that he thought were the best for the company. I may not have agreed with all of them. For example, the robotics group at FAIR was let go, which I think was a strategic mistake. But I’m not the director of FAIR. People make decisions rationally, and there’s no reason to be upset.

So, no bad blood? Could Meta be a future client for AMI?

Meta might be our first client! We’ll see. The work we are doing is not in direct competition. Our focus on world models for the physical world is very different from their focus on generative AI and LLMs.

You were working on AI long before LLMs became a mainstream approach. But since ChatGPT broke out, LLMs have become almost synonymous with AI.

Yes, and we are going to change that. The public face of AI, perhaps, is mostly LLMs and chatbots of various types. But the latest ones of those are not pure LLMs. They are LLM plus a lot of things, like perception systems and code that solves particular problems. So we are going to see LLMs as kind of the orchestrator in systems, a little bit.

Beyond LLMs, there is a lot of AI that is behind the scenes that runs a big chunk of our society. There are assistance driving programs in a car, quick-turn MRI images, algorithms that drive social media—that’s all AI.

You have been vocal in arguing that LLMs can only get us so far. Do you think LLMs are overhyped these days? Can you summarize to our readers why you believe that LLMs are not enough?

There is a sense in which they have not been overhyped, which is that they are extremely useful to a lot of people, particularly if you write text, do research, or write code. LLMs manipulate language really well. But people have had this illusion, or delusion, that it is a matter of time until we can scale them up to having human-level intelligence, and that is simply false.

The truly difficult part is understanding the real world. This is the Moravec Paradox (a phenomenon observed by the computer scientist Hans Moravec in 1988): What’s easy for us, like perception and navigation, is hard for computers, and vice versa. LLMs are limited to the discrete world of text. They can’t truly reason or plan, because they lack a model of the world. They can’t predict the consequences of their actions. This is why we don’t have a domestic robot that is as agile as a house cat, or a truly autonomous car.

We are going to have AI systems that have humanlike and human-level intelligence, but they’re not going to be built on LLMs, and it’s not going to happen next year or two years from now. It’s going to take a while. There are major conceptual breakthroughs that have to happen before we have AI systems that have human-level intelligence. And that is what I’ve been working on. And this company, AMI Labs, is focusing on the next generation.

And your solution is world models and JEPA architecture (JEPA, or “joint embedding predictive architecture,” is a learning framework that trains AI models to understand the world, created by LeCun while he was at Meta). What’s the elevator pitch?

The world is unpredictable. If you try to build a generative model that predicts every detail of the future, it will fail. JEPA is not generative AI. It is a system that learns to represent videos really well. The key is to learn an abstract representation of the world and make predictions in that abstract space, ignoring the details you can’t predict. That’s what JEPA does. It learns the underlying rules of the world from observation, like a baby learning about gravity. This is the foundation for common sense, and it’s the key to building truly intelligent systems that can reason and plan in the real world. The most exciting work so far on this is coming from academia, not the big industrial labs stuck in the LLM world.

The lack of non-text data has been a problem in taking AI systems further in understanding the physical world. JEPA is trained on videos. What other kinds of data will you be using?

Our systems will be trained on video, audio, and sensor data of all kinds—not just text. We are working with various modalities, from the position of a robot arm to lidar data to audio. I’m also involved in a project using JEPA to model complex physical and clinical phenomena.

What are some of the concrete, real-world applications you envision for world models?

The applications are vast. Think about complex industrial processes where you have thousands of sensors, like in a jet engine, a steel mill, or a chemical factory. There is no technique right now to build a complete, holistic model of these systems. A world model could learn this from the sensor data and predict how the system will behave. Or think of smart glasses that can watch what you’re doing, identify your actions, and then predict what you’re going to do next to assist you. This is what will finally make agentic systems reliable. An agentic system that is supposed to take actions in the world cannot work reliably unless it has a world model to predict the consequences of its actions. Without it, the system will inevitably make mistakes. This is the key to unlocking everything from truly useful domestic robots to Level 5 autonomous driving.

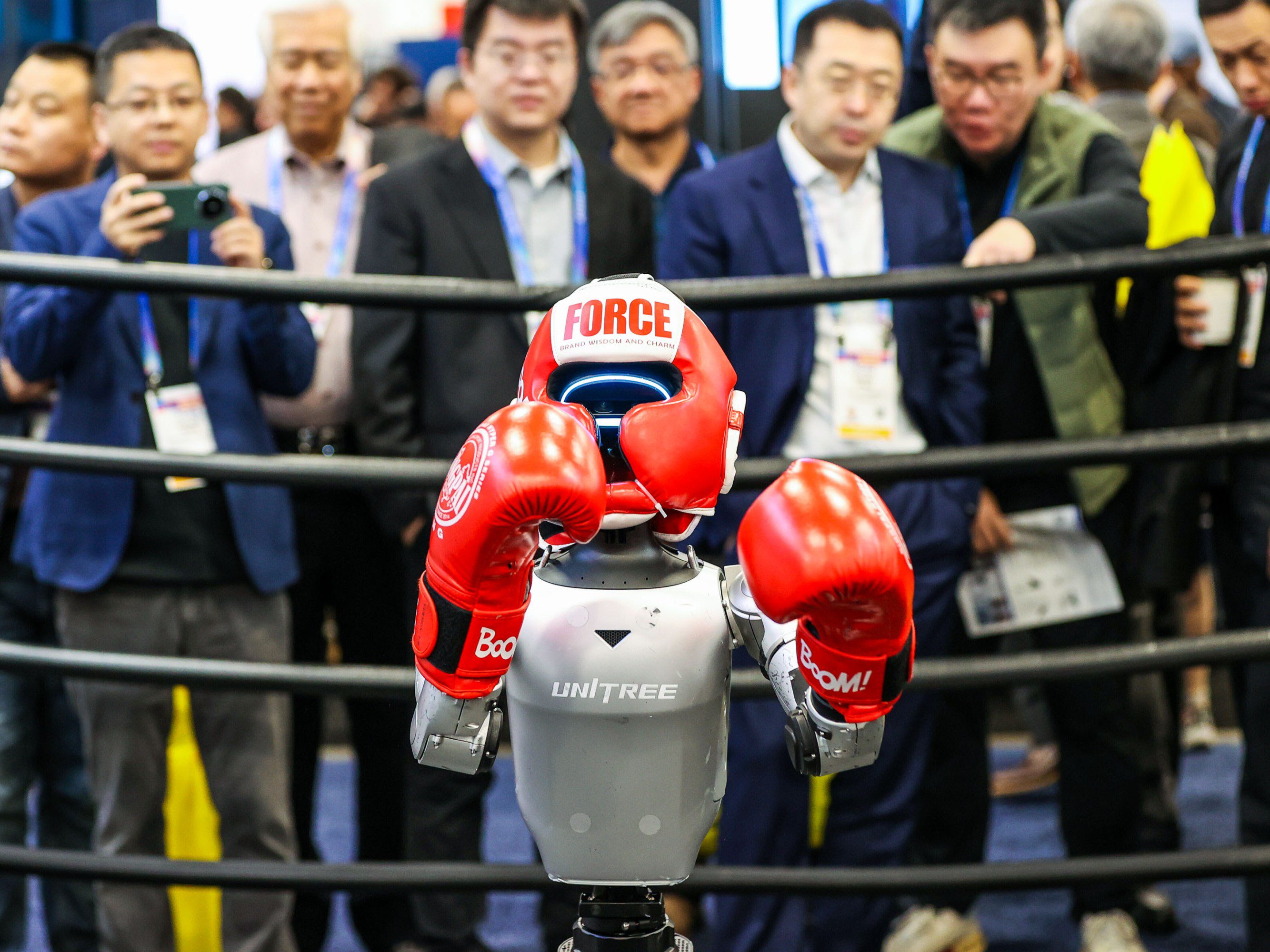

Humanoid robots are all the rage recently, especially ones built by companies from China. What’s your take?

There are all these brute-force ways to get around the limitations of learning systems, which require inordinate amounts of training data to do anything. So the secret of all the companies getting robots to do kung fu or dance is they are all planned in advance. But frankly, nobody—absolutely nobody—knows how to make those robots smart enough to be useful. Take my word for it.

You need an enormous amount of tele-operation training data for every single task, and when the environment changes a little bit, it doesn’t generalize very well. What this tells us is we are missing something very big. The reason why a 17-year-old can learn to drive in 20 hours is because they already know a lot about how the world behaves. If we want a generally useful domestic robot, we need systems to have a kind of good understanding of the physical world. That’s not going to happen until we have good world models and planning.

There’s a growing sentiment that it’s becoming harder to do foundational AI research in academia because of the massive computing resources required. Do you think the most important innovations will now come from industry?

No. LLMs are now technology development, not research. It’s true that it’s very difficult for academics to play an important role there because of the requirements for computation, data access, and engineering support. But it’s a product now. It’s not something academia should even be interested in. It’s like speech recognition in the early 2010s—it was a solved problem, and the progress was in the hands of industry.

What academia should be working on is long-term objectives that go beyond the capabilities of current systems. That’s why I tell people in universities: Don’t work on LLMs. There is no point. You’re not going to be able to rival what’s going on in industry. Work on something else. Invent new techniques. The breakthroughs are not going to come from scaling up LLMs. The most exciting work on world models is coming from academia, not the big industrial labs. The whole idea of using attention circuits in neural nets came out of the University of Montreal. That research paper started the whole revolution. Now that the big companies are closing up, the breakthroughs are going to slow down. Academia needs access to computing resources, but they should be focused on the next big thing, not on refining the last one.

You wear many hats: professor, researcher, educator, public thinker … Now you just took on a new one. What is that going to look like for you?

I am going to be the executive chairman of the company, and Alex LeBrun [a former colleague from Meta AI] will be the CEO. It’s going to be LeCun and LeBrun—it’s nice if you pronounce it the French way.

I am going to keep my position at NYU. I teach one class per year, I have PhD students and postdocs, so I am going to be kept based in New York. But I go to Paris pretty often because of my lab.

Does that mean that you won’t be very hands-on?

Well, there’s two ways to be hands-on. One is to manage people day to day, and another is to actually get your hands dirty in research projects, right?

I can do management, but I don’t like doing it. This is not my mission in life. It’s really to make science and technology progress as far as we can, inspire other people to work on things that are interesting, and then contribute to those things. So that has been my role at Meta for the last seven years. I founded FAIR and led it for four to five years. I kind of hated being a director. I am not good at this career management thing. I’m much more visionary and a scientist.

What makes Alex LeBrun the right fit?

Alex is a serial entrepreneur; he’s built three successful AI companies. The first he sold to Microsoft; the second to Facebook, where he was head of the engineering division of FAIR in Paris. He then left to create Nabla, a very successful company in the health-care space. When I offered him the chance to join me in this effort, he accepted almost immediately. He has the experience to build the company, allowing me to focus on science and technology.

You’re headquartered in Paris. Where else do you plan to have offices?

We are a global company. There’s going to be an office in North America.

New York, hopefully?

New York is great. That’s where I am, right? And it’s not Silicon Valley. Silicon Valley is a bit of a monoculture.

What about Asia? I’m guessing Singapore, too?

Probably, yeah. I’ll let you guess.

And how are you attracting talent?

We don’t have any issue recruiting. There are a lot of people in the AI research community who think the future of AI is in world models. Those people, regardless of pay package, will be motivated to come work for us because they believe in the technological future we are building. We’ve already recruited people from places like OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and xAI.

I heard that Saining Xie, a prominent researcher from NYU and Google DeepMind, might be joining you as chief scientist. Any comments?

Saining is a brilliant researcher. I have a lot of admiration for him. I hired him twice already. I hired him at FAIR, and I convinced my colleagues at NYU that we should hire him there. Let’s just say I have a lot of respect for him.

When will you be ready to share more details about AMI Labs, like financial backing or other core members?

Soon—in February, maybe. I’ll let you know.