Measles is surging in the US. Wastewater tracking could help.

This week marked a rather unpleasant anniversary: It’s a year since Texas reported a case of measles—the start of a significant outbreak that ended up spreading across multiple states. Since the start of January 2025, there have been over 2,500 confirmed cases of measles in the US. Three people have died.

As vaccination rates drop and outbreaks continue, scientists have been experimenting with new ways to quickly identify new cases and prevent the disease from spreading. And they are starting to see some success with wastewater surveillance.

After all, wastewater contains saliva, urine, feces, shed skin, and more. You could consider it a rich biological sample. Wastewater analysis helped scientists understand how covid was spreading during the pandemic. It’s early days, but it is starting to help us get a handle on measles.

Globally, there has been some progress toward eliminating measles, largely thanks to vaccination efforts. Such efforts led to an 88% drop in measles deaths between 2000 and 2024, according to the World Health Organization. It estimates that “nearly 59 million lives have been saved by the measles vaccine” since 2000.

Still, an estimated 95,000 people died from measles in 2024 alone—most of them young children. And cases are surging in Europe, Southeast Asia, and the Eastern Mediterranean region.

Last year, the US saw the highest levels of measles in decades. The country is on track to lose its measles elimination status—a sorry fate that met Canada in November after the country recorded over 5,000 cases in a little over a year.

Public health efforts to contain the spread of measles—which is incredibly contagious—typically involve clinical monitoring in health-care settings, along with vaccination campaigns. But scientists have started looking to wastewater, too.

Along with various bodily fluids, we all shed viruses and bacteria into wastewater, whether that’s through brushing our teeth, showering, or using the toilet. The idea of looking for these pathogens in wastewater to track diseases has been around for a while, but things really kicked into gear during the covid-19 pandemic, when scientists found that the coronavirus responsible for the disease was shed in feces.

This led Marlene Wolfe of Emory University and Alexandria Boehm of Stanford University to establish WastewaterSCAN, an academic-led program developed to analyze wastewater samples across the US. Covid was just the beginning, says Wolfe. “Over the years we have worked to expand what can be monitored,” she says.

Two years ago, for a previous edition of the Checkup, Wolfe told Cassandra Willyard that wastewater surveillance of measles was “absolutely possible,” as the virus is shed in urine. The hope was that this approach could shed light on measles outbreaks in a community, even if members of that community weren’t able to access health care and receive an official diagnosis. And that it could highlight when and where public health officials needed to act to prevent measles from spreading. Evidence that it worked as an effective public health measure was, at the time, scant.

Since then, she and her colleagues have developed a test to identify measles RNA. They trialed it at two wastewater treatment plants in Texas between December 2024 and May 2025. At each site, the team collected samples two or three times a week and tested them for measles RNA.

Over that period, the team found measles RNA in 10.5% of the samples they collected, as reported in a preprint paper published at medRxiv in July and currently under review at a peer-reviewed journal. The first detection came a week before the first case of measles was officially confirmed in the area. That’s promising—it suggests that wastewater surveillance might pick up measles cases early, giving public health officials a head start in efforts to limit any outbreaks.

There are more promising results from a team in Canada. Mike McKay and Ryland Corchis-Scott at the University of Windsor in Ontario and their colleagues have also been testing wastewater samples for measles RNA. Between February and November 2025, the team collected samples from a wastewater treatment facility serving over 30,000 people in Leamington, Ontario.

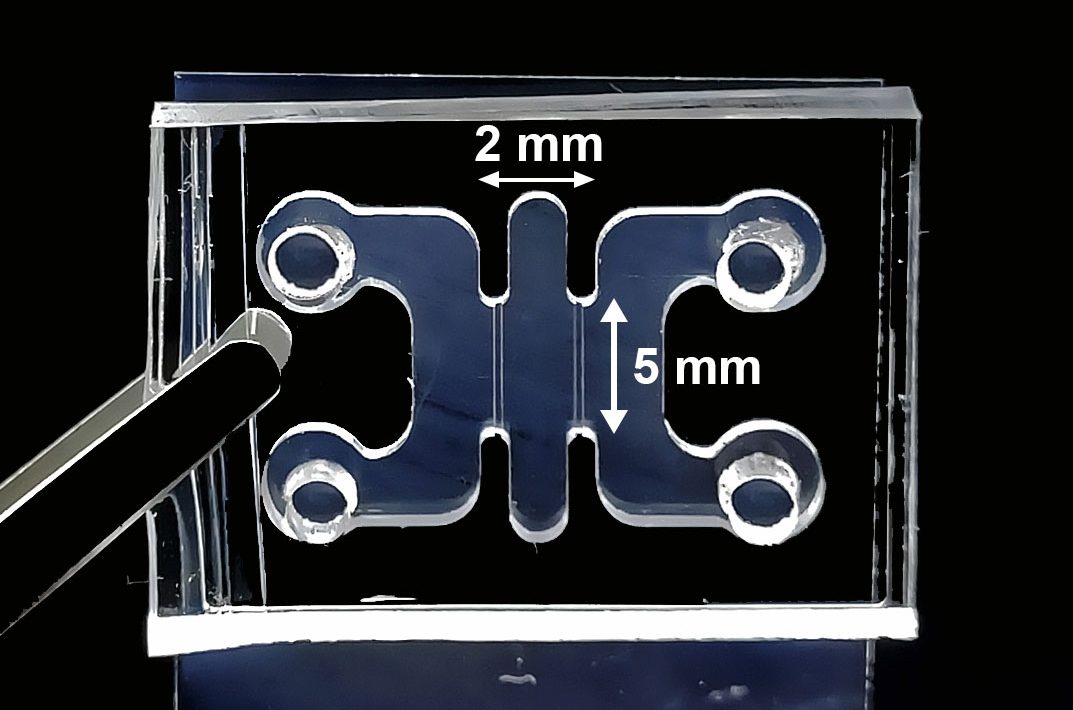

These wastewater tests are somewhat limited—even if they do pick up measles, they won’t tell you who has measles, where exactly infections are occurring, or even how many people are infected. McKay and his colleagues have begun to make some progress here. In addition to monitoring the large wastewater plant, the team used tampons to soak up wastewater from a hospital lateral sewer.

They then compared their measles test results with the number of clinical cases in that hospital. This gave them some idea of the virus’s “shedding rate.” When they applied this to the data collected from the Leamington wastewater treatment facility, the team got estimates of measles cases that were much higher than the figures officially reported.

Their findings track with the opinions of local health officials (who estimate that the true number of cases during the outbreak was around five to 10 times higher than the confirmed case count), the team members wrote in a paper published on medRxiv a couple of weeks ago.

There will always be limits to wastewater surveillance. “We’re looking at the pool of waste of an entire community, so it’s very hard to pull in information about individual infections,” says Corchis-Scott.

Wolfe also acknowledges that “we have a lot to learn about how we can best use the tools so they are useful.” But her team at WastewaterSCAN has been testing wastewater across the US for measles since May last year. And their findings are published online and shared with public health officials.

In some cases, the findings are already helping inform the response to measles. “We’ve seen public health departments act on this data,” says Wolfe. Some have issued alerts, or increased vaccination efforts in those areas, for example. “[We’re at] a point now where we really see public health departments, clinicians, [and] families using that information to help keep themselves and their communities safe,” she says.

McKay says his team has stopped testing for measles because the Ontario outbreak “has been declared over.” He says testing would restart if and when a single new case of measles is confirmed in the region, but he also thinks that his research makes a strong case for maintaining a wastewater surveillance system for measles.

McKay wonders if this approach might help Canada regain its measles elimination status. “It’s sort of like [we’re] a pariah now,” he says. If his approach can help limit measles outbreaks, it could be “a nice tool for public health in Canada to [show] we’ve got our act together.”

This article first appeared in The Checkup, MIT Technology Review’s weekly biotech newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Thursday, and read articles like this first, sign up here.