Michael Skelly hasn’t learned to take no for an answer.

For much of the last 15 years, the Houston-based energy entrepreneur has worked to develop long-haul transmission lines to carry wind power across the Great Plains, Midwest, and Southwest, delivering clean electricity to cities like Albuquerque, Chicago, and Memphis. But so far, he has little to show for the effort.

Skelly has long argued that building such lines and linking together the nation’s grids would accelerate the shift from coal- and natural-gas-fueled power plants to the renewables needed to cut the pollution driving climate change. But his previous business, Clean Line Energy Partners, shut down in 2019, after halting two of its projects and selling off interests in three more.

Skelly contends he was early, not wrong, about the need for such lines, and that the market and policymakers are increasingly coming around to his perspective. Indeed, the US Department of Energy just blessed his latest company’s proposed line with hundreds of millions in grants.

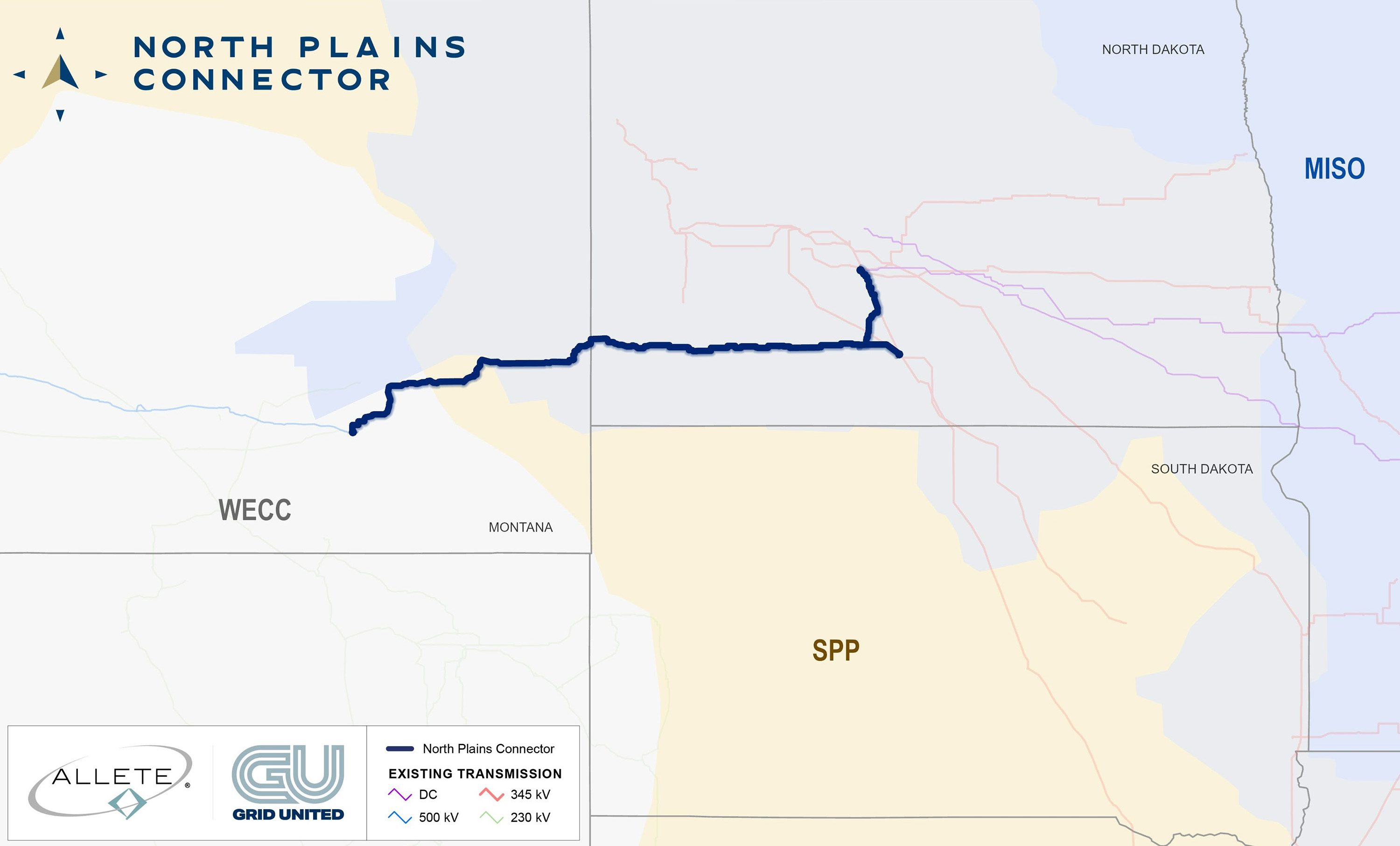

The North Plains Connector would stretch about 420 miles from southeast Montana to the heart of North Dakota and create the first major connection between the US’s two largest grids, enabling system operators to draw on electricity generated by hydro, solar, wind, and other resources across much of the country. This could help keep regional power systems online during extreme weather events and boost the overall share of electricity generated by those clean sources.

Skelly says he’s already secured the support of nine utilities around the region for the project, as well as more than 90% of the landowners along the route.

He says that more and more local energy companies have come to recognize that rising electricity demands, the growing threat storms and fires pose to power systems, and the increasing reliance on renewables have hastened the need for more transmission lines to stitch together and reinforce the country’s fraying, fractured grids.

“There’s a real understanding, really, across the country of the need to invest more in the grid,” says Skelly, now chief executive of Grid United, the Houston-based transmission development firm he founded in 2021. “We need more wires in the air.”

Still, proposals to build long transmission lines frequently stir up controversy in the communities they would cross. It remains to be seen whether this growing understanding will be enough for Skelly’s project to succeed, or to get the US building anywhere near the number of transmission lines it now desperately needs.

Linking grids

Transmission lines are the unappreciated linchpin of the clean-energy transition, arguably as essential as solar panels in cutting emissions and as important as seawalls in keeping people safe.

These long, high, thick wires are often described as the highways of our power systems. They connect the big wind farms, hydroelectric plants, solar facilities, and other power plants to the edges of cities, where substations step down the voltage before delivering electricity into homes and businesses along distribution lines that are more akin to city streets.

There are three major grid systems in the US: the Western Interconnection, the Eastern Interconnection, and the Texas Interconnected System. Regional grid operators such as the California Independent System Operator, the Midcontinent Independent System Operator, and the New York Independent System Operator oversee smaller local grids that are connected, to a greater or lesser extent, within those larger networks.

Transmission lines that could add significant capacity for sharing electricity back and forth across the nation’s major grid systems are especially valuable for cutting emissions and improving the stability of the power system. That’s because they allow those independent system operators to draw on a far larger pool of electricity sources. So if solar power is fading in one part of the country, they could still access wind or hydropower somewhere else. The ability to balance out fluctuations in renewables across regions and seasons, in turn, reduces the need to rely on the steady output of fossil-fuel plants.

“There’s typically excess wind or hydro or other resources somewhere,” says James Hewett, manager of the US policy lobbying group at Breakthrough Energy, the Bill Gates–backed organization focusing on clean energy and climate issues. “But today, the limiting constraint is the ability to move resources from the place where they’re excessive to where they’re needed.”

(Breakthrough Energy Ventures, the investment arm of the firm, doesn’t hold any investments in the North Plains Connector project or Grid United.)

It also means that even if regional wildfires, floods, hurricanes, or heat waves knock out power lines and plants in one area, operators may still be able to tap into adjacent systems to keep the lights on and air-conditioning running. That can be a matter of life and death in the event of such emergencies, as we’ve witnessed in the aftermath of heat waves and hurricanes in recent years.

Studies have shown that weaving together the nation’s grids can boost the share of electricity that renewables reliably provide, significantly cut power-sector emissions, and lower system costs. A recent study by the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab found that the lines interconnecting the US’s major grids and the regions within them offer the greatest economic value among transmission projects, potentially providing more than $100 million in cost savings per year for every additional gigawatt of added capacity. (The study presupposes that the lines are operated efficiently and to their full capacity, among other simplifying assumptions.)

Experts say that grid interconnections can more than pay for themselves over time because, among other improved efficiencies, they allow grid operators to find cheaper sources of electricity at any given time and enable regions to get by with fewer power plants by relying on the redundancy provided by their neighbors.

But as it stands, the meager links between the Eastern Interconnection and Western Interconnection amount to “tiny little soda straws connecting two Olympic swimming pools,” says Rob Gramlich, president of Grid Strategies, a consultancy in Washington, DC.

“A win-win-win”

Grid United’s North Plains Connector, in contrast, would be a fat pipe.

The $3.2 billion, three-gigawatt project would more than double the amount of electricity that could zip back and forth between those grid systems, and it would tightly interlink a trio of grid operators that oversee regional parts of those larger systems: the Western Electricity Coordinating Council, the Midcontinent Independent System Operator, and the Southwest Power Pool. If the line is developed, each could then more easily tap into the richest, cheapest sources at any given time across a huge expanse of the nation, be it hydropower generated in the Northwest, wind turbines cranking across the Midwest, or solar power produced anywhere.

This would ensure that utilities could get greater economic value out of those energy plants, which are expensive to build but relatively cheap to operate, and it would improve the reliability of the system during extreme weather, Skelly says.

“If you’ve got a heat dome in the Northwest, you can send power west,” he says. “If you have a winter storm in the Midwest, you can send power to the east.”

Grid United is developing the project as a joint venture with Allete, an energy company in Duluth, Minnesota, that operates several utilities in the region.

The Department of Energy granted $700 million to a larger regional effort, known as the North Plains Connector Interregional Innovation project, which encompasses two smaller proposals in addition to Grid United’s. The grants will be issued through a more than $10 billion program established under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, enacted by President Joe Biden in 2021.

That funding will likely be distributed to regional utilities and other parties as partial matching grants, designed to incentivize investments in the project among those likely to benefit from it. That design may also help address a chicken-and-egg problem that plagues independent transmission developers like Grid United, Breakthrough’s Hewett says.

Regional utilities can pass along the costs of projects to their electricity customers. Companies like Grid United, however, generally can’t sign up the power producers that will pay to use their lines until they’ve got project approval, but they also often can’t secure traditional financing until they’ve lined up customers.

The DOE funding could ease that issue by providing an assurance of capital that would help get the project through the lengthy permitting process, Hewett says.

“The states are benefiting, local utilities are benefiting, and the developer will benefit,” he says. “It’s a win-win-win.”

Transmission hurdles

Over the years, developers have floated various proposals to more tightly interlink the nation’s major grid systems. But it’s proved notoriously difficult to build any new transmission lines in the US—a problem that has only worsened in recent years.

The nation is developing only 20% of the transmission capacity per year in the 2020s that it did in the early 2010s. On average, interstate transmission lines take eight to 10 years to develop “if they succeed at all,” according to a report from the Niskanen Center.

The biggest challenge in adding connections between grids, says Gramlich of Grid Strategies, is that there’s no clear processes for authorizing lines that cross multiple jurisdictions and no dedicated regional or federal agencies overseeing such proposals. The fact that numerous areas may benefit from such lines also sparks interregional squabbling over how the costs should be allocated.

In addition, communities often balk at the sight of wires and towers, particularly if the benefits of the lines mostly accrue around the end points, not necessarily in all the areas the wires cross. Any city, county, or state, or even one landowner, can hold up a project for years, if not kill it.

But energy companies themselves share much of the blame as well. Regional energy agencies, grid operators, and utilities have actively fought proposals from independent developers to erect wires passing through their territories. They often simply don’t want to forfeit control of their systems, invite added competition, or deal with the regulatory complexity of such projects.

The long delays in building new grid capacity have become a growing impediment to building new energy projects.

As of last year, there were 2,600 gigawatts’ worth of proposed energy generation or storage projects waiting in the wings for transmission capacity that would carry their electricity to customers, according to a recent analysis by Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. That’s roughly the electricity output of 2,600 nuclear reactors, or more than double the nation’s entire power system.

The capacity of projects in the queue has risen almost eightfold from a decade ago, and about 95% of them are solar, wind, or battery proposals.

“Grid interconnection remains a persistent bottleneck,” Joseph Rand, an energy policy researcher at the lab and the lead author of the study, said in a statement.

The legacy of Clean Line Energy

Skelly spent the aughts as the chief development officer of Horizon Wind Energy, a large US wind developer that the Portuguese energy giant EDP snapped up in 2007 for more than $2 billion. Skelly then made a spirited though ill-fated run for Congress in 2008, as the Democratic nominee for the 7th Congressional District of Texas. He ran on a pro-renewables, pro-education campaign but lost by a sizable margin in a district that was solidly Republican.

The following year, he founded Clean Line Energy Partners. The company raised tens of millions of dollars and spent a decade striving to develop five long-range transmission projects that could connect the sorts of wind projects Skelly had worked to build before.

The company did successfully earn some of the permits required for several lines. But it was forced to shut down or offload its projects amid pushback from landowner groups and politicians opposed to renewables, as well as from regional utilities and public utility commissions.

“He was going to play in other people’s sandboxes and they weren’t exactly keen on having him in there,” says Russell Gold, author of Superpower: One Man’s Quest to Transform American Energy, which recounted Skelly’s and Clean Line Energy’s efforts and failures.

Ultimately, those obstacles dragged out the projects beyond the patience of the company’s investors, who declined to continue throwing more money at them, he says.

The company was forced to halt the Centennial West line through New Mexico and the Rock Island project across the Midwest. In addition, it sold off its stake in the Grain Belt Express, which would stretch from Kansas to Indiana, to Invenergy; the Oklahoma portion of the Plains and Eastern line to NextEra Energy; and the Western Spirit line through New Mexico, along with an associated wind farm project, to Pattern Development.

Clean Line Energy itself wound down in 2019.

The Western Spirit transmission line was electrified in late 2021, but the other two projects are still slogging through planning and permitting.

“These things take a long time,” Skelly says.

For all the challenges the company faced, Gold still credits it with raising awareness about the importance and necessity of long-distance interregional transmission. He says it helped spark conversations that led the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to eventually enact rules to support regional transmission planning and encouraged other big players to focus more on building transmission lines.

“I do believe that there is a broader social, political, and commercial awareness now that the United States needs to interconnect its grids,” Gold says.

Lessons learned

Skelly spent a few years as a senior advisor at Lazard, consulting with companies on renewable energy. But he was soon ready to take another shot at developing long-haul transmission lines and started Grid United in 2021.

The new company has proposed four transmission projects in addition to the North Plains Connector—one between Arizona and New Mexico, one between Colorado and Oklahoma, and one each within Texas and Wyoming.

Asked what he thinks the legacy of Clean Line Energy is, Skelly says it’s mixed. But he soon adds that the history of US infrastructure building is replete with projects that didn’t move ahead. The important thing, he says, is to draw the right lessons from those failures.

“When we’re smart about it, we look at the past to see what we can learn,” he says. “We certainly do that today in our business.”

Skelly says one of the biggest takeaways was that it’s important to do the expensive upfront work of meeting with landowners well in advance of applying for permitting, and to use their feedback to guide the line of the route.

Anne Hedges, director of policy and legislative affairs at the Montana Environmental Information Center, confirms that this is the approach Grid United has taken in the region so far.

“A lot of developers seem to be more focused on drawing a straight line on a map rather than working with communities to figure out the best placement for the transmission system,” she says. “Grid United didn’t do that. They got out on the ground and talked to people and planned a route that wasn’t linear.”

The other change that may make Grid United’s project there more likely to move forward has more to do with what the industry’s learned than what Skelly has.

Gramlich says regional grid operators and utilities have become more receptive to collaborating with developers on transmission lines—and for self-interested reasons. They’ll need greater capacity, and soon, to stay online and meet the growing energy demands of data centers, manufacturing facilities, electric vehicles, and buildings, and address the risks to power systems from extreme weather events.

Industry observers are also hopeful that an energy permitting reform bill pending in Congress, along with the added federal funding and new rules requiring transmission providers to do more advance planning, will also help accelerate development. The bipartisan bill promises to shorten the approval process for projects that are determined to be in the national interest. It would also require neighboring areas to work together on interregional transmission planning.

Hundreds of environmental groups have sharply criticized the proposal, which would also streamline approvals for certain oil and gas operations.

“This legislation guts bedrock environmental protections, endangers public health, opens up tens of millions of acres of public lands and hundreds of millions of acres of offshore waters to further oil and gas leasing, gives public lands to mining companies, and would defacto rubberstamp gas export projects that harm frontline communities and perpetuate the climate crisis,” argued a letter signed by 350.org, Earthjustice, the Center for Biological Diversity, the Union of Concerned Scientists, and hundreds of other groups.

But a recent analysis by Third Way, a center-left think tank in Washington, DC, found that the emissions benefits from accelerating transmission permitting could significantly outweigh the added climate pollution from the fossil-fuel provisions in the bill. It projects that the bill would, on balance, reduce global emissions by 400 million to 16.6 billion tons of carbon dioxide through 2050.

“Guardedly optimistic”

Grid United expects to begin applying for county and state permits in the next few months and for federal permits toward the end of the year. It hopes to begin construction within the next four years and switch the line on in 2032.

Since the applications haven’t been made, it’s not clear what individuals or groups are or will be opposed to it—though, given the history of such projects, some will surely object.

Hedges says the Montana Environmental Information Center is reserving judgment until it sees the actual application. She says the organization will be particularly focused on any potential impact on water and wildlife across the region, “making sure that they’re not harming what are already struggling resources in this area.”

So if Skelly was too early with his last company, the obvious question is: Are the market, regulatory, and societal conditions now ripe for interregional transmission lines?

“We’re gonna find out if they are, right?” he says. “We don’t know yet.”

Skelly adds that he doesn’t think the US is going to build as much transmission as it needs to. But he does believe we’ll start to see more projects moving forward—including, he hopes, the North Plains Connector.

“You just can’t count on anything, and you’ve just got to keep going and push, push, push,” he says. “But we’re making good progress. There’s a lot of utility interest. We have a big grant from the DOE, which will help bring down the cost of the project. So knock on wood, we’re guardedly optimistic.”