One day, in the near or far future, an asteroid about the length of a football stadium will find itself on a collision course with Earth. If we are lucky, it will land in the middle of the vast ocean, creating a good-size but innocuous tsunami, or in an uninhabited patch of desert. But if it has a city in its crosshairs, one of the worst natural disasters in modern times will unfold. As the asteroid steams through the atmosphere, it will begin to fragment—but the bulk of it will likely make it to the ground in just a few seconds, instantly turning anything solid into a fluid and excavating a huge impact crater in a heartbeat. A colossal blast wave, akin to one unleashed by a large nuclear weapon, will explode from the impact site in every direction. Homes dozens of miles away will fold like cardboard. Millions of people could die.

Fortunately for all 8 billion of us, planetary defense—the science of preventing asteroid impacts—is a highly active field of research. Astronomers are watching the skies, constantly on the hunt for new near-Earth objects that might pose a threat. And others are actively working on developing ways to prevent a collision should we find an asteroid that seems likely to hit us.

We already know that at least one method works: ramming the rock with an uncrewed spacecraft to push it away from Earth. In September 2022, NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART, showed it could be done when a semiautonomous spacecraft the size of a small car, with solar panel wings, was smashed into an (innocuous) asteroid named Dimorphos at 14,000 miles per hour, successfully changing its orbit around a larger asteroid named Didymos.

But there are circumstances in which giving an asteroid a physical shove might not be enough to protect the planet. If that’s the case, we could need another method, one that is notoriously difficult to test in real life: a nuclear explosion.

Scientists have used computer simulations to explore this potential method of planetary defense. But in an ideal world, researchers would ground their models with cold, hard, practical data. Therein lies a challenge. Sending a nuclear weapon into space would violate international laws and risk inflaming political tensions. What’s more, it could do damage to Earth: A rocket malfunction could send radioactive debris into the atmosphere.

Over the last few years, however, scientists have started to devise some creative ways around this experimental limitation. The effort began in 2023, with a team of scientists led by Nathan Moore, a physicist and chemical engineer at the Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Sandia is a semi-secretive site that serves as the engineering arm of America’s nuclear weapons program. And within that complex lies the Z Pulsed Power Facility, or Z machine, a cylindrical metallic labyrinth of warning signs and wiring. It’s capable of summoning enough energy to melt diamond.

About 25,000 asteroids more than 460 feet long—a size range that starts with midsize “city killers” and goes up in impact from there—are thought to exist close to Earth. Just under half of them have been found.

The researchers reckoned they could use the Z machine to re-create the x-ray blast of a nuclear weapon—the radiation that would be used to knock back an asteroid—on a very small and safe scale.

It took a while to sort out the details. But by July 2023, Moore and his team were ready. They waited anxiously inside a control room, monitoring the thrumming contraption from afar. Inside the machine’s heart were two small pieces of rock, stand-ins for asteroids, and at the press of a button, a maelstrom of x-rays would thunder toward them. If they were knocked back by those x-rays, it would prove something that, until now, was purely theoretical: You can deflect an asteroid from Earth using a nuke.

This experiment “had never been done before,” says Moore. But if it succeeded, its data would contribute to the safety of everyone on the planet. Would it work?

Monoliths and rubble piles

Asteroid impacts are a natural disaster like any other. You shouldn’t lose sleep over the prospect, but if we get unlucky, an errant space rock may rudely ring Earth’s doorbell. “The probability of an asteroid striking Earth during my lifetime is very small. But what if one did? What would we do about it?” says Moore. “I think that’s worth being curious about.”

Forget about the gigantic asteroids you know from Hollywood blockbusters. Space rocks over two-thirds of a mile (about one kilometer) in diameter—those capable of imperiling civilization—are certainly out there, and some hew close to Earth’s own orbit. But because these asteroids are so elephantine, astronomers have found almost all of them already, and none pose an impact threat.

Rather, it’s asteroids a size range down—those upwards of 460 feet (140 meters) long—that are of paramount concern. About 25,000 of those are thought to exist close to our planet, and just under half have been found. The day-to-day odds of an impact are extremely low, but even one of the smaller ones in that size range could do significant damage if it found Earth and hit a populated area—a capacity that has led astronomers to dub such midsize asteroids “city killers.”

If we find a city killer that looks likely to hit Earth, we’ll need a way to stop it. That could be technology to break or “disrupt” the asteroid into fragments that will either miss the planet entirely or harmlessly ignite in the atmosphere. Or it could be something that can deflect the asteroid, pushing it onto a path that will no longer intersect with our blue marble.

Because disruption could accidentally turn a big asteroid into multiple smaller, but still deadly, shards bound for Earth, it’s often considered to be a strategy of last resort. Deflection is seen as safer and more elegant. One way to achieve it is to deploy a spacecraft known as a kinetic impactor—a battering ram that collides with an asteroid and transfers its momentum to the rocky interloper, nudging it away from Earth. NASA’s DART mission demonstrated that this can work, but there are some important caveats: You need to deflect the asteroid years in advance to make sure it completely misses Earth, and asteroids that we spot too late—or that are too big—can’t be swatted away by just one DART-like mission. Instead, you’d need several kinetic impactors—maybe many of them—to hit one side of the asteroid perfectly each time in order to push it far enough to save our planet. That’s a tall order for orbital mechanics, and not something space agencies may be willing to gamble on.

In that case, the best option might instead be to detonate a nuclear weapon next to the asteroid. This would irradiate one hemisphere of the asteroid in x-rays, which in a few millionths of a second would violently shatter and vaporize the rocky surface. The stream of debris spewing out of that surface and into space would act like a rocket, pushing the asteroid in the opposite direction. “There are scenarios where kinetic impact is insufficient, and we’d have to use a nuclear explosive device,” says Moore.

This idea isn’t new. Several decades ago, Peter Schultz, a planetary geologist and impacts expert at Brown University, was giving a planetary defense talk at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, another American lab focused on nuclear deterrence and nuclear physics research. Afterwards, he recalls, none other than Edward Teller, the father of the hydrogen bomb and a key member of the Manhattan Project, invited him into his office for a chat. “He wanted to do one of these near-Earth-asteroid flybys and wanted to test the nukes,” Schultz says. What, he wondered, would happen if you blasted an asteroid with a nuclear weapon’s x-rays? Could you forestall a spaceborne disaster using weapons of mass destruction?

But Teller’s dream wasn’t fulfilled—and it’s unlikely to become a reality anytime soon. The United Nations’ 1967 Outer Space Treaty states that no nation can deploy or use nuclear weapons off-world (even if it’s not clear how long certain spacefaring nations will continue to adhere to that rule).

Even raising the possibility of using nukes to defend the planet can be tricky. “There’re still many folks that don’t want to talk about it at all … even if that were the only option to prevent an impact,” says Megan Bruck Syal, a physicist and planetary defense researcher at Lawrence Livermore. Nuclear weapons have long been a sensitive subject, and with relations between several nuclear nations currently at a new nadir, anxiety over the subject is understandable.

But in the US, there are groups of scientists who “recognize that we have a special responsibility as a spacefaring nation and as a nuclear-capable nation to look at this,” Syal says. “It isn’t our preference to use a nuclear explosive, of course. But we are still looking at it, in case it’s needed.”

But how?

Mostly, researchers have turned to the virtual world, using supercomputers at various US laboratories to simulate the asteroid-agitating physics of a nuclear blast. To put it mildly, “this is very hard,” says Mary Burkey, a physicist and planetary defense researcher at Lawrence Livermore. You cannot simply flick a switch on a computer and get immediate answers. “When a nuke goes off in space, there’s just x-ray light that’s coming out of it. It’s shining on the surface of your asteroid, and you’re tracking those little photons penetrating maybe a tiny little bit into the surface, and then somehow you have to take that micrometer worth of resolution and then propagate it out onto something that might be on the order of hundreds of meters wide, watching that shock wave propagate and then watching fragments spin off into space. That’s four different problems.”

Mimicking the physics of x-ray rock annihilation with as much verisimilitude as possible is difficult work. But recent research using these high-fidelity simulations does suggest that nukes are an effective planetary defense tool for both disruption and deflection. The thing is, though, no two asteroids are alike; each is mechanically and geologically unique, meaning huge uncertainties remain. A more monolithic asteroid might respond in a straightforward way to a nuclear deflection campaign, whereas a rubble pile asteroid—a weakly bound fleet of boulders barely held together by their own gravity—might respond in a chaotic, uncontrollable way. Can you be sure the explosion wouldn’t accidentally shatter the asteroid, turning a cannonball into a hail of bullets still headed for Earth?

Simulations can go a long way toward answering these questions, but they remain virtual re-creations of reality, with built-in assumptions. “Our models are only as good as the physics that we understand and that we put into them,” says Angela Stickle, a hypervelocity impact physicist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland. To make sure the simulations are reproducing the correct physics and delivering realistic data, physical experiments are needed to ground them.

Every firing of the Z machine carries the energy of more than 1,000 lightning bolts, and each shot lasts a few millionths of a second.

Researchers studying kinetic impactors can get that sort of real-world data. Along with DART, they can use specialized cannons—like the Vertical Gun Range at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California—to fire all sorts of projectiles at meteorites. In doing so, they can find out how tough or fragile asteroid shards can be, effectively reproducing a kinetic impact mission on a small scale.

Battle-testing nuke-based asteroid defense simulations is another matter. Re-creating the physics of these confrontations on a small scale was long considered to be exceedingly difficult. Fortunately, those keen on fighting asteroids are as persistent as they are creative—and several teams, including Moore’s at Sandia, think they have come up with a solution.

X-ray scissors

The prime mission of Sandia, like that of Lawrence Livermore, is to help maintain the nation’s nuclear weapons arsenal. “It’s a national security laboratory,” says Moore. “Planetary defense affects the entire planet,” he adds—making it, by default, a national security issue as well. And that logic, in part, persuaded the powers that be in July 2022 to try a brand-new kind of experiment. Moore took charge of the project in January 2023—and with the shot scheduled for the summer, he had only a few months to come up with the specific plan for the experiment. There was “lots of scribbling on my whiteboard, running computer simulations, and getting data to our engineers to design the test fixture for the several months it would take to get all the parts machined and assembled,” he says.

Although there were previous and ongoing experiments that showered asteroid-like targets with x-rays, Moore and his team were frustrated by one aspect of them. Unlike actual asteroids floating freely in space, the micro-asteroids on Earth were fixed in place. To truly test whether x-rays could deflect asteroids, targets would have to be suspended in a vacuum—and it wasn’t immediately clear how that could be achieved.

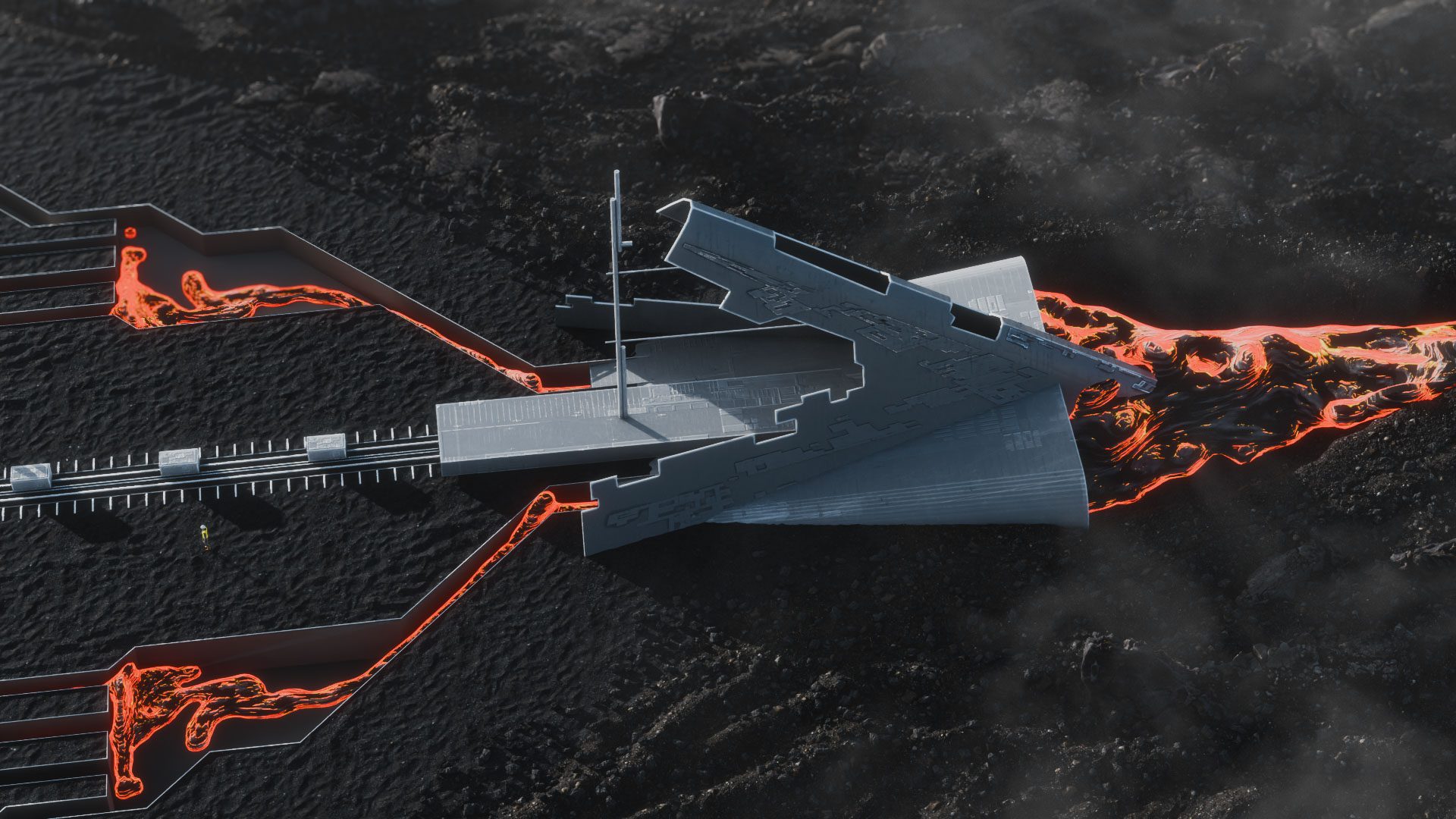

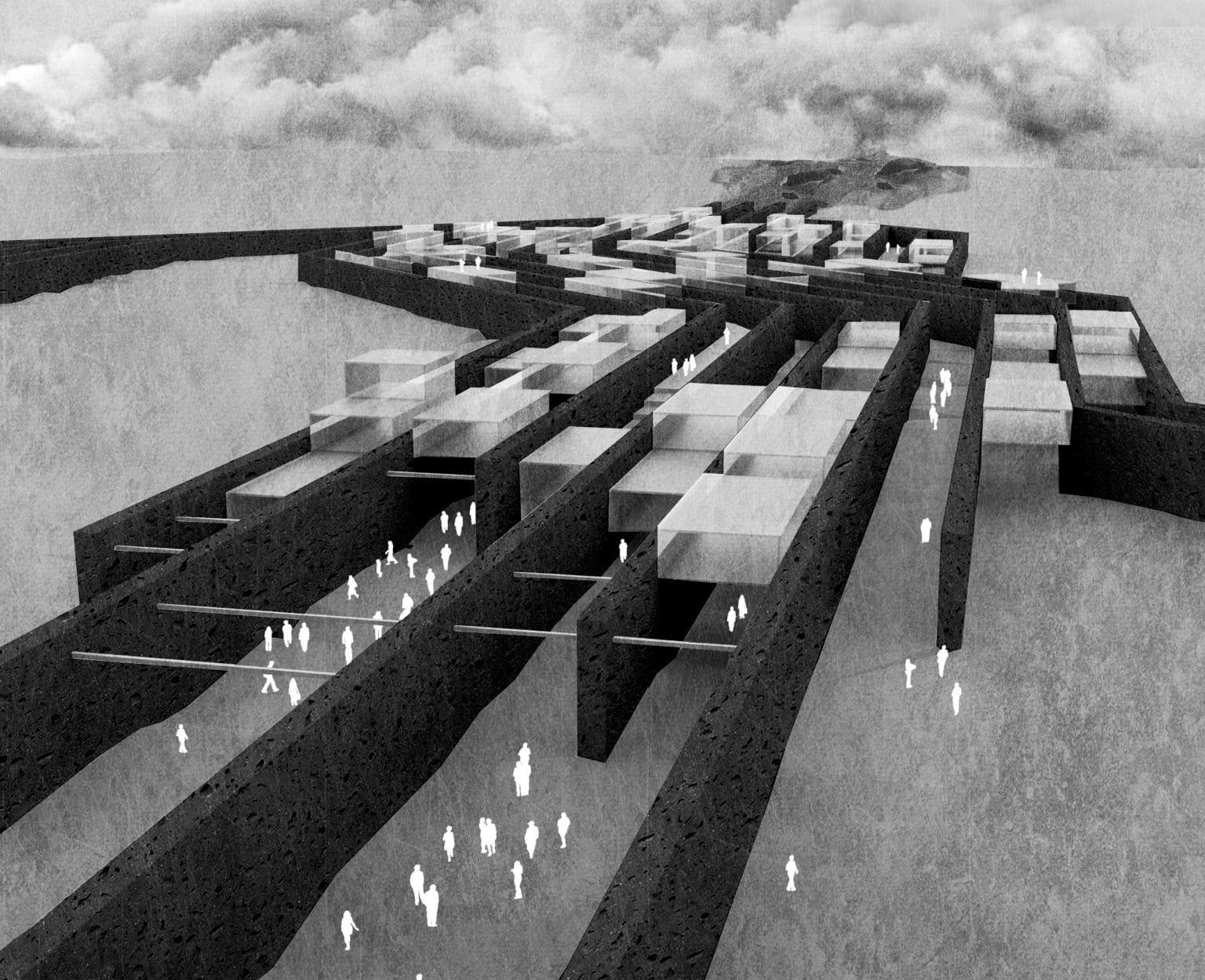

Generating the nuke-like x-rays was the easy part, because Sandia had the Z machine, a hulking mass of diodes, pipes, and wires interwoven with an assortment of walkways that circumnavigate a vacuum chamber at its core. When it’s powered up, electrical currents are channeled into capacitors—and, when commanded, blast that energy at a target or substance to create radiation and intense magnetic pressures.

Flanked by klaxons and flashing lights, it’s an intimidating sight. “It’s the size of a building—about three stories tall,” says Moore. Every firing of the Z machine carries the energy of more than 1,000 lightning bolts, and each shot lasts a few millionths of a second: “You can’t even blink that fast.” The Z machine is named for the axis along which its energetic particles cascade, but the Z could easily stand for “Zeus.”

The original purpose of the Z machine, whose first form was built half a century ago, was nuclear fusion research. But over time, it’s been tinkered with, upgraded, and used for all kinds of science. “The Z machine has been used to compress matter to the same densities [you’d find at] the centers of planets. And we can do experiments like that to better understand how planets form,” Moore says, as an example. And the machine’s preternatural energies could easily be used to generate x-rays—in this case, by electrifying and collapsing a cloud of argon gas.

“The idea of studying asteroid deflection is completely different for us,” says Moore. And the machine “fires just once a day,” he adds, “so all the experiments are planned more than a year in advance.” In other words, the researchers had to be near certain their one experiment would work, or they would be in for a long wait to try again—if they were permitted a second attempt.

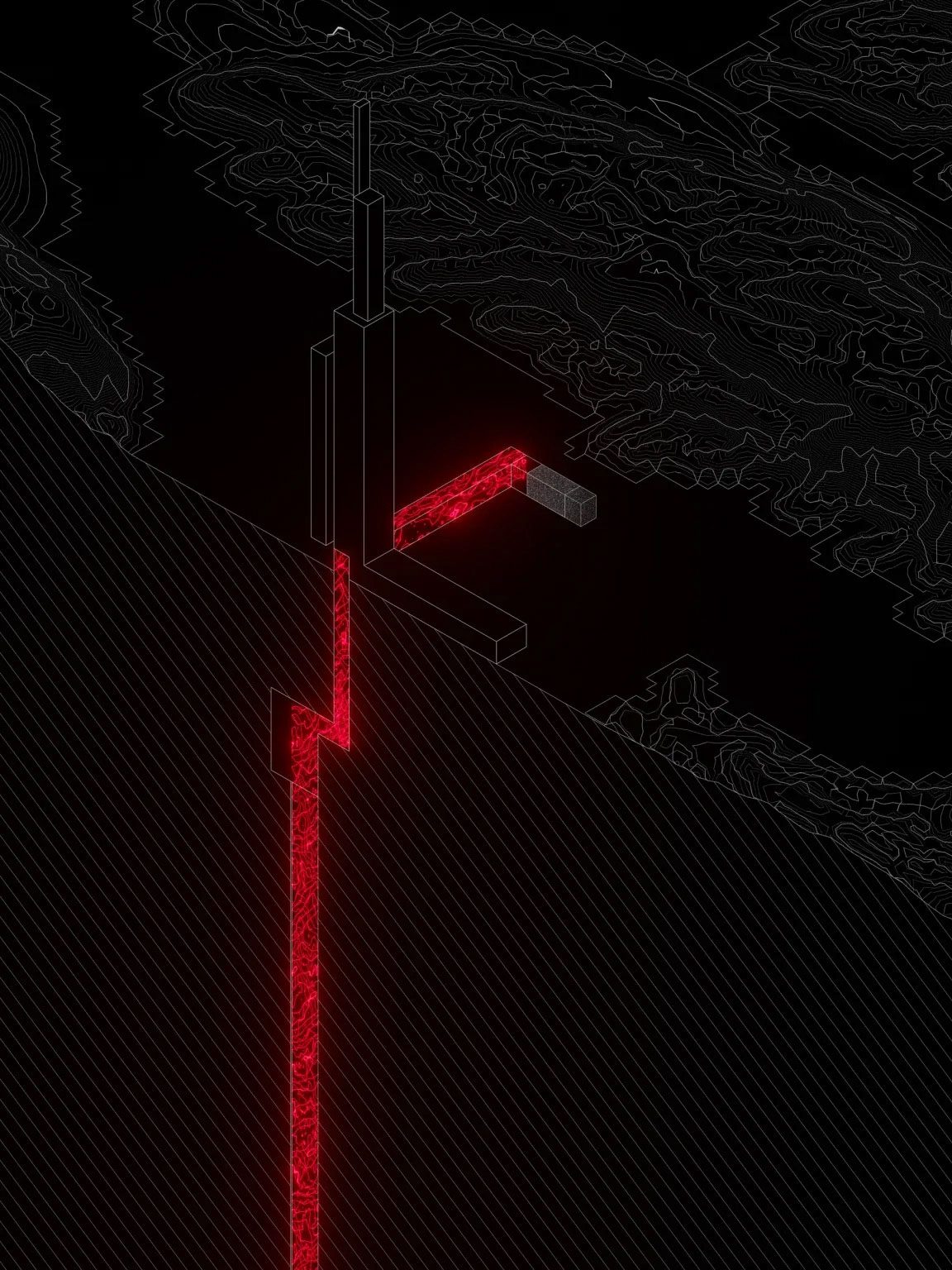

For some time, they could not figure out how to suspend their micro-asteroids. But eventually, they found a solution: Two incredibly thin bits of aluminum foil would hold their targets in place within the Z machine’s vacuum chamber. When the x-ray blast hit them and the targets, the pieces of foil would be instantly vaporized, briefly leaving the targets suspended in the chamber and allowing them to be pushed back as if they were in space. “It’s like you wave your magic wand and it’s gone,” Moore says of the foil. He dubbed this technique “x-ray scissors.”

In July 2023, after considerable planning, the team was ready. Within the Z machine’s vacuum chamber were two fingernail-size targets—a bit of quartz and some fused silica, both frequently found on real asteroids. Nearby, a pocket of argon gas swirled away. Satisfied that the gigantic gizmo was ready, everyone left and went to stand in the control room. For a moment, it was deathly quiet.

Stand by.

Fire.

It was over before their ears could even register a metallic bang. A tempest of electricity shocked the argon gas cloud, causing it to implode; as it did, it transformed into a plasma and x-rays screamed out of it, racing toward the two targets in the chamber. The foil vanished, the surfaces of both targets erupted outward as supersonic sprays of debris, and the targets flew backward, away from the x-rays, at 160 miles per hour.

Moore wasn’t there. “I was in Spain when the experiment was run, because I was celebrating my anniversary with my wife, and there was no way I was going to miss that,” he says. But just after the Z machine was fired, one of his colleagues sent him a very concise text: IT WORKED.

“We knew right away it was a huge success,” says Moore. The implications were immediately clear. The experimental setup was complex, but they were trying to achieve something extremely fundamental: a real-world demonstration that a nuclear blast could make an object in space move.

“We’re genuinely looking at this from the standpoint of ‘This is a technology that could save lives.’”

Patrick King, a physicist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, was impressed. Previously, pushing back objects using x-ray vaporization had been extremely difficult to demonstrate in the lab. “They were able to get a direct measurement of that momentum transfer,” he says, calling the x-ray scissors an “elegant” technique.

Sandia’s work took many in the community by surprise. “The Z machine experiment was a bit of a newcomer for the planetary defense field,” says Burkey. But she notes that we can’t overinterpret the results. It isn’t clear, from the deflection of the very small and rudimentary asteroid-like targets, how much a genuine nuclear explosion would deflect an actual asteroid. As ever, more work is needed.

King leads a team that is also working on this question. His NASA-funded project involves the Omega Laser Facility, a complex based at the University of Rochester in upstate New York. Omega can generate x-rays by firing powerful lasers at a target within a specialized chamber. Upon being irradiated, the target generates an x-ray flash, similar to the one produced during a nuclear explosion in space, which can then be used to bombard various objects—in this case, some Earth rocks acting as asteroid mimics, and (crucially) some bona fide meteoritic material too.

King’s Omega experiments have tried to answer a basic question: “How much material actually gets removed from the surface?” says King. The amount of material that flies off the pseudo-asteroids, and the vigor with which it’s removed, will differ from target to target. The hope is that these results—which the team is still considering—will hint at how different types of asteroids will react to being nuked. Although experiments with Omega cannot produce the kickback seen in the Z machine, King’s team has used a more realistic and diverse series of targets and blasted them with x-rays hundreds of times. That, in turn, should clue us in to how effectively, or not, actual asteroids would be deflected by a nuclear explosion.

“I wouldn’t say one [experiment] has definitive advantages over the other,” says King. “Like many things in science, each approach can yield insight along different ‘axes,’ if you will, and no experimental setup gives you the whole picture.”

Experiments like Moore’s and King’s may sound technologically baroque—a bit like lightning-fast Rube Goldberg machines overseen by wizards. But they are likely the first in a long line of increasingly sophisticated tests. “We’ve just scratched the surface of what we can do,” Moore says. As with King’s experiments, Moore hopes to place a variety of materials in the Z machine, including targets that can stand in for the wetter, more fragile carbon-rich asteroids that astronomers commonly see in near-Earth space. “If we could get our hands on real asteroid material, we’d do it,” he says. And it’s expected that all this experimental data will be fed back into those nuke-versus-asteroid computer simulations, helping to verify the virtual results.

Although these experiments are perfectly safe, planetary defenders remain fully cognizant of the taboo around merely discussing the use of nukes for any reason—even if that reason is potentially saving the world. “We’re genuinely looking at this from the standpoint of ‘This is a technology that could save lives,’” King says.

Inevitably, Earth will be imperiled by a dangerous asteroid. And the hope is that when that day arrives, it can be dealt with using something other than a nuke. But comfort should be taken from the fact that scientists are researching this scenario, just in case it’s our only protection against the firmament. “We are your taxpayer dollars at work,” says Burkey.

There’s still some way to go before they can be near certain that this asteroid-stopping technique will succeed. Their progress, though, belongs to everyone. “Ultimately,” says Moore, “we all win if we solve this problem.”

Robin George Andrews is an award-winning science journalist based in London and the author, most recently, of How to Kill an Asteroid: The Real Science of Planetary Defense.