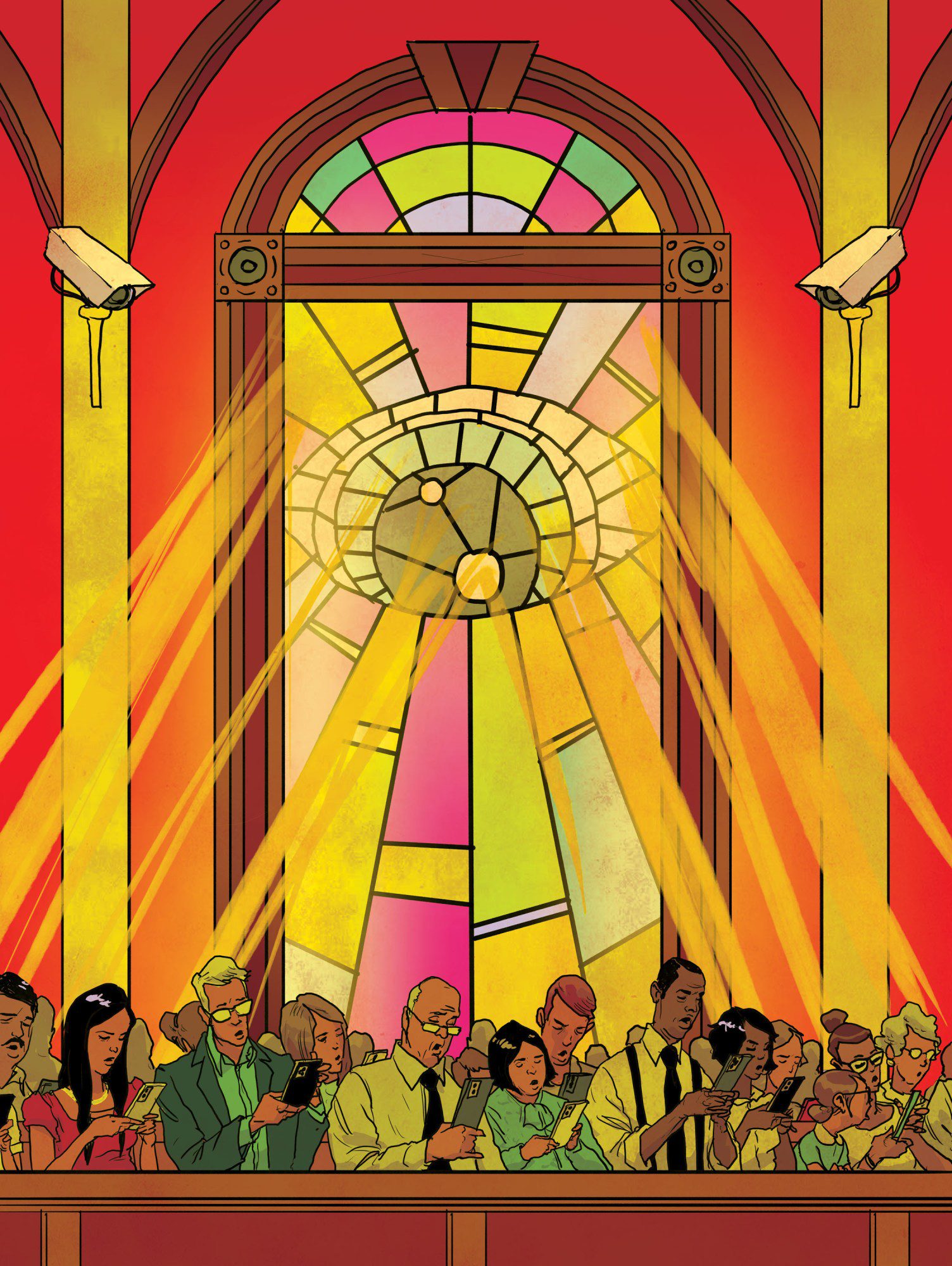

On a Sunday morning in a Midwestern megachurch, worshippers step through sliding glass doors into a bustling lobby—unaware they’ve just passed through a gauntlet of biometric surveillance. High-speed cameras snap multiple face “probes” per second, isolating eyes, noses, and mouths before passing the results to a local neural network that distills these images into digital fingerprints. Before people find their seats, they are matched against an on-premises database—tagged with names, membership tiers, and watch-list flags—that’s stored behind the church’s firewall.

Late one afternoon, a woman scrolls on her phone as she walks home from work. Unbeknownst to her, a complex algorithm has stitched together her social profiles, her private health records, and local veteran outreach lists. It flags her for past military service, chronic pain, opioid dependence, and high Christian belief, and then delivers an ad to her Facebook feed: “Struggling with pain? You’re not alone. Join us this Sunday.”

These hypothetical scenes reflect real capabilities increasingly woven into places of worship nationwide, where spiritual care and surveillance converge in ways few congregants ever realize. Where Big Tech’s rationalist ethos and evangelical spirituality once mixed like oil and holy water, this unlikely amalgam has given birth to an infrastructure already reshaping the theology of trust—and redrawing the contours of community and pastoral power in modern spiritual life.

An ecumenical tech ecosystem

The emerging nerve center of this faith-tech nexus is in Boulder, Colorado, where the spiritual data and analytics firm Gloo has its headquarters.

Gloo captures congregants across thousands of data points that make up a far richer portrait than any snapshot. From there, the company is constructing a digital infrastructure meant to bring churches into the age of algorithmic insight.

The church is “a highly fragmented market that is one of the largest yet to fully adopt digital technology,” the company said in a statement by email. “While churches have a variety of goals to achieve their mission, they use Gloo to help them connect, engage with, and know their people on a deeper level.”

Gloo was founded in 2013 by Scott and Theresa Beck. From the late 1980s through the 2000s, Scott was turning Blockbuster into a 3,500-store chain, taking Boston Market public, and founding Einstein Bros. Bagels before going on to seed and guide startups like Ancestry.com and HomeAdvisor. Theresa, an artist, has built a reputation creating collaborative, eco-minded workshops across Colorado and beyond. Together, they have recast pastoral care as a problem of predictive analytics and sold thousands of churches on the idea that spiritual health can be managed like customer engagement.

Think of Gloo as something like Salesforce but for churches: a behavioral analytics platform, powered by church-generated insights, psychographic information, and third-party consumer data. The company prefers to refer to itself as “a technology platform for the faith ecosystem.” Either way, this information is integrated into its “State of Your Church” dashboard—an interface for the modern pulpit. The result is a kind of digital clairvoyance: a crystal ball for knowing whom to check on, whom to comfort, and when to act.

Thousands of churches have been sold on the idea that spiritual health can be managed like customer engagement.

Gloo ingests every one of the digital breadcrumbs a congregant leaves—how often you attend church, how much money you donate, which church groups you sign up for, which keywords you use in your online prayer requests—and then layers on third-party data (census demographics, consumer habits, even indicators for credit and health risks). Behind the scenes, it scores and segments people and groups—flagging who is most at risk of drifting, primed for donation appeals, or in need of pastoral care. On that basis, it auto-triggers tailored outreach via text, email, or in-app chat. All the results stream into the single dashboard, which lets pastors spot trends, test messaging, and forecast giving and attendance. Essentially, the system treats spiritual engagement like a marketing funnel.

Since its launch in 2013, Gloo has steadily increased its footprint, and it has started to become the connective tissue for the country’s fragmented religious landscape. According to the Hartford Institute for Religion Research, the US is home to around 370,000 distinct congregations. As of early 2025, according to figures provided by the company, Gloo held contracts with more than 100,000 churches and ministry leaders.

In 2024, the company secured a $110 million strategic investment, backed by “mission-aligned” investors ranging from a child-development NGO to a denominational finance group. That cemented its evolution from basic church services vendor to faith-tech juggernaut.

It started snapping up and investing in a constellation of ministry tools—everything from automated sermon distribution to real-time giving and attendance analytics, AI-driven chatbots, and leadership content libraries. By layering these capabilities onto its core platform, the company has created a one-stop shop for churches that combines back-office services with member-engagement apps and psychographic insights to fully realize that unified “faith ecosystem.”

And just this year, two major developments brought this strategy into sharper focus.

In March 2025, Gloo announced that former Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger—who has served as its chairman of the board since 2018—would assume an expanded role as executive chair and head of technology. Gelsinger, whom the company describes as “a great long-term investor and partner,” is a technologist whose fingerprints are on Intel’s and VMware’s biggest innovations.

(It is worth noting that Intel shareholders have filed a lawsuit against Gelsinger and CFO David Zinsner seeking to claw back roughly $207 million in compensation to Gelsinger, alleging that between 2021 and 2023, he repeatedly misled investors about the health of Intel Foundry Services.)

The same week Gloo announced Gelsinger’s new role, it unveiled a strategic investment in Barna Group, the Texas-based research firm whose four decades of surveying more than 2 million self-identified Christians underpin its annual reports on worship, beliefs, and cultural engagement. Barna’s proprietary database—covering every region, age cohort, and denomination—has made it the go-to insight engine for pastors, seminaries, and media tracking the pulse of American faith.

“We’ve been acquiring about a company a month into the Gloo family, and we expect that to continue,” Gelsinger told MIT Technology Review in June. “I’ve got three meetings this week on different deals we’re looking at.” (A Gloo spokesperson declined to confirm the pace of acquisitions, stating only that as of April 30, 2025, the company had fully acquired or taken majority ownership in 15 “mission-aligned companies.”)

“The idea is, the more of those we can bring in, the better we can apply the platform,” Gelsinger said. “We’re already working with companies with decades of experience, but without the scale, the technology, or the distribution we can now provide.”

In particular, Barna’s troves of behavioral, spiritual, and cultural data offer granular insight into the behaviors, beliefs, and anxieties of faith communities. While the two organizations frame the collaboration in terms of serving church leaders, the mechanics resemble a data-fusion engine of impressive scale: Barna supplies the psychological texture, and Gloo provides the digital infrastructure to segment, score, and deploy the information.

In a promotional video from 2020 that is no longer available online, Gloo claimed to provide “the world’s first big-data platform centered around personal growth,” promising pastors a 360-degree view of congregants, including flags for substance use or mental-health struggles. Or, as the video put it, “Maximize your capacity to change lives by leveraging insights from big data, understand the people you want to serve, reach them earlier, and turn their needs into a journey toward growth.”

Gloo is also now focused on supercharging its services with artificial intelligence and using these insights to transcend market research. The company aims to craft AI models that aren’t just trained on theology but anticipate the moments when people’s faith—and faith leaders’ outreach—matters most. At a September 2024 event in Boulder called the AI & the Church Hackathon, Gloo unveiled new AI tools called Data Engine, a content management system with built-in digital-rights safeguards, and Aspen, an early prototype of its “spiritually safe” chatbot, along with the faith-tuned language model powering that chatbot, known internally as CALLM (for “Christian-Aligned Large Language Model”).

More recently, the company released what it calls “Flourishing AI Standards,” which score large language models on their alignment with seven dimensions of well-being: relationships, meaning, happiness, character, finances, health, and spirituality. Co-developed with Barna Group and Harvard’s Human Flourishing Program, the benchmark draws on a thousand-plus-item test bank and the Global Flourishing Study, a $40 million, 22-nation project being carried out by the Harvard program, Baylor University’s Institute for Studies of Religion, Gallup, and the Center for Open Science.

Gelsinger calls the study “one of the most significant bodies of work around this question of values in decades.” It’s not yet clear how collecting information of this kind at such scale could ultimately affect the boundary between spiritual care and data commerce. One thing is certain, though: A rich vein of donation and funding could be at stake.

“Money’s already being spent here,” he said. “Donated capital in the US through the church is around $300 billion. Another couple hundred billion beyond that doesn’t go through the church. A lot of donors have capital out there, and we’re a generous nation in that regard. If you put the flourishing-related economics on the table, now we’re talking about $1 trillion. That’s significant economic capacity. And if we make that capacity more efficient, that’s big.” In secular terms, it’s a customer data life cycle. In faith tech, it could be a conversion funnel—one designed not only to save souls, but to shape them.

One of Gloo’s most visible partnerships was between 2022 and 2023 with the nonprofit He Gets Us, which ran a billion-dollar media campaign aimed at rebranding Jesus for a modern audience. The project underlined that while Gloo presents its services as tools for connection and support, their core functionality involves collecting and analyzing large amounts of congregational data. When viewers who saw the ads on social media or YouTube clicked through, they landed on prayer request forms, quizzes, and church match tools, all designed to gather personal details. Gloo then layered this raw data over Barna’s decades of behavioral research, turning simple inputs—email, location, stated interests—into what the company presented as multidimensional spiritual profiles. The final product offered a level of granularity no single congregation could achieve on its own.

Though Gloo still lists He Gets Us on its platform, the nonprofit Come Near, which has since taken over the campaign, says it has terminated Gloo’s involvement. Still, He Gets Us led to one of Gloo’s most prized relationships by sparking interest from the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, a 229-year-old denomination with deep historical roots in the abolitionist and civil rights movements. In 2023, the church formalized a partnership with Gloo, and in late 2024 it announced that all 1,600 of its US congregations—representing roughly 1.5 million members—would begin using the company’s State of Your Church dashboard.

In a 2024 press release issued by Gloo, AME Zion acknowledged that while the denomination had long tracked traditional metrics like membership growth, Sunday turnout, and financial giving, it had limited visibility into the deeper health of its communities.

“Until now, we’ve lacked the insight to understand how church culture, people, and congregations are truly doing,” said the Reverend J. Elvin Sadler, the denomination’s general secretary-auditor. “The State of Your Church dashboards will give us a better sense of the spirit and language of the culture (ethos), and powerful new tools to put in the hands of every pastor.”

The rollout marked the first time a major US denomination had deployed Gloo’s framework at scale. For Gloo, the partnership unlocked a real-time, longitudinal data stream from a nationwide religious network, something the company had never had before. It not only validated Gloo’s vision of data-driven ministry but also positioned AME Zion as what the company hopes will be a live test case, persuading other denominations to follow suit.

The digital supply chain

The digital infrastructure of modern churches often begins with intimacy: a prayer request, a small-group sign-up, a livestream viewed in a moment of loneliness. But beneath these pastoral touchpoints lies a sophisticated pipeline that increasingly mirrors the attention-economy engines of Silicon Valley.

Charles Kriel, a filmmaker who formerly served as a special advisor to the UK Parliament on disinformation, data, and addictive technology, has particular insight into that connection. Kriel has been working for over a decade on issues related to preserving democracy and countering digital surveillance. He helped write the UK’s Online Safety Act, joining forces with many collaborators, including the Nobel Peace Prize–winning journalist Maria Ressa and former UK tech minister Damian Collins, in an attempt to rein in Big Tech in the late 2010s.

His 2020 documentary film, People You May Know, investigated how data firms like Gloo and their partners harvest intimate personal information from churchgoers to build psychographic profiles, highlighting how this sensitive data is commodified and raising questions about its potential downstream uses.

“Listen, any church with an app? They probably didn’t build that. It’s white label,” Kriel says, referring to services produced by one company and rebranded by another. “And the people who sold it to them are collecting data.”

Many churches now operate within a layered digital environment, where first-party data collected inside the church is combined with third-party consumer data and psychographic segmentation before being fed into predictive systems. These systems may suggest sermons people might want to view online, match members with small groups, or trigger outreach when engagement drops.

In some cases, monitoring can even take the form of biometric surveillance.

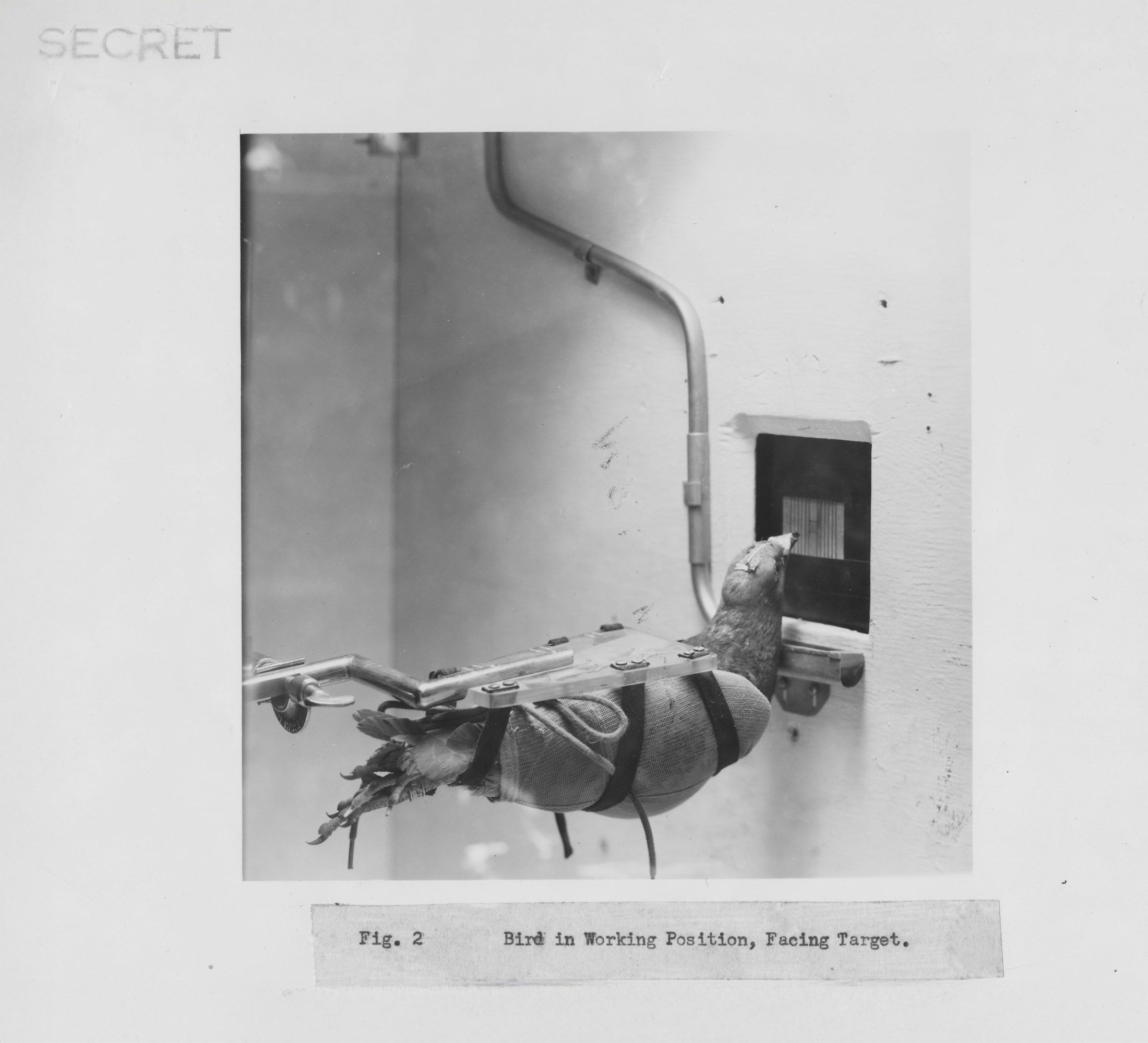

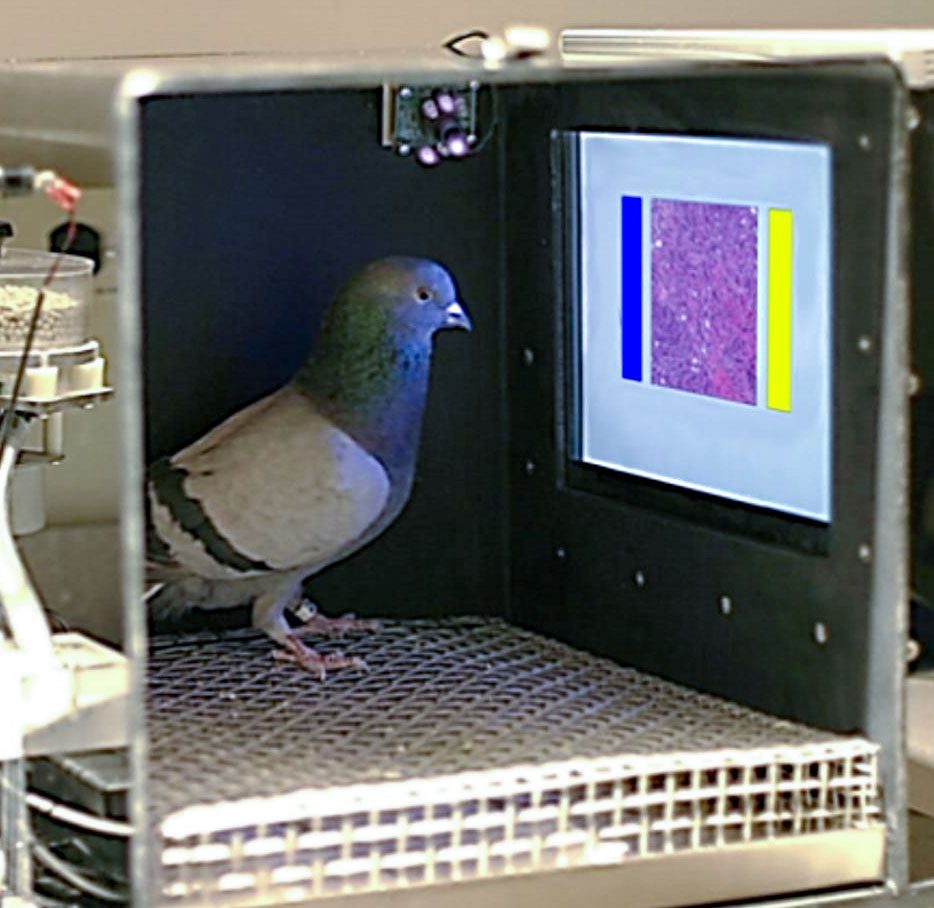

In 2014, an Israeli security-tech veteran named Moshe Greenshpan brought airport-grade facial recognition into church entryways. Face-Six, the surveillance suite from the company he founded in 2012, already protected banks and hospitals; its most provocative offshoot, FA6 Events (also known as “Churchix”), repurposes this technology for places of worship.

Greenshpan claims he didn’t originally set out to sell to churches. But over time, as he became increasingly aware of the market, he built FA6 Events as a bespoke solution for them. Today, Greenshpan says, it’s in use at over 200 churches worldwide, nearly half of them in the US.

In practice, FA6 transforms every entryway into a biometric checkpoint: an instant headcount, a security sweep, and a digital ledger of attendance, all incorporated into the familiar routine of Sunday worship.

When someone steps into an FA6-equipped place of worship, a discreet camera mounted at eye level springs to life. Behind the scenes, each captured image is run through a lightning-fast face detector that looks at the whole face. The subject’s cropped face is then aligned, resized, and rotated so the eyes sit on a perfect horizontal line before being fed into a compact neural network.

“To the best of my knowledge, no church notifies its congregants that it’s using facial recognition.”

Moshe Greenshpan, Israeli security-tech veteran

This onboard neural network quickly captures the features of a person’s face in a unique digital signature called an embedding, allowing for quick identification. These embeddings are compared with thousands of others that are already in the church’s local database, each one tagged with data points like a name, a membership role, or even a flag designating inclusion in an internal watch list. If the match is strong enough, the system makes an identification and records the person’s presence on the church’s secure server.

A congregation can pull full attendance logs, time-stamped entry records, and—critically—alerts whenever someone on a watch list walks through the doors. In this context, a watch list is simply a roster of photos, and sometimes names, of individuals a church has been asked (or elected) to screen out: past disruptors, those subject to trespass or restraining orders, even registered sex offenders. Once that list is uploaded into Churchix, the system instantly flags any match on arrival, pinging security teams or usher staff in real time. Some churches lean on it to spot longtime members who’ve slipped off the radar and trigger pastoral check-ins; others use it as a hard barrier, automatically denying entry to anyone on their locally maintained list.

None of this data is sent to the cloud; Greenshpan says the company is actively working on a cloud-based application. Instead, all face templates and logs are stored locally on church-owned hardware, encrypted so they can’t be read if someone gains unauthorized access.

Churches can export data from Churchix, he says, but the underlying facial templates remain on premises.

Still, Greenshpan admits, robust technical safeguards do not equal transparency.

“To the best of my knowledge,” he says, “no church notifies its congregants that it’s using facial recognition.”

If the tools sound invasive, the logic behind them is simple: The more the system knows about you, the more precisely it can intervene.

“Every new member of the community within a 20-mile radius—whatever area you choose—we’ll send them a flier inviting them to your church,” Gloo’s Gelsinger says.

It’s a tech-powered revival of the casserole ministry. The system pings the church when someone new moves in—“so someone can drop off cookies or lasagna when there’s a newborn in the neighborhood,” he says. “Or just say ‘Hey, welcome. We’re here.’”

Gloo’s back end automates follow-up, too: As soon as a pastor steps down from the pulpit after delivering a sermon, it can be translated into five languages, broken into snippets for small-group study, and repackaged into a draft discussion guide—ready within the hour.

Gelsinger sees the same approach extending to addiction recovery ministries. “We can connect other databases to help churches with recovery centers reach people more effectively,” he says.

But the data doesn’t stay within the congregation. It flows through customer relationship management (CRM) systems, application programming interfaces, cloud servers, vendor partnerships, and analytics firms. Some of it is used internally in efforts to increase engagement; the rest is repackaged as “insights” and resold to the wider faith-tech marketplace—and sometimes even to networks that target political ads.

“We measured prayer requests. Call it crazy. But it was like, ‘We’re sitting on mounds of information that could help us steward our people.’”

Matt Engel, Gloo

“There is a very specific thing that happens when churches become clients of Gloo,” says Brent Allpress, an academic based in Melbourne, Australia, who was a key researcher on People You May Know. Gloo gets access to the client church’s databases, he says, and the church “is strongly encouraged to share that data. And Gloo has a mechanism to just hoover that data straight up into their silo.”

This process doesn’t happen automatically; the church must opt in by pushing those files or connecting its church-management software system’s database to Gloo via API. Once it’s uploaded, however, all that first-party information lands in Gloo’s analytics engine, ready to be processed and shared with any downstream tools or partners covered by the church’s initial consent to the terms and conditions of its contract with the company.

“There are religious leaders at the mid and local level who think the use of data is good. They’re using data to identify people in need. Addicts, the grieving,” says Kriel. “And then you have tech people running around misquoting the Bible as justification for their data harvest.”

Matt Engel, who held the title executive director of ministry innovation at Gloo when Kriel’s film was made, acknowledged the extent of this harvest in the opening scene.

“We measured prayer requests. Call it crazy. But it was like, ‘We’re sitting on mounds of information that could help us steward our people,’” he said in an on-camera interview.

According to Engel—whom Gloo would not make available for public comment—uploading data from anonymous prayer requests to the cloud was Gloo’s first use case.

Powering third-party initiatives

But Gloo’s data infrastructure doesn’t end with its own platform; it also powers third-party initiatives.

Communio, a Christian nonprofit focused on marriage and family, used Gloo’s data infrastructure in order to launch “Communio Insights,” a stripped-down version of Gloo’s full analytics platform.

Unlike Gloo Insights, which provides access to hundreds of demographic, behavioral, health, and psychographic filters, Communio Insights focuses narrowly on relational metrics—indicators of marriage and family stress, involvement in small groups at church—and basic demographic data.

At the heart of its playbook is a simple, if jarring, analogy.

“If you sell consumer products of different sorts, you’re trying to figure out good ways to market that. And there’s no better product, really, than the gospel,” J.P. De Gance, the founder and president of Communio, said in People You May Know.

Communio taps Gloo’s analytics engine—leveraging credit histories, purchasing behavior, public voter rolls, and the database compiled by i360, an analytics company linked to the conservative Koch network—to pinpoint unchurched couples in key regions who are at risk of relationship strain. It then runs microtargeted outreach (using direct mail, text messaging, email, and Facebook Custom Audiences, a tool that lets organizations find and target people who have interacted with them), collecting contact info and survey responses from those who engage. All responses funnel back into Gloo’s platform, where churches monitor attendance, small-group participation, baptisms, and donations to evaluate the campaign’s impact.

Investigative research by Allpress reveals significant concerns around these operations.

In 2015, two nonprofits—the Relationship Enrichment Collaborative (REC), staffed by former Gloo executives, and its successor, the Culture of Freedom Initiative (now Communio), controlled by the Koch-affiliated nonprofit Philanthropy Roundtable—funded the development of the original Insights platform. Between 2015 and 2017, REC paid approximately $1.3 million to Gloo and $535,000 to Cambridge Analytica, the consulting firm notorious for harvesting Facebook users’ personal data and using it for political targeting before the 2016 election, to build and refine psychographic models and a bespoke digital ministry app powering Gloo’s outreach tools. Following REC’s closure, the Culture of Freedom Initiative invested another $375,000 in Gloo and $128,225 in Cambridge Analytica.

REC’s own 2016 IRS filing describes the work in terse detail: “Provide[d] digital micro-targeted marketing for churches and non-profit champions … using predictive modeling and centralized data analytics we help send the right message to the right couple at the right time based upon their desires and behaviors.”

On top of all this documented research, Allpress exposed another critical issue: the explicit use of sensitive health-care data.

He found that Gloo Insights combines over 2,000 data points—drawing on everything from nationwide credit and purchasing histories to church management records and Christian psychographic surveys—with filters that make it possible to identify people with health issues such as depression, anxiety, and grief. The result: Facebook Custom Audiences built to zero in on vulnerable individuals via targeted ads.

These ads invite people suffering from mental-health conditions into church counseling groups “as a pathway to conversion,” Allpress says.

These targeted outreach efforts were piloted in cities including Phoenix, Arizona; Dayton, Ohio; and Jacksonville, Florida. Reportedly, as many as 80% of those contacted responded positively, with those who joined a church as new members contributing financially at above-average rates. In short, Allpress found that pastoral tools had covertly exploited mental-health vulnerabilities and relationship crises for outreach that blurred the lines separating pastoral care, commerce, and implicit political objectives.

The legal and ethical vacuum

Developers of this technology earnestly claim that the systems are designed to enhance care, not exploit people’s need for it. They’re described as ways to tailor support to individual needs, improve follow-up, and help churches provide timely resources. But experts say that without robust data governance or transparency around how sensitive information is used and retained, well-intentioned pastoral technology could slide into surveillance.

In practice, these systems have already been used to surveil and segment congregations. Internal demos and client testimonials confirm that Gloo, for example, uses “grief” as an explicit data point: Churches run campaigns aimed at people flagged for recent bereavement, depression, or anxiety, funneling them into support groups and identifying them for pastoral check-ins.

Examining Gloo’s terms and conditions reveals further security and transparency concerns. From nearly a dozen documents, ranging from “click-through” terms for interactive services to master service agreements at the enterprise level, Gloo stitches together a remarkably consistent data-governance framework. Limits are imposed on any legal action by individual congregants, for example. The click-through agreement corrals users into binding arbitration, bars any class action suits or jury trials, and locks all disputes into New York or Colorado courts, where arbitration is particularly favored over traditional litigation. Meanwhile, its privacy statement carves out broad exceptions for service providers, data-enrichment partners, and advertising affiliates, giving them carte blanche to use congregants’ data as they see fit. Crucially, Gloo expressly reserves the right to ingest “health and wellness information” provided via wellness assessments or when mental-health keywords appear in prayer requests. This is a highly sensitive category of information that, for health apps, is normally covered by stringent medical-privacy rules like HIPAA.

In other words, Gloo is protected by sprawling legal scaffolding, while churches and individual users give up nearly every right to litigate, question data practices, or take collective action.

“We’re kind of in the Wild West in terms of the law,” says Adam Schwartz, the director of privacy litigation at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, the nonprofit watchdog that has spent years wrestling tech giants over data abuses and biometric overreach.

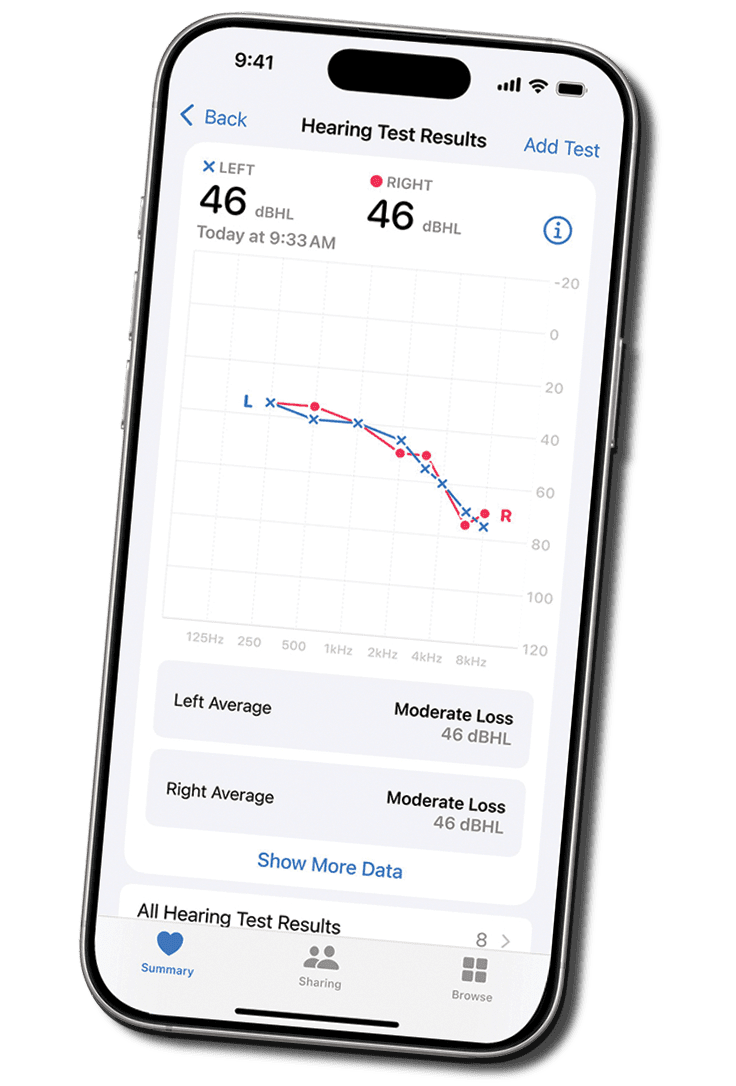

In the United States, biometric surveillance like that used by growing numbers of churches inhabits a legal twilight zone where regulation is thin, patchy, and often toothless. Schwartz points to Illinois as a rare exception for its Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA), one of the nation’s strongest such laws. The statute applies to any organization that captures biometric identifiers—including retina or iris scans, fingerprints, voiceprints, hand scans, facial geometry, DNA, and other unique biological information. It requires entities to post clear data-collection policies, obtain explicit written consent, and limit how long such data is retained. Failure to comply can expose organizations to class action lawsuits and steep statutory damages—up to $5,000 per violation.

But beyond Illinois, protections quickly erode. Though Texas and Washington also have biometric privacy statutes, their bark is stronger than their bite. Efforts to replicate Illinois’s robust protections have been made in over a dozen states—but none have passed. As a result, in much of the country, any checks on biometric surveillance depend more on voluntary transparency and goodwill than any clear legal boundary.

“There is a real potential for information gathered about a person [to] be used against them in their life outside the church.”

Emily Tucker, Center on Privacy & Technology at Georgetown Law

That’s especially problematic in the church context, says Emily Tucker, executive director of the Center on Privacy & Technology at Georgetown Law, who attended divinity school before becoming a legal scholar. “The necessity of privacy for the possibility of finding personal relationship to the divine—for engaging in rituals of worship, for prayer and penitence, for contemplation and spiritual struggle—is a fundamental principle across almost every religious tradition,” she says. “Imposing a surveillance architecture over the faith community interferes radically with the possibility of that privacy, which is necessary for the creation of sacred space.”

Tucker researches the intersection of surveillance, civil rights, and marginalized communities. She warns that the personal data being collected through faith-tech platforms is far from secure: “Because corporate data practices are so poorly regulated in this country, there are very few limitations on what companies that take your data can subsequently do with it.”

To Tucker, the risks of these platforms outweigh the rewards—especially when biometrics and data collected in a sacred setting could follow people into their daily lives. “Many religious institutions are extremely large and often perform many functions in a given community besides providing a space for worship,” she says. “Many churches, for example, are also employers or providers of social services. There is a real potential for information gathered about a person in their associational activities as a member of a church to then be used against them in their life outside the church.”

She points to government dragnet surveillance, the use of IRS data in immigration enforcement, and the vulnerability of undocumented congregants as examples of how faith-tech data could be weaponized beyond its intended use: “Religious institutions are putting the safety of those members at risk by adopting this kind of surveillance technology, which exposes so much personal information to potential abuse and misuse.”

Schwartz, too, says that any perceived benefits must be weighed carefully against the potential harms, especially when sensitive data and vulnerable communities are involved.

“Churches: Before doing this, you ought to consider the downside, because it can hurt your congregants,” he says.

With guardrails still scarce, though, faith-tech pioneers and church leaders are peering ever more deeply into congregants’ lives. Until meaningful oversight arrives, the faithful remain exposed to a gaze they never fully invited and scarcely understand.

In April, Gelsinger took the stage at a sold-out Missional AI Summit, a flagship event for Christian technologists that this year was organized around the theme “AI Collision: Shaping the Future Together.” Over 500 pastors, engineers, ethicists, and AI developers filled the hall, flashing badges with logos from Google DeepMind, Meta, McKinsey, and Gloo.

“We want to be part of a broader community … so that we’re influential in creating flourishing AI, technology as a force for good, AI that truly embeds the values that we care about,” Gelsinger said at the summit. He likened such tools to pivotal technologies in Christian history: the Roman roads that carried the gospel across the empire, or Martin Luther’s printing press, which shattered monolithic control over scripture. A Gloo spokesperson later confirmed that one of the company’s goals is to shape AI specifically to “contribute to the flourishing of people.”

“We’re going to see AI become just like the internet,” Gelsinger said. “Every single interaction will be infused with AI capabilities.”

He says Gloo is already mining data across the spectrum of human experience to fuel ever more powerful tools.

“With AI, computers adapt to us. We talk to them; they hear us; they see us for the first time,” he said. “And now they are becoming a user interface that fits with humanity.”

Whether these technologies ultimately deepen pastoral care or erode personal privacy may hinge on decisions made today about transparency, consent, and accountability. Yet the pace of adoption already outstrips the development of ethical guardrails. Now, one of the questions lingering in the air is not whether AI, facial recognition, and other emerging technologies can serve the church, but how deeply they can be woven into its nervous system to form a new OS for modern Christianity and moral infrastructure.

“It’s like standing on the beach watching a tsunami in slow motion,” Kriel says.

Gelsinger sees it differently.

“You and I both need to come to the same position, like Isaiah did,” he told the crowd at the Missional AI Summit. “‘Here am I, Lord. Send me.’ Send me, send us, that we can be shaping technology as a force for good, that we could grab this moment in time.”

Alex Ashley is a journalist whose reporting has appeared in Rolling Stone, the Atlantic, NPR, and other national outlets.