Early on a Sunday morning in September, a team of 12 sleep-deprived, jet-lagged researchers assembled at the world’s most remote airport. There, on Easter Island, some 2,330 miles off the coast of Chile, they were preparing for a unique chase: a race to catch a satellite’s last moments as it fell out of space and blazed into ash across the sky.

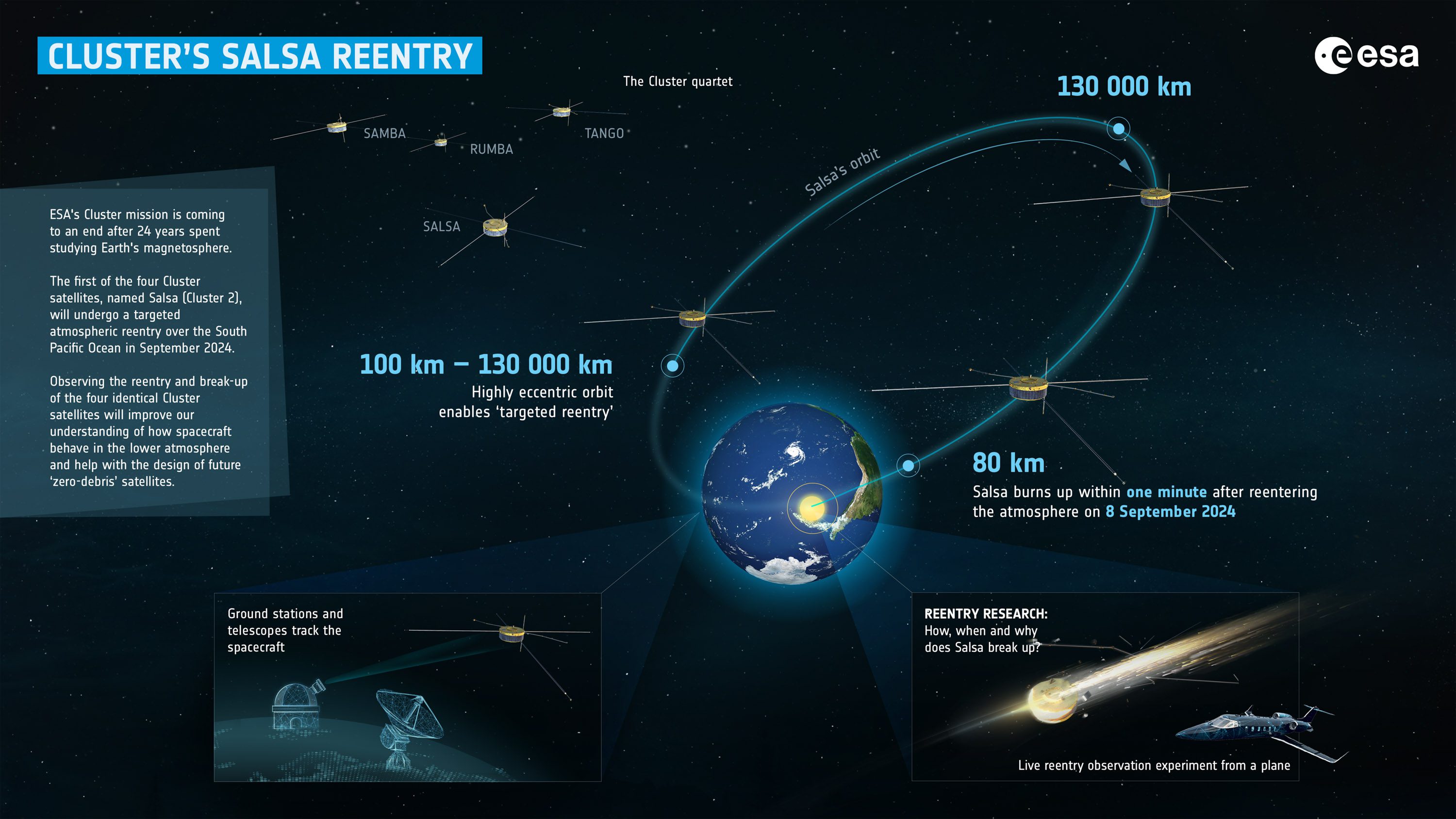

That spacecraft was Salsa, one of four satellites that were part of the European Space Agency (ESA) Cluster constellation. Salsa and its counterparts had been studying Earth’s magnetic field since the early 2000s, but its mission was now over. Months earlier, the spacecraft had been set on a spiral of death that would end with a fiery disintegration high up in Earth’s atmosphere about a thousand miles away from Easter Island’s coast.

Now, the scientists were poised to catch this reentry as it happened. Equipped with precise trajectory calculations from ESA’s ground control, the researchers took off in a rented business jet, with 25 cameras and spectrometers mounted by the windows. The hope was that they’d be able to gather priceless insights into the physical and chemical processes that occur when satellites burn up as they fall to Earth at the end of their missions.

Researchers were able to monitor the reentry of Cluster Salsa from a rented business jet.

This kind of study is growing more urgent. Some 15 years ago, barely a thousand satellites orbited our planet. Now the number has risen to about 10,000, and with the rise of satellite constellations like Starlink, another tenfold increase is forecast by the end of this decade. Letting these satellites burn up in the atmosphere at the end of their lives helps keep the quantity of space junk to a minimum. But doing so deposits satellite ash in the middle layers of Earth’s atmosphere. This metallic ash can harm the atmosphere and potentially alter the climate. Scientists don’t yet know how serious the problem is likely to be in the coming decades.

The ash from the reentries contains ozone-damaging substances. Modeling studies have shown that some of its components can also cool down Earth’s stratosphere, while others can warm it. Some worry that the metallic particles could even disrupt Earth’s magnetic field, obscure the view of Earth-observing satellites, and increase the frequency of thunderstorms.

“We need to see what kind of physics takes place up there,” says Stijn Lemmens, a senior analyst at ESA who oversaw the campaign. “If there are more [reentering] objects, there will be more consequences.”

A community of atmospheric scientists scattered all over the world is awaiting results from these measurements, hoping to fill major gaps in their understanding.

The Salsa reentry was only the fifth such observation campaign in the history of spaceflight. The previous campaigns, however, tracked much larger objects, like a 19-ton upper stage from an Ariane 5 rocket.

Cluster Salsa, at 550 kilograms, was quite tiny in comparison. And that makes it of special interest to scientists, because it’s spacecraft of this general size that will be increasingly crowding Earth orbit in the coming years.

The downside of mega-constellations

Most of the forecasted growth in satellite numbers is expected to come from satellites roughly the same size as Salsa: individual members of mega-constellations, designed to provide internet service with decent speed and latency to anyone, anywhere.

SpaceX’s Starlink is the biggest of these. Currently consisting of about 6,500 satellites, the fleet is expected to mushroom to more than 40,000 at some point in the 2030s. Other mega-constellations, including Amazon Kuiper, France-based E-Space, and the Chinese projects G60 and Guowang, are in the works. Each could encompass several thousand satellites, or even tens of thousands.

Mega-constellation developers don’t want their spacecraft to fly for two or three decades like their old-school, government-funded counterparts. They want to replace these orbiting internet routers with newer, better tech every five years, sending the old ones back into the atmosphere to burn up. The rockets needed to launch all those satellites emit their own cocktail of contaminants (and their upper stages also end their life burning up in the atmosphere).

The amount of space debris vaporizing in Earth’s atmosphere has more than doubled in the past few years, says Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who has built a second career as a leading space debris tracker..

“We used to see about 50 to 100 rocket stages reentering every year,” he says. “Now we’re looking at 300 a year.”

In 2019, some 115 satellites burned up in the atmosphere. As of late November, 2024 had already set a new record with 950 satellite reentries, McDowell says.

The mass of vaporizing space junk will continue to grow in line with the size of the satellite fleets. By 2033, it could reach 4,000 tons per year, according to estimates presented at a workshop called Protecting Earth and Outer Space from the Disposal of Spacecraft and Debris, held in September at the University of Southampton in the UK.

Crucially, most of the ash these reentries produce will remain suspended in the thin midatmospheric air for decades, perhaps centuries. But acquiring precise data about satellite burn-up is nearly impossible, because it takes place in territory that is too high for meteorological balloons to measure and too low for sounding instruments aboard orbiting satellites. The closest scientists can get is remote sensing of a satellite’s final moments.

Changing chemistry

None of the researchers aboard the business jet turned scientific laboratory that took off from Easter Island in September got to see the moment when Cluster Salsa burst into a fireball above the deep, dark waters of the Pacific Ocean. Against the bright daylight, the fleeting explosion appeared about as vivid as a midday full moon. The windows of the plane, however, were covered with dark fabric (to prevent light reflected from inside to skew the measurements), allowing only the camera lenses to peek out, says Jiří Šilha, CEO of Slovakia-based Astros Solutions, a space situational awareness company developing new techniques for space debris monitoring, which coordinated the observation campaign.

“We were about 300 kilometers [186 miles] away when it happened, far enough to avoid being hit by any remaining debris,” Šilha says. “It’s all very quick. The object reenters at a very high velocity, some 11 kilometers [seven miles] per second, and disintegrates 80 to 60 kilometers above Earth.”

The instruments collected measurements of the disintegration in the visible and near-infrared part of the light spectrum, including observations with special filters for detecting chemical elements including aluminum, titanium, and sodium. The data will help scientists reconstruct the satellite breakup process, working out the altitudes at which the incineration takes place, the temperatures at which it occurs, and the nature and quantity of the chemical compounds it releases.

The dusty leftovers of Cluster Salsa have by now begun their leisurely drift through the mesosphere and stratosphere—the atmospheric layers stretching at altitudes from 31 to 53 miles and 12 to 31 miles, respectively. Throughout their decades-long descent, these ash particles will interact with atmospheric gases, causing mischief, says Connor Barker, a researcher in atmospheric chemical modeling at University College London and author of a satellite air pollution inventory published in early October in the journal Scientific Data.

Satellite bodies and rocket stages are mostly made of aluminum, which burns into aluminum oxide, or alumina—a white, powdery substance known to contribute to ozone depletion. Alumina also reflects sunlight, which means it could alter the temperature of those higher atmospheric layers.

“In our simulations, we start to see a warming over time of the upper layers of the atmosphere that has several knock-on effects for atmospheric composition,” Barker says.

For example, some models suggest the warming could add moisture to the stratosphere. This could deplete the ozone layer and could cause further warming, which in turn would cause additional ozone depletion.

The extreme speeds of reentering satellites also produces “a shockwave that compresses nitrogen in the atmosphere and makes it react with oxygen, producing nitrogen oxides,” says McDowell. Nitrogen oxides, too, damage atmospheric ozone. Currently, 50% of the ozone depletion caused by satellite burn-ups and rocket launches comes from the effects of nitrogen oxides. The soot that rockets produce alters the atmosphere’s thermal balance too.

In some ways, high-altitude atmospheric pollution is nothing new. Every year, about 18,000 tons of meteorites vaporize in the mesosphere. Even 10 years from now, if all planned mega-constellations get developed, the quantity of natural space rock burning up during its fall to Earth will exceed the amount of incinerated space junk by a factor of five.

That, however, is no comfort to researchers like McDowell and Barker. Meteorites contain only trace amounts of aluminum, and their atmospheric disintegration is faster, meaning they produce less nitrogen oxide, says Barker.

“The amount of nitrogen oxides we’re getting [from satellite reentries and rocket launches] is already at the lower end of our yearly estimates of what the natural emissions of nitrogen oxides [from meteorites] are,” said Barker. “It’s certainly a concern, because we might soon be doing more to the atmosphere than naturally occurs.”

The annual amount of alumina from satellite reentries is also already approaching that arising from incinerated meteorites. Under current worse-case scenarios, the human-made contribution of this pollutant will be 10 times the amount from natural sources by 2040.

Impact on Earth?

What exactly does all this mean for life on Earth? At this stage, nobody’s certain. Studies focusing on various components of the air pollution cocktail from satellite and rocket activity are trickling in at a steady rate.

Barker says computer modeling puts the current contribution of the space industry to overall ozone depletion at a minuscule 0.1%. But how much this share will grow 10, 20, or 50 years from now, nobody knows. There are way too many uncertainties in this equation, including the size of the particles—which will affect how long they will take to sink—and the ratio of particles to gaseous by-products.

“We have to make a decision, as a society, whether we prioritize reducing space traffic or reducing emissions,” Barker says. “A lot of these increased reentry rates are because the global community is doing a really good job of cleaning up low-Earth-orbit space debris. But we really need to understand the environmental impact of those emissions so we can decide what is the best way for humanity to deal with all these objects in space.”

The disaster of 21st-century climate change was set in motion when humankind began burning fossil fuels in the mid-19th century. Similarly, it took 40 years for chlorofluorocarbons to eat a hole in Earth’s protective ozone layer. The contamination of Earth by so-called forever chemicals—per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances used in manufacturing nonstick coatings and firefighting foams—started in the 1950s. Researchers like McDowell are concerned the story may repeat yet again.

“Humanity’s activities in space have now gotten big enough that they are affecting the space environment in a similar way we have affected the oceans,” McDowell says. “The problem is that we’re making these changes without really understanding at what stage these changes will become concerning.”

Previous observation campaigns mostly analyzed the physical disintegration of reentering satellites. With the Cluster constellation, scientists hope to begin unraveling the chemical side of this elusive process. For researchers like Barker, that means finally getting data that could validate and further improve their models. The Cluster constellation will provide three more opportunities to fill the blanks in this environmental puzzle when the siblings of Salsa reenter in 2025 and 2026.

“The great thing with Cluster is that we have four satellites that are identical and that we know every detail about,” says Šilha. “It’s a scientist’s dream, because we can repeat the experiment and learn from every previous campaign.”