A short ferry ride from the port city of Yantai, on the northeast coast of China, sits Genghai No. 1, a 12,000-metric-ton ring of oil-rig-style steel platforms, advertised as a hotel and entertainment complex. On arrival, visitors step onto docks and climb up to reach a strange offshore facility—half cruise ship, half high-tech laboratory, all laid out around half a mile of floating walkways. Its highest point—the “glistening diamond” on Genghai No. 1’s necklace, according to China’s state news agency—is a seven-story visitor center, designed to look like a cartoon starfish.

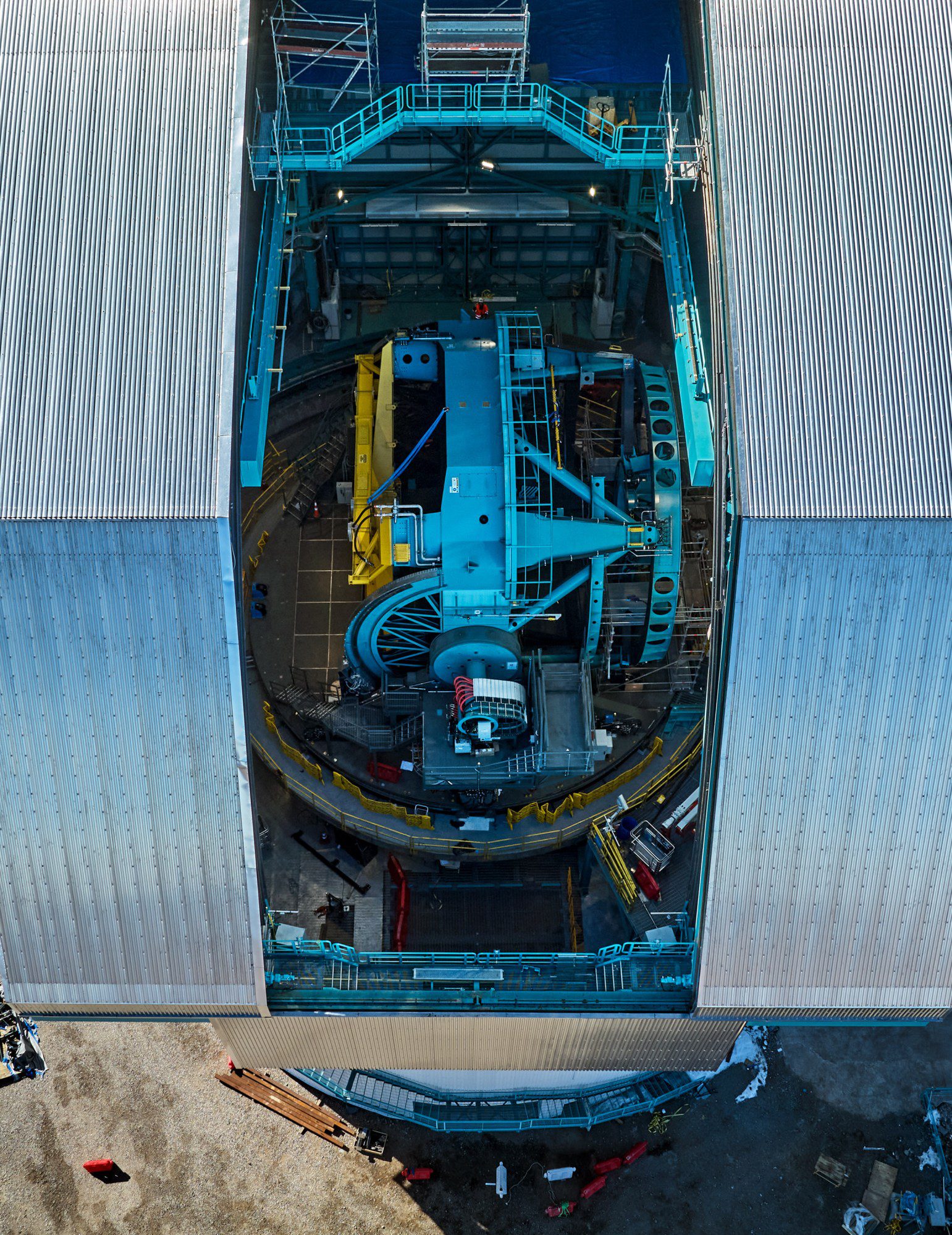

Jack Klumpp, a YouTuber from Florida, became one of the first 20,000 tourists to explore Genghai’s visitor center following its opening in May 2023. In his series I’m in China with Jack, Klumpp strolls around a water park cutely decorated in Fisher-Price yellow and turquoise, and indoors, he is excited to spot the hull of China’s deep-sea submersible Jiaolong. In reality, the sea here is only about 10 meters deep, and the submersible is only a model. Its journey into the ocean’s depths is an immersive digital experience rather than real adventure, but the floor of the sub rocks and shakes under his feet like a theme park ride.

Watching Klumpp lounge in Genghai’s luxe marine hotel, it’s hard to understand why anyone would build this tourist attraction on an offshore rig, nearly a mile out in the Bohai Strait. But the answer is at the other end of the walkway from Genghai’s tourist center, where on a smaller, more workmanlike platform, he’s taught how to cast a worm-baited line over the edge and reel in a hefty bream.

Genghai is in fact an unusual tourist destination, one that breeds 200,000 “high-quality marine fish” each year, according to a recent interview in China Daily with Jin Haifeng, deputy general manager of Genghai Technology Company, a subsidiary of the state-owned shipbuilder Shandong Marine Group. Just a handful of them are caught by recreational fishers like Klumpp. The vast majority are released into the ocean as part of a process known as marine ranching.

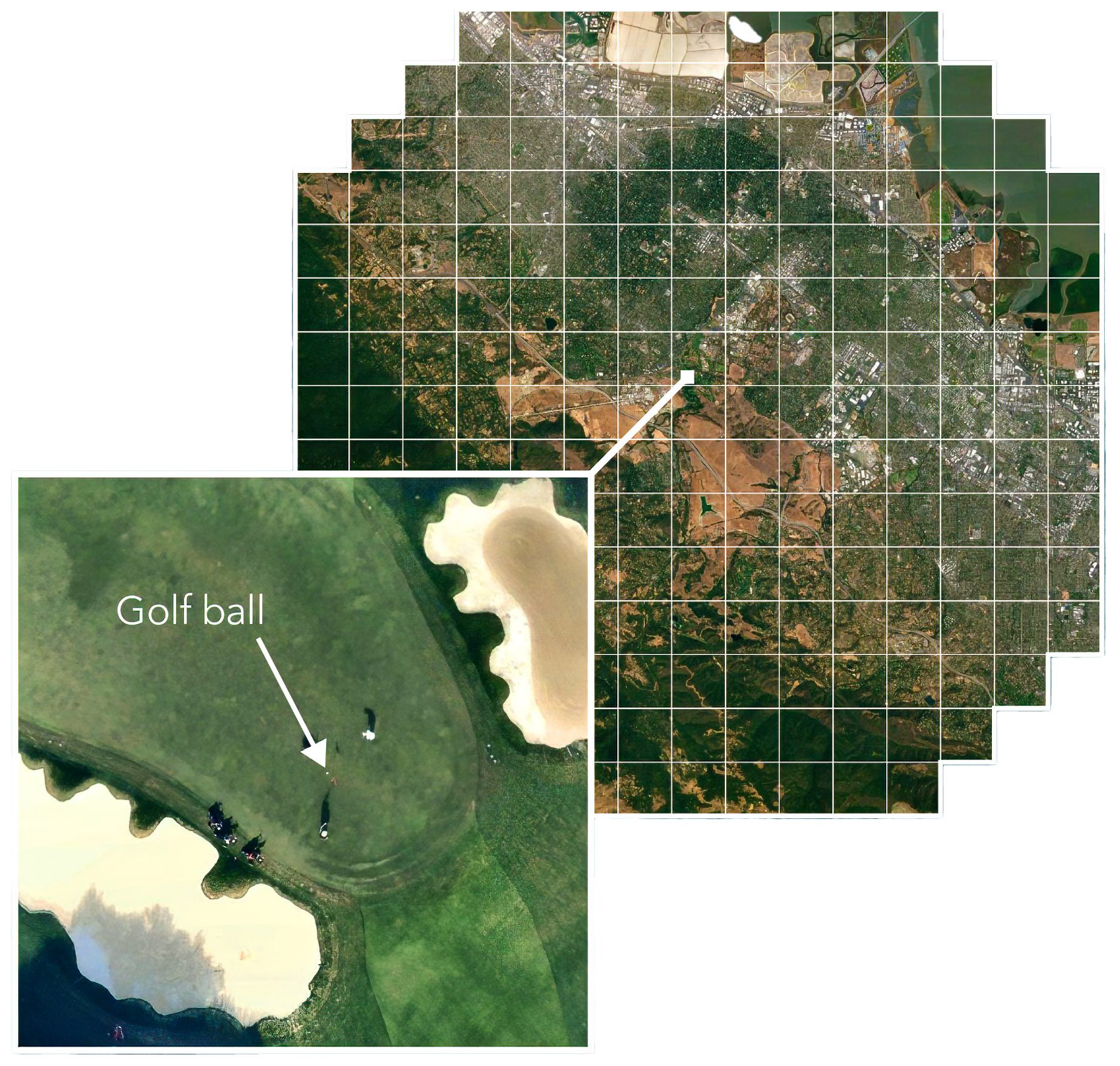

Since 2015, China has built 169 “national demonstration ranches”—including Genghai No. 1—and scores of smaller-scale facilities, which collectively have laid 67 million cubic meters of artificial reefs and planted an area the size of Manhattan with seagrass, while releasing at least 167 billion juvenile fish and shellfish into the ocean.

The Chinese government sees this work as an urgent and necessary response to the bleak reality that fisheries are collapsing both in China and worldwide, with catches off China’s coast declining 18% in less than a decade. In the face of that decline, marine ranches could offer an enticing win-win: a way to restore wild marine ecosystems while boosting fishery hauls.

Marine ranches could offer an enticing win-win: a way to restore wild marine ecosystems while boosting fishery hauls. But before China invests billions more dollars into these projects, it must show it can get the basics right.

Genghai, which translates as “Sea Harvest,” sits atop what Jin calls an “undersea ecological oasis” constructed by developers. In the middle of the circular walkway, artificial marine habitats harbor shrimp, seaweed, and fish, including the boggle-eyed Korean rockfish and a fish with a parrot-like beak, known as the spotted knifejaw.

The facility is a next-generation showcase for the country’s ambitious plans, which call for 200 pilot projects by 2025. It’s a 5G-enabled, AI-equipped “ecological” ranch that features submarine robots for underwater patrols and “intelligent breeding cages” that collect environmental data in near-real time to optimize breeding by, for example, feeding fish automatically.

In an article published by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, China’s top science institute, one high-ranking fisheries expert sketches out plans for a seductive tech-driven future where production and conservation go hand in hand: Ecological ranches ring the coastline, seagrass meadows and coral reefs regrow around them, and autonomous robots sustainably harvest mature seafood.

But now, Chinese researchers say, is the time to take stock of lessons learned from the rapid rollout of ranching to date. Before the country invests billions more dollars into similar projects in the coming years, it must show it can get the basics right.

What, exactly, is a marine ranch?

Developing nations have historically faced a trade-off between plundering marine resources for development and protecting ecosystems for future generations, says Cao Ling, a professor at Xiamen University in eastern China. When growing countries take more than natural ecosystems can replenish, measures like seasonal fishing bans have been the traditional way to allow fisheries to recover. Marine ranching offers an alternative to restricting fishing—a way to “really synergize environmental, economic, and social development goals,” says Cao—by actively increasing the ocean’s bounty.

It’s now a “hot topic” in China, says Cao, who grew up on her family’s fish farm before conducting research at the University of Michigan and Stanford. In fact, “marine ranching” has become such a buzzword that it can be hard to tell what it actually means, encompassing as it does flagship facilities like Genghai No. 1 (which merge scientific research with industrial-scale aquaculture pens, recreational fishing amenities, and offshore power) and a baffling array of structures including deep-sea floating wind farms with massive fish-farming cages and 100,000-ton “mobile marine ranches”—effectively fish-breeding aircraft carriers. There are even whole islands, like the butterfly-shaped Wuzhizhou on China’s tropical south coast, that have been designated as ranching areas.

To understand what a marine ranch is, it’s easiest to come back to the practice’s roots. In the early 1970s, California, Oregon, Washington, and Alaska passed laws to allow construction of facilities aimed at repairing stocks of salmon after the rivers where they traditionally bred had been decimated by pollution and hydroelectric dams. The idea was essentially twofold: to breed fish in captivity and to introduce them into safe nurseries in the Pacific. Since 1974, when the first marine ranches in the US were built off the coast of California and Oregon, ranchers have constructed artificial habitats, usually concrete reef structures, that proponents hoped could provide nursery grounds where both valuable commercial stocks and endangered marine species could be restored.

Today, fish farming is a $200 billion industry that has had a catastrophic environmental impact, blighting coastal waters with streams of fish feces, pathogens, and parasites.

Marine ranching has rarely come close to fulfilling this potential. Eight of the 11 ranches that opened in the US in the 1970s were reportedly shuttered by 1990, their private investors having struggled to turn a profit. Meanwhile, European nations like Norway spent big on attempts to restock commercially valuable species like cod before abandoning the efforts because so few introduced fish survived in the wild. Japan, which has more ranches than any other country, made big profits with scallop ranching. But a long-term analysis of Japan’s policies estimated that all other schemes involving restocking the ocean were unprofitable. Worse, it found, releasing docile, lab-bred fish into the wild could introduce genetically damaging traits into the original population.

Today, marine ranching is often considered a weird offshoot of conventional fish farming, in which fish of a single species are fed intensively in small, enclosed pens. This type of feedlot-style aquaculture has grown massively in the last half-century. Today it’s a $200 billion industry and has had a catastrophic environmental impact, blighting coastal waters with streams of fish feces, pathogens, and parasites.

Yet coastal nations have not been discouraged by the mediocre results of marine ranching. Many governments, especially in East Asia, see releasing millions of young fish as a cheap way for governments to show their support for hard-hit fishing communities, whose livelihoods are vanishing as fisheries teeter on the edge of collapse. At least 20 countries continue to experiment with diverse combinations of restocking and habitat enhancement—including efforts to transplant coral, reforest mangroves, and sow seagrass meadows.

Each year at least 26 billion juvenile fish and shellfish, from 180 species, are deliberately released into the world’s oceans—three for every person on the planet. Taken collectively, these efforts amount to a great, ongoing, and little-noticed experiment on the wild marine biome.

China’s big bet

China, with a population of 1.4 billion people, is the world’s undisputed fish superpower, home to the largest fishing fleet and more than half the planet’s fish farms. The country also overwhelms all others in fish consumption, using as much as the four next-largest consumers—the US, the European Union, Japan, and India—combined and then doubled. But decades of overfishing, compounded by runaway pollution from industry and marine aquaculture, have left its coastal fisheries depleted.

Around many Chinese coastal cities like Yantai, there is a feeling that things “could not be worse,” says Yong Chen, a professor at Stony Brook University in New York. In the temperate northern fishing grounds of the Bohai and Yellow Seas, stocks of wild fish such as the large yellow croaker—a species that’s critically endangered—have collapsed since the 1980s. By the turn of the millennium, the Bohai, a densely inhabited gulf 100 miles east of Beijing, had lost most of its large sea bass and croaker, leaving fishing communities to “fish down” the food chain. Fishing nets came up 91% lighter than they did in the 1950s, in no small part because heavy industry and this region’s petrochemical plants had left the waters too dirty to support healthy fish populations.

As a result, over the past three decades China has instituted some of the world’s strictest seasonal fishing bans; recently it has even encouraged fishermen to find other jobs. But fish populations continue to decline, and fishing communities worry for their future.

Marine ranching has received a big boost from the highest levels of government; it’s considered an ideal test case for President Xi Jinping’s “ecological civilization” agenda, a strategy for environmentally sustainable long-term growth. Since 2015, ranching has been enshrined in successive Five-Year Plans, the country’s top-level planning documents—and ranch construction has been backed by an initial investment of ¥11.9 billion ($1.8 billion). China is now on track to release 30 billion juvenile fish and shellfish annually by 2025.

So far, the practice has produced an unlikely poster child: the sea cucumber. A spiky, bottom-dwelling animal that, like Japan’s scallops, doesn’t move far from release sites, it requires little effort for ranchers to recapture. Across northern China, sea cucumbers are immensely valuable. They are, in fact, one of the most expensive dishes on menus in Yantai, where they are served chopped and braised with scallions.

Some ranches have experimented with raising multiple species, including profitable fish like sea bass and shellfish like shrimp and scallops, alongside the cucumber, which thrives in the waste that other species produce. In the northern areas of China, such as the Bohai, where the top priority is helping fishing communities recover, “a very popular [mix] is sea cucumbers, abalone, and sea urchin,” says Tian Tao, chief scientific research officer of the Liaoning Center for Marine Ranching Engineering and Science Research at Dalian Ocean University.

Designing wild ecosystems

Today, most ranches are geared toward enhancing fishing catches and have done little to deliver on ecological promises. According to Yang Hongsheng, a leading marine scientist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the mix of species that has so far been introduced has been “too simple” to produce a stable ecosystem, and ranch builders have paid “inadequate attention” to that goal.

Marine ranch construction is typically funded by grants of around ¥20 million ($2.8 million) from China’s government, but ranches are operated by private firms. These companies earn revenue by producing seafood but have increasingly cultivated other revenue streams, like tourism and recreational fishing, which has boomed in recent years. So far, this owner-operator model has provided few incentives to look beyond proven methods that closely resemble aquaculture—like Genghai No. 1’s enclosed deep-sea fishing cages—and has done little to encourage contributions to ocean health beyond the ranch’s footprint. “Many of the companies just want to get the money from the government,” says Zhongxin Wu, an associate professor at Dalian Ocean University who works with Tian Tao.

Making ranches more sustainable and ecologically sound will require a rapid expansion of basic knowledge about poorly studied marine species, says Stony Brook’s Yong Chen. “For a sea cucumber, the first thing you need to know is its life history, right? How they breed, how they live, how they die,” he says. “For many key marine species, we have few ideas what temperature or conditions they prefer to breed and grow in.”

Chinese universities are world leaders in applied sciences, from agricultural research to materials science. But fundamental questions aren’t always easy to answer in China’s “quite unique” research and development environment, says Neil Loneragan, president of the Malaysia-based Asian Fisheries Society and a professor emeritus of marine science at Murdoch University in Australia.

The central government’s controlling influence on the development of ranching, Loneragan says, means researchers must walk a tightrope between their two bosses: the academic supervisor and the party chief. Marine biologists want to understand the basics, “but researchers would have to spin that so that it’s demonstrating economic returns to industry and, hence, the benefits to the government from investment,” he says.

Many efforts aim to address known problems in the life cycles of captive-bred fish, such as inadequate breeding rates or the tough survival odds for young fish when they reach the ocean. Studies have shown that fish in these early life stages are particularly vulnerable to environmental fluctuations like storms and recent ocean heat waves.

One of the most radical solutions, which Zhongxin Wu is testing, would improve their fitness before they’re released from breeding tanks into the wild. Currently, Wu says, fish are simply scooped up in oxygenated plastic bags and turned loose in ocean nurseries, but there it becomes apparent that many are weak or lacking in survival skills. In response, his team is developing a set of “wild training” tools. “The main method is swimming training,” he says. In effect, the juvenile fish are forced to swim against a current, on a sort of aquatic treadmill, to help acclimate them to the demands of the wild. Another technique, he says, involves changing the water temperature and introducing some other species to prepare them for seagrass and kelp forests they’ll meet in the world outside.

Wu says better methods of habitat enhancement have the greatest potential to increase the effectiveness of marine ranching. Today, most ranches create undersea environments using precast-concrete structures that are installed under 20 meters of water, often with a rough surface to support the growth of coral or algae. The typical Chinese ranch aims for 30,000 cubic meters of artificial reefs; in the conservation-focused ranching area around Wuzhizhou Island, for instance, 1,000 cast-concrete reef structures were dropped around the tropical island’s shores. Fish populations have multiplied tenfold in the last decade.

This is by far the most expensive part of China’s ranching program. According to a national evaluation coauthored by Cao Ling, 87% of China’s first $1 billion investment has gone to construct artificial reefs, with a further 5% spent on seagrass and seaweed restoration. These costs have brought both questions about the effectiveness of the efforts and a drive for innovation. Across China, some initial signs suggest that the enhancements are making a difference: Sites with artificial reefs were found to have a richer mix of commercially important species and higher biomass than adjacent sites. But Tian and Wu are investigating new approaches, including custom 3D-printed structures for endangered fish. On trial are bungalow-size steel ziggurats with wide openings for yellowtail kingfish—a large, predatory fish that’s prized for sashimi—and arcs of barrel-vaulted concrete, about waist height, for sea cucumbers. In recent years, structures have been specifically designed in the shape of pyramids, to divert ocean currents into oceanic “upwellings.” Nutrients that typically settle on the seafloor are instead ejected back up toward the surface. “That attracts prey for high-level predators,” says Loneragan, including giant tuna-like species that fetch high prices at restaurants.

Has China found a workable model?

So will China soon be relying on marine ranches to restock the seas? We still don’t have anywhere near enough data to say. The Qingdao Marine Conservation Society, an environmental NGO, is one of the few independent organizations systematically assessing ranches’ track records and has, says founder Songlin Wang, “failed to find sufficient independent and science-based research results that can measurably verify most marine ranches’ expected or claimed environmental and social benefits.”

One answer to the data shortfall might be the kind of new tech on display at Genghai No. 1, where robotic patrols and subsea sensors feed immediately into a massive dashboard measuring water quality, changes in the ocean environment, and fish behavior. After decades as a fairly low-tech enterprise, ranching in China has been adopting such new technologies since the beginning of the latest Five-Year Plan in 2021. The innovations promise to improve efficiency, reduce costs, and make ranches more resilient to climate fluctuations and natural disasters, according to the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

But Yong Chen, whose lab at Stony Brook partners with Chinese researchers, is skeptical that researchers are gathering and sharing the right data. “The problem is, yes, there’s this visualization. So what?” he says. “[Marine ranching companies] are willing to invest money into this kind of infrastructure, create that kind of big screen, and people will walk in and say ‘Wow, look at that!’” he adds. “Yeah, it’s beautiful. It definitely will impress the leadership. Important people will give you money for that. But as a scientist, my question to you is: How can it help you inform your decision-making process next year?”

Will China soon be relying on marine ranches to restock the seas? We still don’t have anywhere near enough data to say.

“Data sharing is really difficult in China,” says Cao Ling. Most data produced by private companies remains in their servers. But Cao and Chen say that governments—local or central—could facilitate more open data sharing in the interest of guiding ranch design and policy.

But China’s central government is convinced by what it has seen and plans to scale up investment. Tian, who leads the government committee on marine ranching, says he has recently learned that the next Ten-Year Plan will aim to increase the number of pilot ranches from 200 to 350 by 2035. Each one is expected to be backed by ¥200 million ($28 million)—10 times the typical current investment. Specific policies are due to be announced next year, but he expects that ranches will no longer be funded as standalone facilities. Instead, grants will likely be given to cities like Dalian and Yantai, which can plan across land and sea and find ways to link commercial fishing with power generation and tourism while cutting pollution from industry.

Tian has an illustration that aims to visualize the coming tech-driven ecological ranching system, a sort of “marine ranching 3.0”: a sea cove monitored by satellites and restored to such good health that orcas have returned to its fish-filled waters. It’s a near-utopian image seemingly ripped from a 1960s issue of Popular Science. There’s even stranger research that aims to see if red sea bream like the one Jack Klumpp caught can be conditioned like Pavlov’s dogs—in this case to flock to the sound of a horn, so the ocean’s harvest would literally swim into nets at the press of a button.

So far China’s marine ranching program remains far from any of this, despite the isolated signs of success. But ultimately what matters most is to find a “balance point” between commerce and sustainability, says Cao. Take Genghai No. 1: “It’s very pretty!” she says with a laugh. “And it costs a lot for the initial investment.” If such ranches are going to contribute to China’s coming “ecological civilization,” they’ll have to prove they are delivering real gains and not just sinking more resources into a dying ocean.

Matthew Ponsford is a freelance reporter based in London.