Chinese AI chatbots want to be your emotional support

This story first appeared in China Report, MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology developments in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

Chinese ChatGPT-like bots are having a moment right now.

As I reported last week, Baidu became the first Chinese tech company to roll out its large language model—called Ernie Bot—to the general public, following a regulatory approval from the Chinese government. Previously, access required an application or was limited to corporate clients. You can read more about the news here.

I have to admit the Chinese public has reacted more passionately than I had expected. According to Baidu, the Ernie Bot mobile app reached 1 million users in the 19 hours following the announcement, and the model responded to more than 33.42 million user questions in 24 hours, averaging 23,000 questions per minute.

Since then, four more Chinese companies—the facial-recognition giant SenseTime and three young startups, Zhipu AI, Baichuan AI, and MiniMax—have also made their LLM chatbot products broadly available. But some more experienced players, like Alibaba and iFlytek, are still waiting for the clearance.

Like many others, I downloaded the Ernie Bot app last week to try it out. I was curious to find out how it’s different from its predecessors like ChatGPT.

What I noticed first was that Ernie Bot does a lot more hand-holding. Unlike ChatGPT’s public app or website, which is essentially just a chat box, Baidu’s app has a lot more features that are designed to onboard and engage new users.

Under Ernie Bot’s chat box, there’s an endless list of prompt suggestions—like “Come up with a name for a baby” and “Generating a work report.” There’s another tab called “Discovery” that displays over 190 pre-selected topics, including gamified challenges (“Convince the AI boss to raise my salary”) and customized chatting scenarios (“Compliment me”).

It seems to me that a major challenge for Chinese AI companies is that now, with government approval to open up to the public, they actually need to earn users and keep them interested. To many people, chatbots are a novelty right now. But that novelty will eventually wear off, and the apps need to make sure people have other reasons to stay.

One clever thing Baidu has done is to include a tab for user-generated content in the app. In the community forum, I can see the questions other users have asked the app, as well as the text and image responses they got. Some of them are on point and fun, while others are way off base, but I can see how this inspires users to try to input prompts themselves and work to improve the answers.

Another feature that caught my attention was Ernie Bot’s efforts to introduce role-playing.

One of the top categories on the “Discovery” page asks the chatbot to respond in the voice of pre-trained personas including Chinese historical figures like the ancient emperor Qin Shi Huang, living celebrities like Elon Musk, anime characters, and imaginary romantic partners. (I asked the Musk bot who it is; it answered: “I am Elon Musk, a passionate, focused, action-oriented, workaholic, dream-chaser, irritable, arrogant, harsh, stubborn, intelligent, emotionless, highly goal-oriented, highly stress-resistant, and quick-learner person.”

I have to say they do not seem to be very well trained; “Qin Shi Huang” and “Elon Musk” both broke character very quickly when I asked them to comment on serious matters like the state of AI development in China. They just gave me bland, Wikipedia-style answers.

But the most popular persona—already used by over 140,000 people, according to the app—is called “the considerate elder sister.” When I asked “her” what her persona is like, she answered that she’s gentle, mature, and good at listening to others. When I then asked who trained her persona, she responded that she was trained by “a group of professional psychology experts and artificial-intelligence developers” and “based on analysis of a large amount of language and emotional data.”

“I won’t answer a question in a robotic way like ordinary AIs, but I will give you more considerate support by genuinely caring about your life and emotional needs,” she also told me.

I’ve noticed that Chinese AI companies have a particular fondness for emotional-support AI. Xiaoice, one of the first Chinese AI assistants, made its name by allowing users to customize the perfect romantic partner. And another startup, Timedomain, left a trail of broken hearts this year when it shut down its AI boyfriend voice service. Baidu seems to be setting up Ernie Bot for the same kind of use.

I’ll be watching this slice of the chatbot space grow with equal parts intrigue and anxiety. To me, it’s one of the most interesting possibilities for AI chatbots. But this is more challenging than writing code or answering math problems; it’s an entirely different task to ask them to provide emotional support, act like humans, and stay in character all the time. And if the companies do pull it off, there will be more risks to consider: What happens when humans actually build deep emotional connections with the AI?

Would you ever want emotional support from an AI chatbot? Tell me your thoughts at zeyi@technologyreview.com.

Catch up with China

1. The mysterious advanced chip in Huawei’s newly released smartphone has sparked many questions and much speculation about China’s progress in chip-making technology. (Washington Post $)

2. Meta took down the largest Chinese social media influence campaign to date, which included over 7,000 Facebook accounts that bashed the US and other adversaries of China. Like its predecessors, the campaign failed to attract attention. (New York Times $)

3. Lawmakers across the US are concerned about the idea of China buying American farmland for espionage, but actual land purchase data from 2022 shows that very few deals were made by Chinese entities. (NBC News)

4. A Chinese government official was sentenced to life in prison on charges of corruption, including fabricating a Bitcoin mining company’s electricity consumption data. (Cointelegraph)

5. Terry Gou, the billionaire founder of Foxconn, is running as an independent candidate in Taiwan’s 2024 presidential election. (Associated Press)

6. The average Chinese citizen’s life span is now 2.2 years longer thanks to the efforts in the past decade to clean up air pollution. (CNN)

7. Sinopec, the major Chinese oil company, predicts that gasoline demand in China will peak in 2023 because of the surging demand for electric vehicles. (Bloomberg $)

8. Chinese sextortion scammers are flooding Twitter comment sections and making the site almost unusable for Chinese speakers. (Rest of World)

Lost in translation

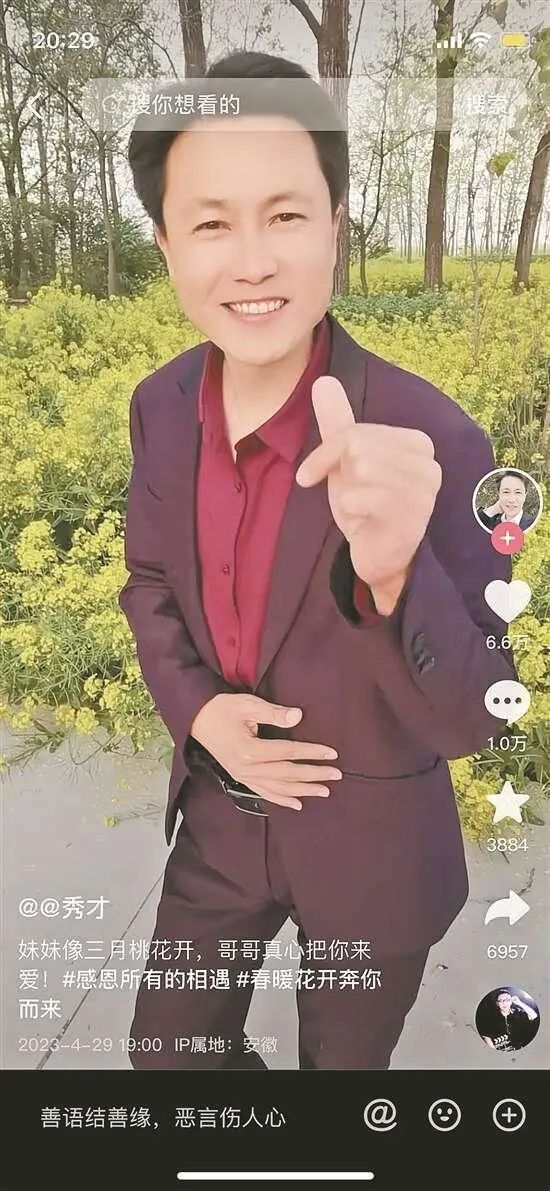

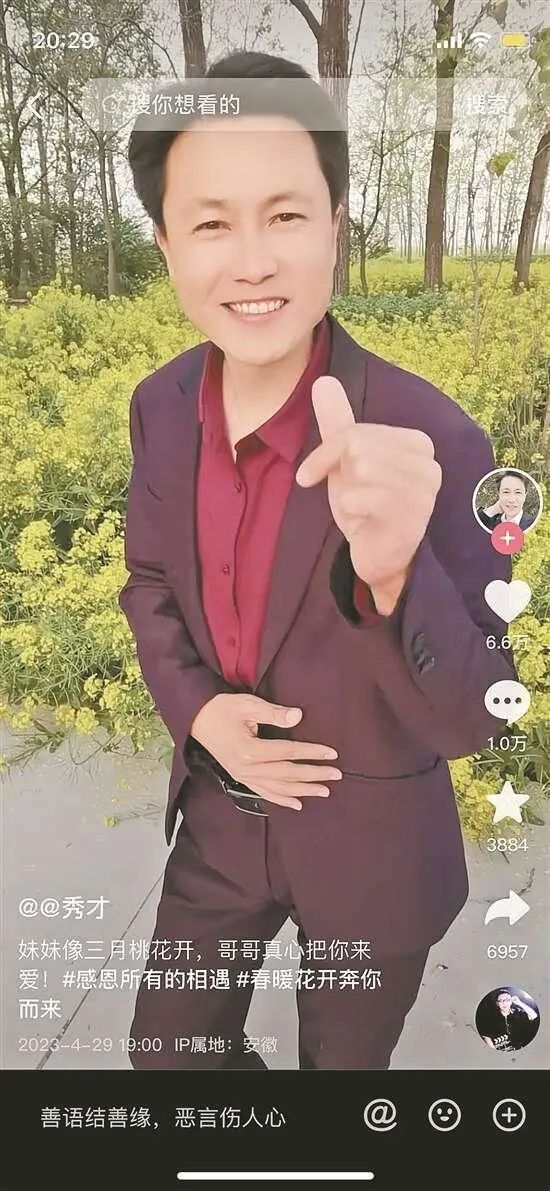

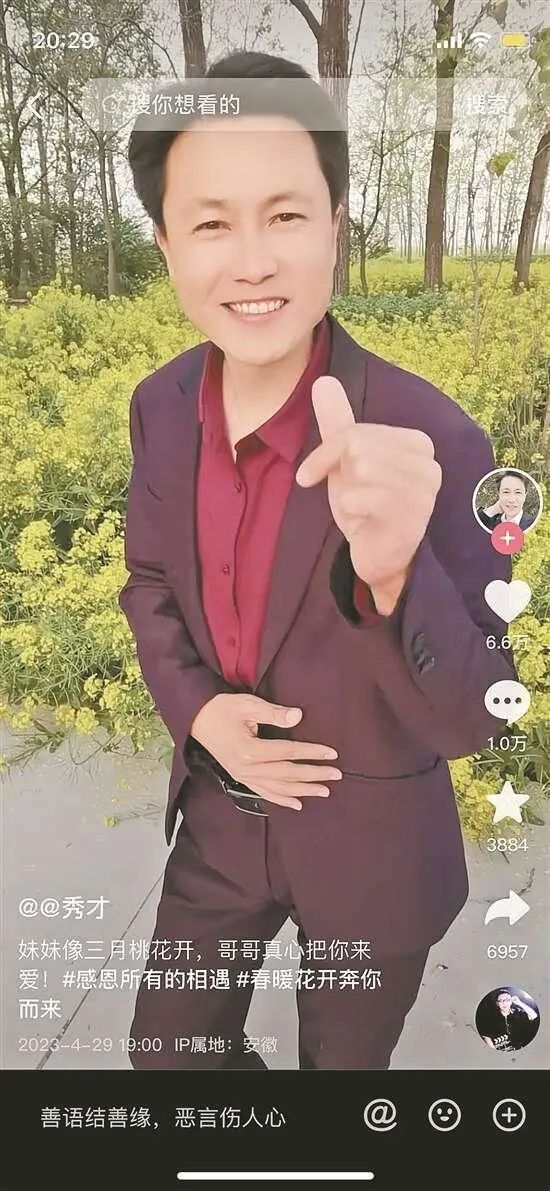

The favorite influencer of Chinese grandmas just got banned from social media. “Xiucai,” a 39-year-old man from Maozhou city, posted hundreds of videos on Douyin where he acts shy in China’s countryside, subtly flirts with the camera, and lip-synchs old songs. While the younger generations find these videos cringe-worthy, his look and style amassed him a large following among middle-aged and senior women. He attracted over 12 million followers in just over two years, over 70% of whom were female and nearly half older than 50. In May, a 72-year-old fan took a 1,000-mile solo train ride to Xiucai’s hometown just so she could meet him in real life.

But last week, his account was suddenly banned from Douyin, which said Xiucai had violated some platform rules. Local taxation authorities in Maozhou said he was reported for tax evasion, but the investigation hasn’t concluded yet, according to Chinese publication National Business Daily. His disappearance made more young social media users aware of his cultish popularity. As those in China’s silver generation learn to use social media and even become addicted to it, they have also become a lucrative target for content creators.

One more thing

Forget about bubble tea. The trendiest drink in China this week is a latte mixed with baijiu, the potent Chinese liquor. Named “sauce-flavored latte,” the eccentric invention is a collaboration between Luckin Coffee, China’s largest cafe chain, and Kweichow Moutai, China’s most famous liquor brand. News of its release lit up Chinese social media because it sounds like an absolute abomination, but the very absurdity of the idea makes people want to know what it actually tastes like. Dear readers in China, if you’ve tried it, can you let me know what it was like? I need to know, for research reasons.