It’s still a challenge to spot Chinese state media social accounts

This story first appeared in China Report, MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology developments in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

It’s no secret that Chinese state-owned media are active on Western social platforms, but sometimes they take a covert approach and distance themselves from China, perhaps to reach more unsuspecting audiences.

Such operations have been found to target Chinese- and English-speaking users in the past. Now, a study published last week has discovered another network of Twitter accounts that seems to be obscuring its China ties. This time, it’s made up of Spanish-language news accounts targeting Latin America.

Sandra Quincoses, an intelligence advisor at the cybersecurity research firm Nisos, found three accounts posting news about Paraguay, Chile, and Costa Rica on Twitter. The accounts seem to be associated with three Chinese-language newspapers based in those countries. All three are subsidiaries of a Brazil-based Chinese community newspaper called South America Overseas Chinese Press Network.

Very few of the posts are overtly political. The content, which is often the same in all three accounts, usually consists of Spanish-language news about Chinese culture, Chinese viral videos, and one panda post every few days.

The problematic part, Quincoses says, is that they obscure the sources of their news posts. The accounts often post articles from China News Service (CNS), one of the most prominent Chinese state-owned publications, but they do so without attribution.

Sometimes the accounts will go halfway toward attribution. They might specify, for example, that the news is from “Twitter •mundo_china” without actually tagging the @mundo_China, an account affiliated with the Chinese state broadcaster.

“When you do not mention Twitter accounts with the proper “@” format, tools that collect from Twitter to do analysis don’t pick up on that,” says Quincoses. As a result, these accounts can fly under the radar of social network analysis tools, making it hard for researchers to associate them with accounts that are clearly related to the Chinese government.

It’s unclear whether these accounts and the newspapers they belong to are controlled directly by Chinese state media. But as obscure as they are, there are real Chinese diplomats following them, suggesting official approval. And one government outlet—CNS—is working closely with these newspapers.

CNS is directly owned by the Chinese Communist Party’s United Front Work Department. In the 1990s, it started fostering ties with outlets aimed at Chinese immigrant communities around the world.

Today, CNS and these immigrant community newspapers often co-publish articles, and CNS invites executives from the publications to visit China for a conference called the Forum on the Global Chinese Language Media. Some of these publications have often been accused of being controlled or even owned by CNS, the main example being the China Press, a California-based publication.

As media outlets enter the digital age, there is more evidence that these overseas diaspora publications have close ties with CNS. Sinoing (also known as Beijing Zhongxin Chinese Technology Development or Beijing Zhongxin Chinese Media Service), a wholly owned subsidiary of CNS, is the developer behind 36 such news websites across six continents, the Nisos report says. It has also made mobile apps for nearly a dozen such outlets, including the South America Overseas Chinese Press Network, which owns the three Twitter accounts. These apps are also particularly invasive when it comes to data gathering, the Nisos report says.

At the same time, in a hiring post for an overseas social media manager, CNS explicitly wrote in the job description that the work involves “setting up and managing medium-level accounts and covert accounts on overseas social platforms.”

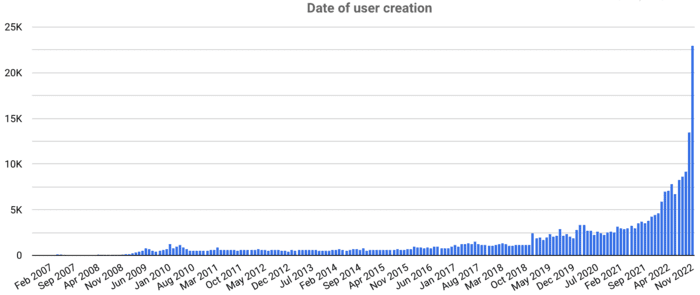

It’s unclear whether the three Twitter accounts identified in this report are operated by CNS. If this is indeed a covert operation, the job has been done a little too well. Though they post several times a day, two of the accounts have followers in the single digits, while the other one has around 80 followers—including a few real Chinese diplomats to Spanish-speaking countries. Most of the posts have received minimal engagement.

The lack of success is consistent with China’s social media propaganda campaigns in the past. This April, Google identified over 100,000 accounts in “a spammy influence network linked to China,” but the majority of accounts had 0 subscribers, and over 80% of their videos had fewer than 100 views. Twitter and Facebook identified similar unsuccessful attempts in the past, too.

Of all the state actors she has studied, Quincoses says, China is the least direct when it comes to the intentions of such networks. They could be playing the long game, she says.

Or maybe they just haven’t figured out how to run covert Twitter accounts effectively.

According to Quincoses, these accounts were never among those Twitter labeled as government-funded media (a practice it dropped in April). This could be related to the limited traction the accounts got, or to the efforts they made to obscure their ties to Chinese state media.

As other platforms are emerging to take on Twitter, Chinese state-owned publications have begun to appear on them too. Xinhua News Service, China’s main state-owned news agency, has several accounts on Mastodon, one of which still posts regularly. And CGTN, the country’s state broadcaster, has an account on Threads that already has over 50,000 followers.

Responding to an inquiry from the Australian government, Meta said it plans to add labels for government-affiliated media soon. But can it target accounts like these that are trying (and failing) to promote China’s image? They may be small fish now, but it’s better to catch them early before they grow influential enough, like their more successful peers from Russia.

Do social media users need better tools to sort out what might be government-affiliated media? Tell me at zeyi@technologyreview.com.

Catch up with China

1. John Kerry, the US climate envoy, is visiting China to restart climate negotiations between the two countries. (CNN)

2. Executives of American chip companies, including Intel, Qualcomm, and Nvidia, are flocking to Washington to talk the administration out of more curbs against China. (Bloomberg $)

3. The Taiwanese chip giant TSMC is known for harsh workplace rules imposed to protect its trade secrets, including a ban on Apple Watches at work. Now, facing difficulty attracting talent, the company is relaxing those rules. (The Information $)

4. A Kenyan former content moderator for TikTok is threatening to sue the app and its local content moderation contractor, claiming PTSD and unfair dismissal. (Time)

5. Amazon sellers say their whole stores—including images, descriptions, and even product testing certificates—have been cloned by sellers on Temu, the rising cross-broader e-commerce platform from China. (Wired $)

6. Microsoft says Chinese hackers accessed the email accounts of Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo and other US officials in June, but they didn’t get any classified email. (New York Times $)

7. Badiucao, an exiled Chinese political cartoonist, is carefully navigating security risks as he tours his artworks around the world. (The Spectator)

Lost in translation

As image-making AIs become increasingly popular, some Chinese fashion brands are ditching real human models and opting for AI-generated ones. Chinese publication AI Lanmeihui reports that some Stable Diffusion users are charging Chinese vendors 15 RMB (about $2) for an AI-generated product catalogue photo. A specialized website (still built on the open-source Stable Diffusion algorithm) allows vendors to customize the look of the model for just $2.80. Meanwhile, the cost of a photography session with a human model usually comes down to about $14 per photo, according to professional model Zhao Xuan. AI has already started taking jobs from human models, Zhao said, and it’s promoting unrealistic beauty standards in the industry. “The emergence of AI models is popularizing extreme aesthetics and causing professional models to have body shame,” she said. And the technology is still in its early stages: commercially available services often take more than a week, and the quality of the result is variable.

One more thing

Some Chinese workers are being asked to use AI tools but find that the process of tinkering with them takes too much time. As a result, they’ve been faking using ChatGPT or Midjourney and instead doing their job the old-fashioned way. One social media copywriter managed to mimic ChatGPT’s writing style so well that his boss was fully convinced it had to be the work of an AI. The boss then showed it around the office, asking other colleagues to generate articles like this too, according to the Chinese publication Jingzhe Qingnian.