How ASML took over the chipmaking chessboard

On a drab Monday morning in San Jose, California, at the drab San Jose Convention Center, attendees of the SPIE Advanced Lithography and Patterning Conference filed into the main ballroom until all the seats were taken and the crowd began to line the walls along the back and sides of the room. The convention brings together people who work in the chip industry from all over the world. And on this cool February morning, they had gathered to hear tech industry luminaries extol the late Gordon Moore, Intel’s cofounder and first CEO.

Craig Barrett, also a former CEO of Intel, paid tribute, as did the legendary engineer Burn-Jeng Lin, a pioneer of immersion lithography, a patterning technology that enabled the chip industry to continue moving forward about 20 years ago. Mostly the speeches tended toward reflections on Moore himself—testaments to his genius, accomplishments, and humanity. But the last speaker of the morning, Martin van den Brink, took a different tone, more akin to a victory lap than a eulogy. Van den Brink is the outgoing co-president and CTO of ASML, the Dutch company that makes the machines that in turn let manufacturers produce the most advanced computer chips in the world.

Moore’s Law holds that the number of transistors on an integrated circuit doubles every two years or so. In essence, it means that chipmakers are always trying to shrink the transistors on a microchip in order to pack more of them in. The cadence has been increasingly hard to maintain now that transistor dimensions measure in a few nanometers. In recent years ASML’s machines have kept Moore’s Law from sputtering out. Today, they are the only ones in the world capable of producing circuitry at the density needed to keep chipmakers roughly on track. It is the premise of Moore’s Law itself, van den Brink said, that drives the industry forward, year after year.

To showcase how big an achievement it had been to maintain Moore’s Law since he joined ASML in 1984, van den Brink referred to the rice and chessboard problem, in which the number of grains of rice—a proxy for transistors—is doubled on each successive square. The exponential growth in the number of transistors that can be crammed on a chip since 1959 means that a single grain of rice back then has now become the equivalent of three ocean tankers, each 240 meters long, full of rice. It’s a lot of rice! Yet Moore’s Law compels the company—compels all of the technology industry—to keep pushing forward. Each era of computing, most recently AI, has brought increased demands, explained van den Brink. In other words, while three tankers full of rice may seem like a lot, tomorrow we’re going to need six. Then 12. Then 24. And so on.

ASML’s technology, he assured the gathering, would be there to meet the demands, thanks to the company’s investment in creating tools capable of making ever finer features: the extreme-ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines it rolled out widely in 2017, the high-numerical-aperture (high-NA) EUV machines it is rolling out now, and the hyper-NA EUV machines it has sketched out for the future.

The tribute may have been designed for Gordon Moore, but at the end of van den Brink’s presentation the entire room rose to give him a standing ovation. Because if Gordon Moore deserves credit for creating the law that drove the progress of the industry, as van den Brink says, van den Brink and ASML deserve much of the credit for ensuring that progress remains possible.

Yet that also means the pressure is on. ASML has to try and stay ahead of the demands of Moore’s Law. It has to continue making sure chipmakers can keep doubling the amount of rice on the chessboard. Will that be possible? Van den Brink sat down with MIT Technology Review to talk about ASML’s history, its legacy, and what comes next.

Betting big on an unwieldy wavelength

ASML is such an undisputed leader in today’s chip ecosystem that it’s hard to believe the company’s market dominance really only dates back to 2017, when its EUV machine, after 17 years of development, upended the conventional process for making chips.

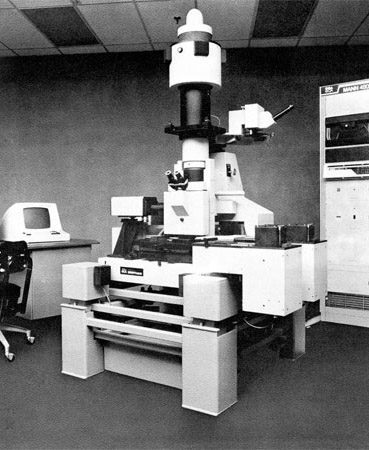

Since the 1960s, photolithography has made it possible to pack computer chips with more and more components. The process involves crafting small circuits by guiding beams of light through a series of mirrors and lenses and then shining that light on a mask, which contains a pattern. Light conveys the chip design, layer by layer, eventually building circuits that form the computational building blocks of everything from smartphones to artificial intelligence.

Photolithographers have a limited set of tools at their disposal to make smaller designs, and for decades, the type of light used in the machine was the most critical. In the 1960s, machines used beams of visible light. The smallest features this light could draw on the chip were fairly large—a bit like using a marker to draw a portrait.

Then manufacturers began using smaller and smaller wavelengths of light, and by the early 1980s, they could make chips with ultraviolet light. Nikon and Canon were the industry leaders. ASML, founded in 1984 as a subsidiary of Philips in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, was just a small player.

The way van den Brink tells it, he arrived at the company almost by accident. Philips was one of a few technology companies in Holland. When he began his career there in 1984 and was looking into the various opportunities at the company, he became intrigued by a photo of a lithography machine.

“I looked at the picture and I said, ‘It has mechanics, it has optics, it has software—this looks like a complex machine. I will be interested in that,” van den Brink told MIT Technology Review. “They said, well, you can do it, but the company will not be part of Philips. We are creating a joint venture with ASM International, and after the joint venture, you will not be part of Philips. I said yes because I couldn’t care less. And that’s how it began.”

When van den Brink joined in the 1980s, little about ASML made the company stand out from other major lithography players at the time. “We didn’t sell a substantial amount of systems until the ’90s. And we almost went bankrupt several times in that period,” van den Brink says. “So for us there was only one mission: to survive and show a customer that we could make a difference.”

By 1995, it had a strong enough foothold in the industry against competitors Nikon and Canon to go public. But all lithography makers were fighting the same battle to create smaller components on chips.

If you could have eavesdropped on a meeting at ASML in the late 1990s about this predicament, you might have heard chatter about an idea called extreme-ultraviolet (EUV) lithography—along with concerns that it might never work). By that point, with pressure to condense chips beyond current capabilities, it seemed as if everyone was chasing EUV. The idea was to pattern chips with an even smaller wavelength of light (ultimately just 13.5 nanometers). To do so, ASML would have to figure out how to create, capture, and focus this light—processes that had stumped researchers for decades—and build a supply chain of specialized materials, including the smoothest mirrors ever produced. And to make sure the price point wouldn’t drive away its customers.

Canon and Nikon were also pursuing EUV, but the US government denied them a license to participate in the consortium of companies and US national labs researching it. Both subsequently dropped out. Meanwhile ASML acquired the fourth major company pursuing EUV, SVG, in 2001. By 2006 it had shipped only two EUV prototype machines to research facilities, and it took until 2010 to ship one to a customer. Five years later, ASML warned in its annual report that EUV sales remained low, that customers weren’t eager to adopt the technology given its slow speed on the production line, and that if the pattern continued, it could have “material” effects on the business given the significant investment.

Yet in 2017, after an investment of $6.5 billion in R&D over 17 years, ASML’s bet began to pay off. That year the company shipped 10 of its EUV machines, which cost over $100 million each, and announced that dozens more were on backorder. EUV machines went to the titans of semiconductor manufacturing—Intel, Samsung, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC)—and a small number of others. With a brighter light source (meaning less time needed to impart patterns), among other improvements, the machines were capable of faster production speeds. The leap to EUV finally made economic sense to chipmakers, putting ASML essentially in a monopoly position.

Chris Miller, a history professor at Tufts University and author of Chip War: The Fight for the World’s Most Critical Technology, says that ASML was culturally equipped to see those experiments through. “It’s a stubborn willingness to invest in technology that most people thought wouldn’t work,” he told MIT Technology Review. “No one else was betting on EUV, because the development process was so long and expensive. It involves stretching the limits of physics, engineering, and chemistry.”

A key factor in ASML’s growth was its control of the supply chain. ASML acquired number of the companies it relies on, like Cymer, a maker of light sources. That strategy of pointedly controlling power in the supply chain extended to ASML’s customers, too. In 2012, it offered shares to its three biggest customers, which were able to maintain market dominance of their own in part because of the elite manufacturing power of ASML’s machines.

“Our success depends on their success,” van den Brink told MIT Technology Review.

It’s also a testament to ASML’s dominance that it is for the most part no longer allowed to sell its most advanced systems to customers in China. Though ASML still does business in China, in 2019, following pressure from the Trump administration, the Dutch government began imposing restrictions on ASML’s exports of EUV machines to China. Those rules were tightened further just last year and now also impose limits on some of the company’s deep-ultraviolet (DUV) machines, which are used to make less highly advanced chips than EUV systems.

Van den Brink says the way world leaders are now discussing lithography was unimaginable when the company began: “Our prime minister was sitting in front of Xi Jinping, not because he was from Holland—who would give a shit about Holland. He was there because we are making EUV.”

Just a few years after the first EUV machines shipped, ASML would face its second upheaval. Around the start of the pandemic, interest and progress in the field of artificial intelligence sent demand for computing power skyrocketing. Companies like OpenAI needed ever more powerful computer chips and by late 2022 the frenzy and investment in AI began to boil over.

By that time, ASML was closing in on its newest innovation. Having already adopted a smaller wavelength of light (and realigned the entire semiconductor industry to it in the process), it now turned its attention to the other lever in its control: numerical aperture. That’s the measure of how much light a system can focus, and if ASML could increase it, the company’s machines could print even smaller components.

Doing so meant myriad changes. ASML had to source an even larger set of mirrors from its supplier Carl Zeiss, which had to be made ultra-smooth. Zeiss had to build entirely new machines, the sole purpose of which was to measure the smoothness of mirrors destined for ASML. The aim was to reduce the number of costly repercussions the change would have on the rest of the supply chain, like the companies that make reticles containing the designs of the chips.

In December of 2023, ASML began shipping the first of its next-generation EUV device, a high-NA machine, to Intel’s facility in Hillsboro, Oregon. It’s an R&D version, and so far the only one in the field. It took seven planes and 50 trucks to get it to Intel’s plant, and installation of the machine, which is larger than a double-decker bus, will take six months.

The high-NA machines will only be needed to produce the most precise layers of advanced chips for the industry; the designs on many others will still be printed using the previous generation of EUV machines or older DUV machines.

ASML has received orders for high-NA machines from all its current EUV customers. They don’t come cheap: reports put the cost at $380 million. Intel was the first customer to strike, ordering the first machine available in early 2022. The company, which has lost significant market share to competitor TSMC, is betting that the new technology will give it a new foothold in the industry, even though other chipmakers will eventually have access to it too.

“There are obvious benefits to Intel for being the first,” Miller says. “There are also obvious risks.” Sorting out which chips to use these machines for and how to get its money’s worth out of them will be a challenge for the company, according to Miller.

The launch of these machines, if successful, might be seen as the crowning achievement of van den Brink’s career. But he is already moving on to what comes next.

The future

The next big idea for ASML, according to van den Brink and other company executives who spoke with MIT Technology Review, is hyper-NA technology. The company’s high-NA machines have a numerical aperture of .55. Hyper-NA tools would have a numerical aperture higher than 0.7. What that ultimately means is that hyper NA, if successful, will allow the company to create machines that let manufacturers shrink transistor dimensions even more—assuming that researchers can devise chip components that work well at such small dimensions. As it was with EUV in the early 2000s, it is still uncertain whether hyper NA is feasible—if nothing else, it could be cost prohibitive. Yet van den Brink projects cautious confidence. It is likely, he says, that the company will ultimately have three offerings available: low NA, high NA, and—if all goes well—hyper NA.

“Hyper NA is a bit more risky,” says van den Brink. “We will be more cautious and more cost sensitive in the future. But if we can pull this off, we have a winning trio which takes care of all the advanced manufacturing for the foreseeable future.”

Yet although today everyone is banking on ASML to keep pushing the industry forward, there is speculation that a competitor could emerge from China. Van den Brink was dismissive of this possibility, citing the gap in even last-generation lithography.

“SMEE are making DUV machines, or at least claim they can,” he told MIT Technology Review, referring to a company that makes the predecessor to EUV lithography technology, and pointed out that ASML still has the dominant market share. The political pressures could mean more progress for China. But getting to the level of complexity involved in ASML’s suite of machines, with low, high, and hyper NA is another matter, he says: “I feel quite comfortable that this will be a long time before they can copy that.”

Miller, from Tufts University, is confident that Chinese companies will eventually develop these sorts of technologies on their own, but agrees that the question is when. “If it’s in a decade, it will be too late,” he says.

The real question, perhaps, is not who will make the machines, but whether Moore’s Law will hold at all. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang has already declared it dead. But when asked what he thought might eventually cause Moore’s Law to finally stall out, van den Brink rejected the premise entirely.

“There’s no reason to believe this will stop. You won’t get the answer from me where it will end,” he said. “It will end when we’re running out of ideas where the value we create with all this will not balance with the cost it will take. Then it will end. And not by the lack of ideas.”

He had struck a similar posture during his Moore tribute at the SPIE conference, exuding confidence. “I’m not sure who will give the presentation 10 years from now,” he said, going back to his rice analogy. “But my successors,” he claimed, “will still have the opportunity to fill the chessboard.”

This story was updated to clarify information about ASML’s operations in China.