How to have a child in the digital age

When the journalist and culture critic Amanda Hess got pregnant with her first child, in 2020, the internet was among the first to know. “More brands knew about my pregnancy than people did,” she writes of the torrent of targeted ads that came her way. “They all called me mama.”

The internet held the promise of limitless information about becoming the perfect parent. But at seven months, Hess went in for an ultrasound appointment and everything shifted. The sonogram looked atypical. As she waited in an exam room for a doctor to go over the results, she felt the urge to reach for her phone. Though it “was ludicrous,” she writes, “in my panic, it felt incontrovertible: If I searched it smart and fast enough, the internet would save us. I had constructed my life through its screens, mapped the world along its circuits. Now I would make a second life there too.” Her doctor informed her of the condition he suspected her baby might have and told her, “Don’t google it.”

Unsurprisingly, that didn’t stop her. In fact, she writes, the more medical information that doctors produced—after weeks of escalating tests, her son was ultimately diagnosed with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome—the more digitally dependent she became: “I found I was turning to the internet, as opposed to my friends or my doctors, to resolve my feelings and emotions about what was happening to me and to exert a sense of external control over my body.”

But how do we retain control over our bodies when corporations and the medical establishment have access to our most personal information? What happens when humans stop relying on their village, or even their family, for advice on having a kid and instead go online, where there’s a constant onslaught of information? How do we make sense of the contradictions of the internet—the tension between what’s inherently artificial and the “natural” methods its denizens are so eager to promote? In her new book, Second Life: Having a Child in the Digital Age (Doubleday, 2025), Hess explores these questions while delving into her firsthand experiences with apps, products, algorithms, online forums, advertisers, and more—each promising an easier, healthier, better path to parenthood. After welcoming her son, who is now healthy, in 2020 and another in 2022, Hess is the perfect person to ask: Is that really what they’re delivering?

In your book, you write, “I imagined my [pregnancy] test’s pink dye spreading across Instagram, Facebook, Amazon. All around me, a techno-corporate infrastructure was locking into place. I could sense the advertising algorithms recalibrating and the branded newsletters assembling in their queues. I knew that I was supposed to think of targeted advertising as evil, but I had never experienced it that way.” Can you unpack this a bit?

Before my pregnancy, I never felt like advertising technology was particularly smart or specific. So when my Instagram ads immediately clocked my pregnancy, it came as a bit of a surprise, and I realized that I was unaware of exactly how ad tech worked and how vast its reach was. It felt particularly eerie in this case because in the beginning my pregnancy was a secret that I kept from everyone except my spouse, so “the internet” was the only thing that was talking to me about it. Advertising became so personalized that it started to feel intimate, even though it was the opposite of that—it represented the corporate obliteration of my privacy. The pregnancy ads reached me before a doctor would even agree to see me.

Though your book was written before generative AI became so ubiquitous, I imagine you’ve thought about how it changes things. You write, “As soon as I got pregnant, I typed ‘what to do when you get pregnant’ in my phone, and now advertisers were supplying their own answers.” What do the rise of AI and the dramatic changes in search mean for someone who gets pregnant today and goes online for answers?

I just googled “what to do when you get pregnant” to see what Google’s generative AI widget tells me now, and it’s largely spitting out commonsensical recommendations: Make an appointment to see a doctor. Stop smoking cigarettes. That is followed by sponsored content from Babylist, an online baby registry company that is deeply enmeshed in the ad-tech system, and Perelel, a startup that sells expensive prenatal supplements.

So whether or not the search engine is using AI, the information it’s providing to the newly pregnant is not particularly helpful or meaningful.

app

The internet “made me feel like I had some kind of relationship with my phone, when all it was really doing was staging a scene of information that it could monetize.”

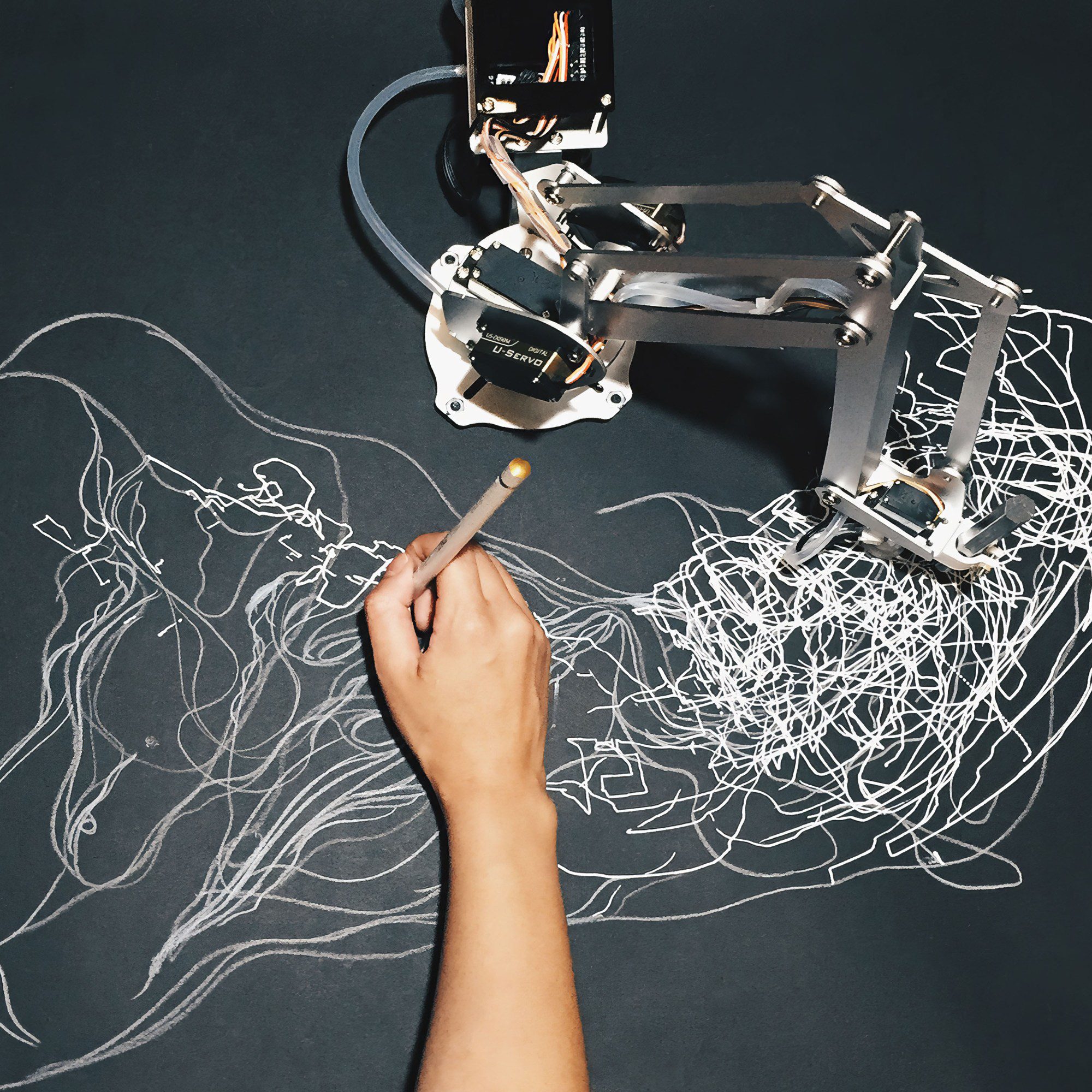

For me, the oddly tantalizing thing was that I had asked the internet a question and it gave me something in response, as if we had a reciprocal relationship. So even before AI was embedded in these systems, they were fulfilling the same role for me—as a kind of synthetic conversation partner. It made me feel like I had some kind of relationship with my phone, when all it was really doing was staging a scene of information that it could monetize.

As I wrote the book, I did put some pregnancy-related questions to ChatGPT to try to get a sense of the values and assumptions that are encoded in its knowledge base. I asked for an image of a fetus, and it provided this garishly cartoonish, big-eyed cherub in response. But when I asked for a realistic image of a postpartum body, it refused to generate one for me! It was really an extension of something I write about in the book, which is that the image of the fetus is fetishized in a lot of these tech products while the pregnant or postpartum body is largely erased.

You have this great—but quite sad—quote from a woman on TikTok who said, “I keep hearing it takes a village to raise a child. Do they just show up, or is there a number to call?”

I really identified with that sentiment, while at the same time being suspicious of this idea that can we just call a hotline to conjure this village?

I am really interested that so many parent-focused technologies sell themselves this way. [The pediatrician] Harvey Karp says that the Snoo, this robotic crib he created, is the new village. The parenting site Big Little Feelings describes its podcast listeners as a village. The maternity clothing brand Bumpsuit produces a podcast that’s actually called The Village. By using that phrase, these companies are evoking an idealized past that may never have existed, to sell consumer solutions. A society that provides communal support for children and parents is pitched as this ancient and irretrievable idea, as opposed to something that we could build in the future if we wanted to. It will take more than just, like, ordering something.

And the benefit of many of those robotic or “smart” products seems a bit nebulous. You share, for example, that the Nanit baby monitor told you your son was “sleeping more efficiently than 96% of babies, a solid A.”

I’m skeptical of this idea that a piece of consumer technology will really solve a serious problem families or children have. And if it does solve that problem, it only solves it for people who can afford it, which is reprehensible on some level. These products might create a positive difference for how long your baby is sleeping or how easy the diaper is to put on or whatever, but they are Band-Aids on a larger problem. I often found when I was testing out some of these products that the data [provided] was completely useless. My friend who uses the Nanit texted me the other day because she had found a new feature on its camera that showed you a heat map of where your baby had slept in the crib the night before. There is no use for that information, but when you see the heat map, you can try to interpret it to get some useless clues to your baby’s personality. It’s like a BuzzFeed quiz for your baby, where you can say, “Oh, he’s such, like, a right-side king,” or “He’s a down-the-middle guy,” or whatever.

“[Companies are] marketing a cure for the parents’ anxiety, but the product itself is attached to the body of a newborn child.”

These products encourage you to see your child themselves as an extension of the technology; Karp even talks about there being an on switch and an off switch in your baby for soothing. So if you do the “right” set of movements to activate the right switch, you can make the baby acquire some desirable trait, which I think is just an extension of this idea that your child can be under your complete control.

… which is very much the fantasy when you’re a parent.

These devices are often marketed as quasi-medical devices. There’s a converging of consumer and medical categories in baby consumer tech, where the products are marketed as useful to any potential baby, including one who has a serious medical diagnosis or one who is completely healthy. These companies still want you to put a pulse oximeter on a healthy baby, just in case. They’re marketing a cure for the parents’ anxiety, but the product itself is attached to the body of a newborn child.

After spending so much time in hospital settings with my child hooked up to monitors, I was really excited to end that. So I’m interested in this opposite reaction, where there’s this urge to extend that experience, to take personal control of something that feels medical.

Even though I would search out any medical treatment that would help keep my kids healthy, childhood medical experiences can cause a lot of confusion and trauma for kids and their families, even when the results are positive. When you take that medical experience and turn it into something that’s very sleek and fits in your color scheme and is totally under your control, I think it can feel like you are seizing authority over that scary space.

Another thing you write about is how images define idealized versions of pregnancy and motherhood.

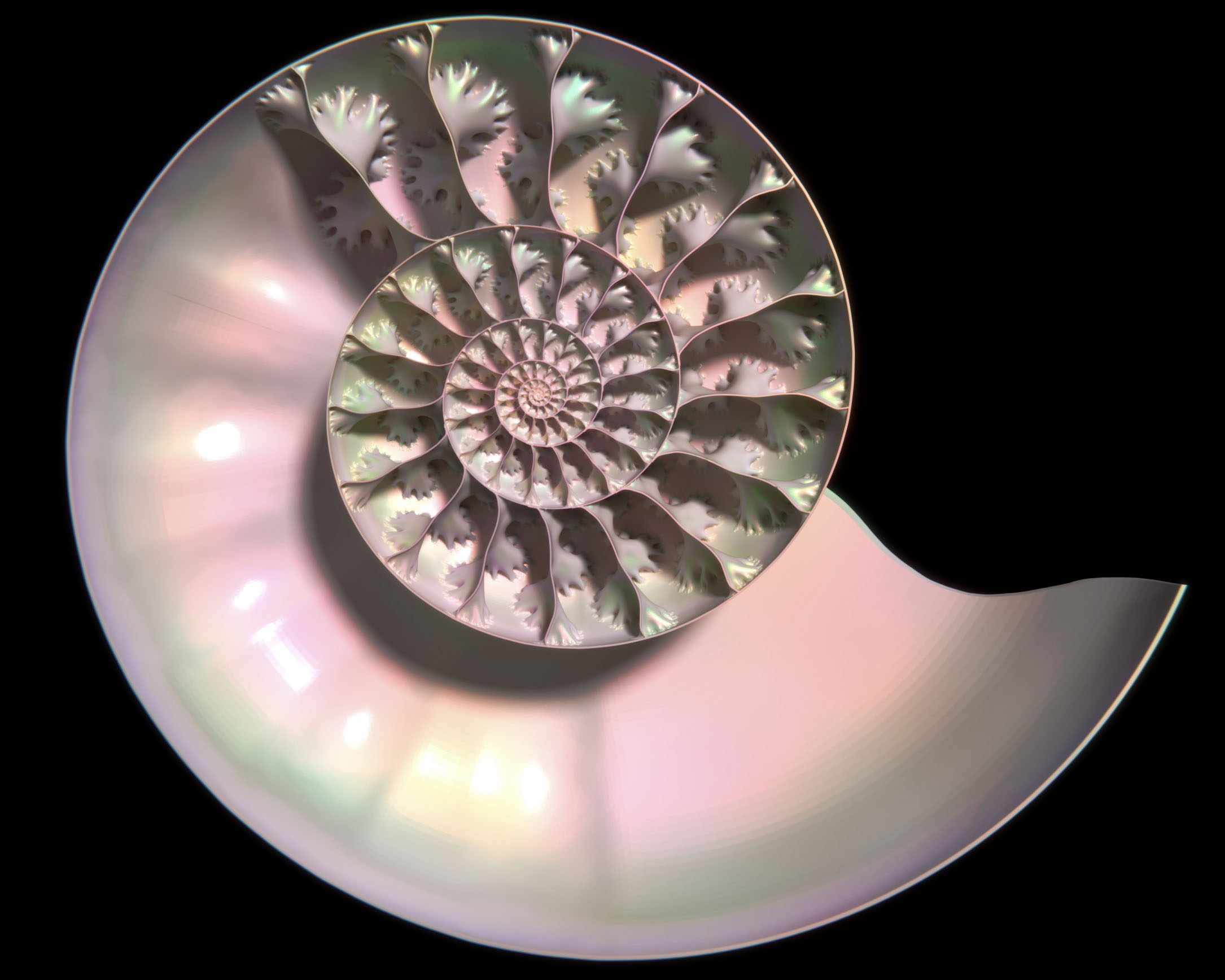

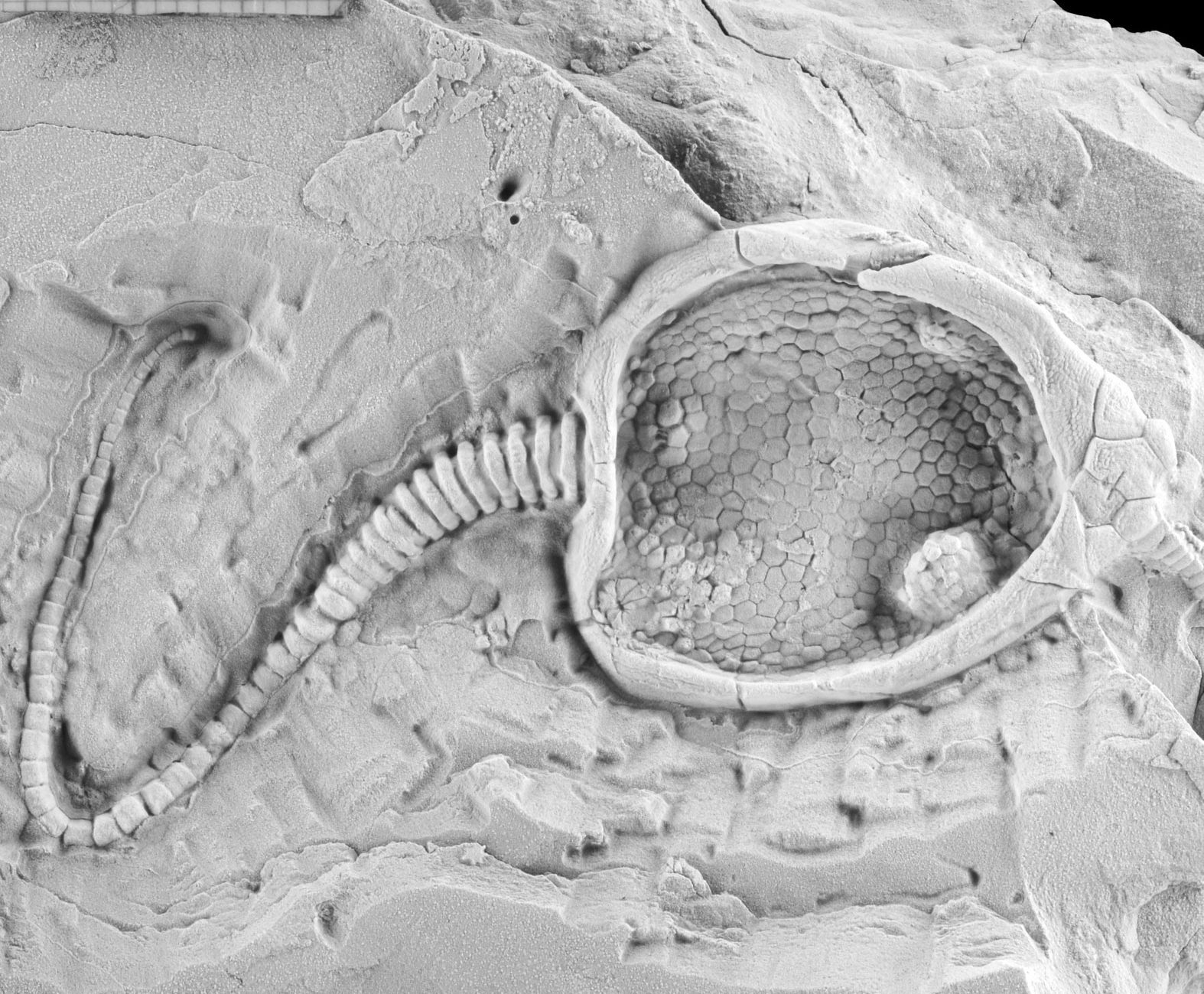

I became interested in a famous photograph that a Swedish photographer named Lennart Nilsson took in the 1960s that was published on the cover of Life magazine. It’s an image of a 20-week-old fetus, and it’s advertised as the world’s first glimpse of life inside the womb. I bought a copy of the issue off eBay and opened the issue to find a little editor’s note saying that the cover fetus was actually a fetus that had been removed from its mother’s body through surgery. It wasn’t a picture of life—it was a picture of an abortion.

I was interested in how Nilsson staged this fetal body to make it look celestial, like it was floating in space, and I recognized a lot of the elements of his work being incorporated in the tech products that I was using, like the CGI fetus generated by my pregnancy app, Flo.

You also write about the images being provided at nonmedical sonogram clinics.

I was trying to google the address of a medical imaging center during my pregnancy when I came across a commercial sonogram clinic. There are hundreds of them around the country, with cutesy names like “Cherished Memories” and “You Kiss We Tell.”

In the book I explore how technologies like ultrasound are used as essentially narrative devices, shaping the way that people think about their bodies and their pregnancies. Ultrasound is odd because it’s a medical technology that’s used to diagnose dangerous and scary conditions, but prospective parents are encouraged to view it as a kind of entertainment service while it’s happening. These commercial sonogram clinics interest me because they promise to completely banish the medical associations of the technology and elevate it into a pure consumer experience.

You write about “natural” childbirth, which, on the face of it, would seem counter to the digital age. As you note, the movement has always been about storytelling, and the story that it’s telling is really about pain.

When I was pregnant, I became really fascinated with people who discuss freebirth online, which is a practice on the very extreme end of “natural” childbirth rituals—where people give birth at home unassisted, with no obstetrician, midwife, or doula present. Sometimes they also refuse ultrasounds, vaccinations, or all prenatal care. I was interested in how this refusal of medical technology was being technologically promoted, through podcasts, YouTube videos, and Facebook groups.

It struck me that a lot of the freebirth influencers I saw were interested in exerting supreme control over their pregnancies and children, leaving nothing under the power of medical experts or government regulators. And they were also interested in controlling the narratives of their births—making sure that the moment their children came into the world was staged with compelling imagery that centered them as the protagonist of the event. Video evidence of the most extreme examples—like the woman who freebirthed into the ocean—could go viral and launch the freebirther’s personal brand as a digital wellness guru in her own right.

The phrase “natural childbirth” was coined by a British doctor, Grantly Dick-Read, in the 1920s. There’s a very funny section in his book for prospective mothers where he complains that women keep telling each other that childbirth hurts, and he claimed that the very idea that childbirth hurts was what created the pain, because birthing women were acting too tense. Dick-Read, like many of his contemporaries, had a racist theory that women he called “primitive” experienced no pain in childbirth because they hadn’t been exposed to white middle-class education and technologies. When I read his work, I was fascinated by the fact that he also described birth as a kind of performance, even back then. He claimed that undisturbed childbirths were totally painless, and he coached women through labor in an attempt to achieve them. Painless childbirth was pitched as a reward for reaching this peak state of natural femininity.

He was really into eugenics, by the way! I see a lot of him in the current presentation of “natural” childbirth online—[proponents] are still invested in a kind of denial, or suppression, of a woman’s actual experience in the pursuit of some unattainable ideal. Recently, I saw one Instagram post from a woman who claimed to have had a supernaturally pain-free childbirth, and she looks so pained and miserable in the photos, it’s absurd.

I wanted to ask you about Clue and Flo, two very different period-tracking apps. Their contrasting origin stories are striking.

I downloaded Flo as my period-tracking app many years ago for one reason: It was the first app that came up when I searched in the app store. Later, when I looked into its origins, I found that Flo was created by two brothers, cisgender men who do not menstruate, and that it had quickly outperformed and outearned an existing period-tracking app, Clue, which was created by a woman, Ida Tin, a few years earlier.

The elements that make an app profitable and successful are not the same as the ones that users may actually want or need. My experience with Flo, especially after I became pregnant, was that it seemed designed to get me to open the app as frequently as possible, even if it didn’t have any new information to provide me about my pregnancy. Flo pitches itself as a kind of artificial nurse, even though it can’t actually examine you or your baby, but this kind of digital substitute has also become increasingly powerful as inequities in maternity care widen and decent care becomes less accessible.

“Doctors and nurses test pregnant women for drugs without their explicit consent or tip off authorities to pregnant people they suspect of mishandling their pregnancies in some way.”

One of the features of Flo I spent a lot of time with was its “Secret Chats” area, where anonymous users come together to go off about pregnancy. It was actually really fun, and it kept me coming back to Flo again and again, especially when I wasn’t discussing my pregnancy with people in real life. But it was also the place where I learned that digital connections are not nearly as helpful as physical connections; you can’t come over and help the anonymous secret chat friend soothe her baby.

I’d asked Ida Tin if she considered adding a social or chat element to Clue, and she told me that she decided against it because it’s impossible to stem the misinformation that surfaces in a space like that.

You write that Flo “made it seem like I was making the empowered choice by surveilling myself.”

After Roe was overturned, many women publicly opted out of that sort of surveillance by deleting their period-tracking apps. But you mention that it’s not just the apps that are sharing information. When I spoke to attorneys who defend women in pregnancy criminalization cases, I found that they had not yet seen a case in which the government actually relied on data from those apps. In some cases, they have relied on users’ Google searches and Facebook messages, but far and away the central surveillance source that governments use is the medical system itself.

Doctors and nurses test pregnant women for drugs without their explicit consent or tip off authorities to pregnant people they suspect of mishandling their pregnancies in some way. I’m interested in the fact that media coverage has focused so much on the potential danger of period apps and less on the real, established threat. I think it’s because it provides a deceptively simple solution: Just delete your period app to protect yourself. It’s much harder to dismantle the surveillance systems that are actually in place. You can’t just delete your doctor.

This interview, which was conducted by phone and email, has been condensed and edited.