Google was recently granted a patent on ranking web pages, which may offer insights into how AI Overviews ranks content. The patent describes a method for ranking pages based on what a user might be interested in next.

Contextual Estimation Of Link Information Gain

The name of the patent is Contextual Estimation Of Link Information Gain, it was filed in 2018 and granted in June 2024. It’s about calculating a ranking score called Information Gain that is used to rank a second set of web pages that are likely to be of interest to a user as a slightly different follow-up topic related to a previous question.

The patent starts with general descriptions then adds layers of specifics over the course of paragraphs. An analogy can be that it’s like a pizza. It starts out as a mozzarella pizza, then they add mushrooms, so now it’s a mushroom pizza. Then they add onions, so now it’s a mushroom and onion pizza. There are layers of specifics that build up to the entire context.

So if you read just one section of it, it’s easy to say, “It’s clearly a mushroom pizza” and be completely mistaken about what it really is.

There are layers of context but what it’s building up to is:

- Ranking a web page that is relevant for what a user might be interested in next.

- The context of the invention is an automated assistant or chatbot

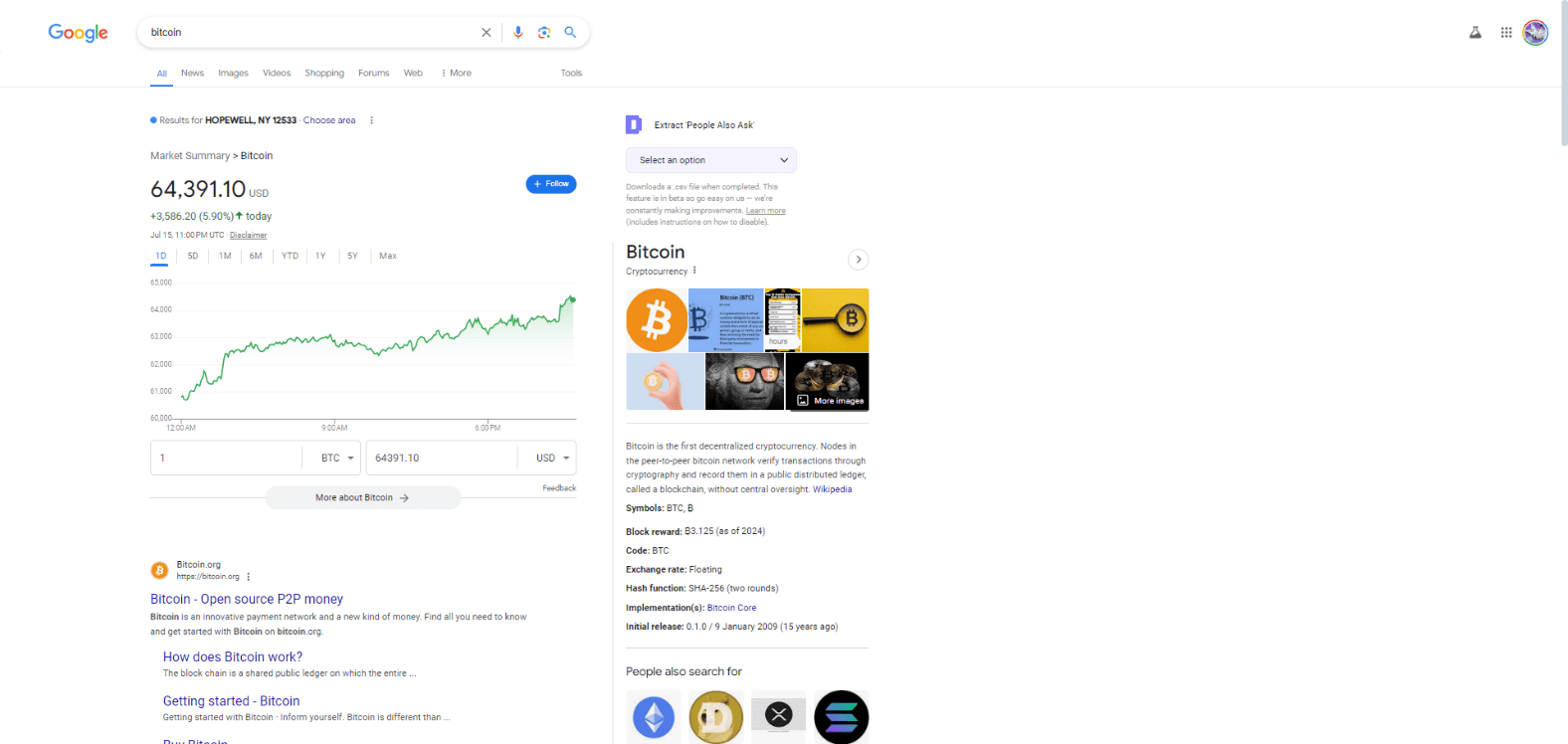

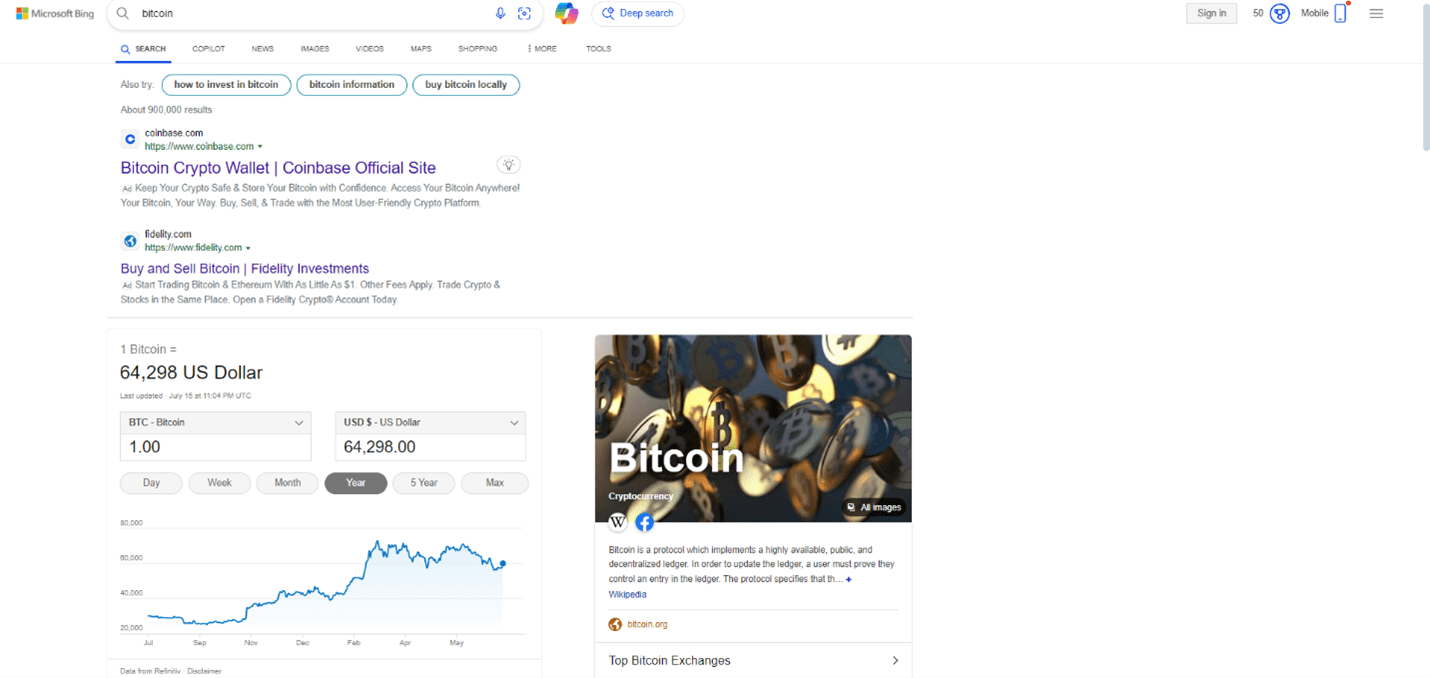

- A search engine plays a role in a way that seems similar to Google’s AI Overviews

Information Gain And SEO: What’s Really Going On?

A couple of months ago I read a comment on social media asserting that “Information Gain” was a significant factor in a recent Google core algorithm update. That mention surprised me because I’d never heard of information gain before. I asked some SEO friends about it and they’d never heard of it either.

What the person on social media had asserted was something like Google was using an “Information Gain” score to boost the ranking of web pages that had more information than other web pages. So the idea was that it was important to create pages that have more information than other pages, something along those lines.

So I read the patent and discovered that “Information Gain” is not about ranking pages with more information than other pages. It’s really about something that is more profound for SEO because it might help to understand one dimension of how AI Overviews might rank web pages.

TL/DR Of The Information Gain Patent

What the information gain patent is really about is even more interesting because it may give an indication of how AI Overviews (AIO) ranks web pages that a user might be interested next. It’s sort of like introducing personalization by anticipating what a user will be interested in next.

The patent describes a scenario where a user makes a search query and the automated assistant or chatbot provides an answer that’s relevant to the question. The information gain scoring system works in the background to rank a second set of web pages that are relevant to a what the user might be interested in next. It’s a new dimension in how web pages are ranked.

The Patent’s Emphasis on Automated Assistants

There are multiple versions of the Information Gain patent dating from 2018 to 2024. The first version is similar to the last version with the most significant difference being the addition of chatbots as a context for where the information gain invention is used.

The patent uses the phrase “automated assistant” 69 times and uses the phrase “search engine” only 25 times. Like with AI Overviews, search engines do play a role in this patent but it’s generally in the context of automated assistants.

As will become evident, there is nothing to suggest that a web page containing more information than the competition is likelier to be ranked higher in the organic search results. That’s not what this patent talks about.

General Description Of Context

All versions of the patent describe the presentation of search results within the context of an automated assistant and natural language question answering. The patent starts with a general description and progressively becomes more specific. This is a feature of patents in that they apply for protection for the widest contexts in which the invention can be used and become progressively specific.

The entire first section (the Abstract) doesn’t even mention web pages or links. It’s just about the information gain score within a very general context:

“An information gain score for a given document is indicative of additional information that is included in the document beyond information contained in documents that were previously viewed by the user.”

That is a nutshell description of the patent, with the key insight being that the information gain scoring happens on pages after the user has seen the first search results.

More Specific Context: Automated Assistants

The second paragraph in the section titled “Background” is slightly more specific and adds an additional layer of context for the invention because it mentions links. Specifically, it’s about a user that makes a search query and receives links to search results – no information gain score calculated yet.

The Background section says:

“For example, a user may submit a search request and be provided with a set of documents and/or links to documents that are responsive to the submitted search request.”

The next part builds on top of a user having made a search query:

“Also, for example, a user may be provided with a document based on identified interests of the user, previously viewed documents of the user, and/or other criteria that may be utilized to identify and provide a document of interest. Information from the documents may be provided via, for example, an automated assistant and/or as results to a search engine. Further, information from the documents may be provided to the user in response to a search request and/or may be automatically served to the user based on continued searching after the user has ended a search session.”

That last sentence is poorly worded.

Here’s the original sentence:

“Further, information from the documents may be provided to the user in response to a search request and/or may be automatically served to the user based on continued searching after the user has ended a search session.”

Here’s how it makes more sense:

“Further, information from the documents may be provided to the user… based on continued searching after the user has ended a search session.”

The information provided to the user is “in response to a search request and/or may be automatically served to the user”

It’s a little clearer if you put parentheses around it:

Further, information from the documents may be provided to the user (in response to a search request and/or may be automatically served to the user) based on continued searching after the user has ended a search session.

Takeaways:

- The patent describes identifying documents that are relevant to the “interests of the user” based on “previously viewed documents” “and/or other criteria.”

- It sets a general context of an automated assistant “and/or” a search engine

- Information from the documents that are based on “previously viewed documents” “and/or other criteria” may be shown after the user continues searching.

More Specific Context: Chatbot

The patent next adds an additional layer of context and specificity by mentioning how chatbots can “extract” an answer from a web page (“document”) and show that as an answer. This is about showing a summary that contains the answer, kind of like featured snippets, but within the context of a chatbot.

The patent explains:

“In some cases, a subset of information may be extracted from the document for presentation to the user. For example, when a user engages in a spoken human-to-computer dialog with an automated assistant software process (also referred to as “chatbots,” “interactive personal assistants,” “intelligent personal assistants,” “personal voice assistants,” “conversational agents,” “virtual assistants,” etc.), the automated assistant may perform various types of processing to extract salient information from a document, so that the automated assistant can present the information in an abbreviated form.

As another example, some search engines will provide summary information from one or more responsive and/or relevant documents, in addition to or instead of links to responsive and/or relevant documents, in response to a user’s search query.”

The last sentence sounds like it’s describing something that’s like a featured snippet or like AI Overviews where it provides a summary. The sentence is very general and ambiguous because it uses “and/or” and “in addition to or instead of” and isn’t as specific as the preceding sentences. It’s an example of a patent being general for legal reasons.

Ranking The Next Set Of Search Results

The next section is called the Summary and it goes into more details about how the Information Gain score represents how likely the user will be interested in the next set of documents. It’s not about ranking search results, it’s about ranking the next set of search results (based on a related topic).

It states:

“An information gain score for a given document is indicative of additional information that is included in the given document beyond information contained in other documents that were already presented to the user.”

Ranking Based On Topic Of Web Pages

It then talks about presenting the web page in a browser, audibly reading the relevant part of the document or audibly/visually presenting a summary of the document (“audibly/visually presenting salient information extracted from the document to the user, etc.”)

But the part that’s really interesting is when it next explains using a topic of the web page as a representation of the the content, which is used to calculate the information gain score.

It describes many different ways of extracting the representation of what the page is about. But what’s important is that it’s describes calculating the Information Gain score based on a representation of what the content is about, like the topic.

“In some implementations, information gain scores may be determined for one or more documents by applying data indicative of the documents, such as their entire contents, salient extracted information, a semantic representation (e.g., an embedding, a feature vector, a bag-of-words representation, a histogram generated from words/phrases in the document, etc.) across a machine learning model to generate an information gain score.”

The patent goes on to describe ranking a first set of documents and using the Information Gain scores to rank additional sets of documents that anticipate follow up questions or a progression within a dialog of what the user is interested in.

The automated assistant can in some implementations query a search engine and then apply the Information Gain rankings to the multiple sets of search results (that are relevant to related search queries).

There are multiple variations of doing the same thing but in general terms this is what it describes:

“Based on the information gain scores, information contained in one or more of the new documents may be selectively provided to the user in a manner that reflects the likely information gain that can be attained by the user if the user were to be presented information from the selected documents.”

What All Versions Of The Patent Have In Common

All versions of the patent share general similarities over which more specifics are layered in over time (like adding onions to a mushroom pizza). The following are the baseline of what all the versions have in common.

Application Of Information Gain Score

All versions of the patent describe applying the information gain score to a second set of documents that have additional information beyond the first set of documents. Obviously, there is no criteria or information to guess what the user is going search for when they start a search session. So information gain scores are not applied to the first search results.

Examples of passages that are the same for all versions:

- A second set of documents is identified that is also related to the topic of the first set of documents but that have not yet been viewed by the user.

- For each new document in the second set of documents, an information gain score is determined that is indicative of, for the new document, whether the new document includes information that was not contained in the documents of the first set of documents…

Automated Assistants

All four versions of the patent refer to automated assistants that show search results in response to natural language queries.

The 2018 and 2023 versions of the patent both mention search engines 25 times. The 2o18 version mentions “automated assistant” 74 times and the latest version mentions it 69 times.

They all make references to “conversational agents,” “interactive personal assistants,” “intelligent personal assistants,” “personal voice assistants,” and “virtual assistants.”

It’s clear that the emphasis of the patent is on automated assistants, not the organic search results.

Dialog Turns

Note: In everyday language we use the word dialogue. In computing they the spell it dialog.

All versions of the patents refer to a way of interacting with the system in the form of a dialog, specifically a dialog turn. A dialog turn is the back and forth that happens when a user asks a question using natural language, receives an answer and then asks a follow up question or another question altogether. This can be natural language in text, text to speech (TTS), or audible.

The main aspect the patents have in common is the back and forth in what is called a “dialog turn.” All versions of the patent have this as a context.

Here’s an example of how the dialog turn works:

“Automated assistant client 106 and remote automated assistant 115 can process natural language input of a user and provide responses in the form of a dialog that includes one or more dialog turns. A dialog turn may include, for instance, user-provided natural language input and a response to natural language input by the automated assistant.

Thus, a dialog between the user and the automated assistant can be generated that allows the user to interact with the automated assistant …in a conversational manner.”

Problems That Information Gain Scores Solve

The main feature of the patent is to improve the user experience by understanding the additional value that a new document provides compared to documents that a user has already seen. This additional value is what is meant by the phrase Information Gain.

There are multiple ways that information gain is useful and one of the ways that all versions of the patent describes is in the context of an audio response and how a long-winded audio response is not good, including in a TTS (text to speech) context).

The patent explains the problem of a long-winded response:

“…and so the user may wait for substantially all of the response to be output before proceeding. In comparison with reading, the user is able to receive the audio information passively, however, the time taken to output is longer and there is a reduced ability to scan or scroll/skip through the information.”

The patent then explains how information gain can speed up answers by eliminating redundant (repetitive) answers or if the answer isn’t enough and forces the user into another dialog turn.

This part of the patent refers to the information density of a section in a web page, a section that answers the question with the least amount of words. Information density is about how “accurate,” “concise,” and “relevant”‘ the answer is for relevance and avoiding repetitiveness. Information density is important for audio/spoken answers.

This is what the patent says:

“As such, it is important in the context of an audio output that the output information is relevant, accurate and concise, in order to avoid an unnecessarily long output, a redundant output, or an extra dialog turn.

The information density of the output information becomes particularly important in improving the efficiency of a dialog session. Techniques described herein address these issues by reducing and/or eliminating presentation of information a user has already been provided, including in the audio human-to-computer dialog context.”

The idea of “information density” is important in a general sense because it communicates better for users but it’s probably extra important in the context of being shown in chatbot search results, whether it’s spoken or not. Google AI Overviews shows snippets from a web page but maybe more importantly, communicating in a concise manner is the best way to be on topic and make it easy for a search engine to understand content.

Search Results Interface

All versions of the Information Gain patent are clear that the invention is not in the context of organic search results. It’s explicitly within the context of ranking web pages within a natural language interface of an automated assistant and an AI chatbot.

However, there is a part of the patent that describes a way of showing users with the second set of results within a “search results interface.” The scenario is that the user sees an answer and then is interested in a related topic. The second set of ranked web pages are shown in a “search results interface.”

The patent explains:

“In some implementations, one or more of the new documents of the second set may be presented in a manner that is selected based on the information gain stores. For example, one or more of the new documents can be rendered as part of a search results interface that is presented to the user in response to a query that includes the topic of the documents, such as references to one or more documents. In some implementations, these search results may be ranked at least in part based on their respective information gain scores.”

…The user can then select one of the references and information contained in the particular document can be presented to the user. Subsequently, the user may return to the search results and the references to the document may again be provided to the user but updated based on new information gain scores for the documents that are referenced.

In some implementations, the references may be reranked and/or one or more documents may be excluded (or significantly demoted) from the search results based on the new information gain scores that were determined based on the document that was already viewed by the user.”

What is a search results interface? I think it’s just an interface that shows search results.

Let’s pause here to underline that it should be clear at this point that the patent is not about ranking web pages that are comprehensive about a topic. The overall context of the invention is showing documents within an automated assistant.

A search results interface is just an interface, it’s never described as being organic search results, it’s just an interface.

There’s more that is the same across all versions of the patent but the above are the important general outlines and context of it.

Claims Of The Patent

The claims section is where the scope of the actual invention is described and for which they are seeking legal protection over. It is mainly focused on the invention and less so on the context. Thus, there is no mention of a search engines, automated assistants, audible responses, or TTS (text to speech) within the Claims section. What remains is the context of search results interface which presumably covers all of the contexts.

Context: First Set Of Documents

It starts out by outlining the context of the invention. This context is receiving a query, identifying the topic, and ranking a first group of relevant web pages (documents) and selecting at least one of them as being relevant and either showing the document or communicating the information from the document (like a summary).

“1. A method implemented using one or more processors, comprising: receiving a query from a user, wherein the query includes a topic; identifying a first set of documents that are responsive to the query, wherein the documents of the set of documents are ranked, and wherein a ranking of a given document of the first set of documents is indicative of relevancy of information included in the given document to the topic; selecting, based on the rankings and from the documents of the first set of documents, a most relevant document providing at least a portion of the information from the most relevant document to the user;”

Context: Second Set Of Documents

Then what immediately follows is the part about ranking a second set of documents that contain additional information. This second set of documents is ranked using the information gain scores to show more information after showing a relevant document from the first group.

This is how it explains it:

“…in response to providing the most relevant document to the user, receiving a request from the user for additional information related to the topic; identifying a second set of documents, wherein the second set of documents includes at one or more of the documents of the first set of documents and does not include the most relevant document; determining, for each document of the second set, an information gain score, wherein the information gain score for a respective document of the second set is based on a quantity of new information included in the respective document of the second set that differs from information included in the most relevant document; ranking the second set of documents based on the information gain scores; and causing at least a portion of the information from one or more of the documents of the second set of documents to be presented to the user, wherein the information is presented based on the information gain scores.”

Granular Details

The rest of the claims section contains granular details about the concept of Information Gain, which is a ranking of documents based on what the user already has seen and represents a related topic that the user may be interested in. The purpose of these details is to lock them in for legal protection as part of the invention.

Here’s an example:

The method of claim 1, wherein identifying the first set comprises:

causing to be rendered, as part of a search results interface that is presented to the user in response to a previous query that includes the topic, references to one or more documents of the first set;

receiving user input that that indicates selection of one of the references to a particular document of the first set from the search results interface, wherein at least part of the particular document is provided to the user in response to the selection;

To make an analogy, it’s describing how to make the pizza dough, clean and cut the mushrooms, etc. It’s not important for our purposes to understand it as much as the general view of what the patent is about.

Information Gain Patent

An opinion was shared on social media that this patent has something to do with ranking web pages in the organic search results, I saw it, read the patent and discovered that’s not how the patent works. It’s a good patent and it’s important to correctly understand it. I analyzed multiple versions of the patent to see what they had in common and what was different.

A careful reading of the patent shows that it is clearly focused on anticipating what the user may want to see based on what they have already seen. To accomplish this the patent describes the use of an Information Gain score for ranking web pages that are on topics that are related to the first search query but not specifically relevant to that first query.

The context of the invention is generally automated assistants, including chatbots. A search engine could be used as part of finding relevant documents but the context is not solely an organic search engine.

This patent could be applicable to the context of AI Overviews. I would not limit the context to AI Overviews as there are additional contexts such as spoken language in which Information Gain scoring could apply. Could it apply in additional contexts like Featured Snippets? The patent itself is not explicit about that.

Read the latest version of Information Gain patent:

Contextual estimation of link information gain

Featured Image by Shutterstock/Khosro