It’s officially the end of organic search as we know it. A recent survey reveals that 83% of consumers believe AI-powered search tools are more efficient than traditional search engines.

The days of simple search are long gone, and a profound transformation continues to sweep the search engine results pages (SERPs). The rise of AI-powered answer engines, from ChatGPT to Perplexity to Google’s AI Overviews, is rewriting the rules of online visibility.

Instead of returning traditional blue links or images, AI systems are returning immediate results. For marketing leaders, the question is no longer “How do we rank number one?” but rather “How do we become the top answer?”

This shift has eliminated the distance between the search and the solution. No longer do customers need to click through to find the information they’re seeking. And while zero-click searches are more prevalent and old metrics like keyword rankings are fading fast, it also creates a massive opportunity for chief marketing officers to redefine SEO as a strategic growth function.

Yes, content remains king, but it must be rooted in a foundation that fuels authority, brand trust, and authenticity to serve the systems that are shaping what appears when a search is conducted. This isn’t just a new channel; it’s a new way of creating, structuring, and validating content

In this post, we’ll dissect how to redesign content workflows for generative engines to ensure your content reigns supreme in an AI-first era.

What Generative Engines Changed And Why “Traditional SEO” Won’t Recover

When users ask generative search engines a question, they aren’t presented with a list of websites to click through to learn more; instead, they’re given a quick, synthesized answer. The source of the answer is cited, allowing users to click to learn more if they so choose to. These citations are the new “rankings” and most likely to be clicked on.

In fact, research shows 60% of consumers click through at least sometimes after seeing an AI-generated overview in Google Search. A separate study found that 91% of frequent AI users turn to popular large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT for their searching needs.

While keyword optimization still holds importance in content marketing, generative engines are favoring expertise, brand authority, and structured data. For CMOs, the old metrics no longer necessarily equate to success. Visibility and impressions are no longer tied to website traffic, and success is now contingent upon citations, mentions, and verifiable authority signals.

The AI era signals a serious identity shift, one in which traditional SEO collides with AI-driven search. SEO can no longer be a mechanical, straightforward checklist that sits under demand generation. It must integrate with a broader strategy to manage brand knowledge, ensuring that when AI pulls data to form an answer, your content is what they trust most out of all the options out there.

In this new search era, improving visibility can be measured in three diverse ways:

- Appearing in results or answers.

- Being seen as a thought leader in your space by being cited or trusted as a credible source.

- Driving influence, affinity, or conversions from your digital presence.

Traditional SEO is now only one piece of the content visibility puzzle. Generative SEO demands fluency across all three.

The CMO’s New Dilemma: AI As Both Channel And Competitor

Consumers have questions. Generative engines have the answers. With over half (56%) of consumers trusting the use of Gen AI as an education resource, generative engines are now mediators between your brand and your customers. They can influence purchases or sway customers toward your competition, depending on whether your content earns their hard-earned trust.

For example, if a customer asks, “What’s the best CRM for enterprise brands?” and an AI engine suggests HubSpot’s content over your brand, the damage isn’t just a lost click but a missed opportunity to garner interest and trust with that motivated searcher. The hard truth is the Gen AI model didn’t see your content as relevant or reliable enough to deliver in its answer.

Generative engines are trained on content that already exists, meaning your competitors’ content, user reviews, forum discussions, and your own material are all fair game. That means AI is both a discovery channel and competitor for audience attention. This duality must be recognized by CMOs to invest in structuring, amplifying, and revamping content workflows to match Gen AI’s expectations. The goal isn’t to chase algorithms; it’s to shape the content in a meaningful way to ensure those algorithms trust and view your content as the single source of truth.

Think of it this way: Traditional SEO practices taught you to optimize content for crawlers. With Generative SEO, you’re optimizing for the model’s memory.

How To Redesign SEO Content Workflows For The Generative Era

To win citations and influence AI-generated answers, it’s time to throw out your old playbooks and overhaul previous workflows. It may be time to ditch how you used to plan content and how performance was measured. Out with the old and in with the new (and more successful).

From Keyword Targeting To Knowledge Modeling

Generative models go beyond understanding just keywords. They understand entities and relationships, too. To show up in coveted AI answers and to be the top choice, your content must reflect structured, interconnected knowledge.

Start by building a brand knowledge graph that maps people, products, and topics that define your expertise. Schema markup is also a must to show how these entities connect. Additionally, every piece of content you produce should reinforce your position within that network.

Long-tail keywords may be easier to target and rank for in traditional SEO; however, optimizing for AI search requires a shift in content workflows, one that targets “entity clusters” instead. Here’s what this might look like in practice: A software company wouldn’t only optimize content around the focus keyword phrase “best CRM integrations.” The writer should also define its relationship to the concept of “CRM,” “workflow automation,” “customer data,” and other related phrases.

From Content Volume To Verifiable Authority

It was once thought that the more content, the better. This is not the case with SEO today as AI systems prefer and prioritize content that’s well-sourced, attributable, and authoritative. Content velocity is no longer the end game, but rather producing stronger, more evidence-backed pieces.

Marketing leaders should create an AI-readiness checklist for their content marketing team to ensure every piece of content is optimized for generative engines. Every article should include author credentials (job title, advanced degrees, and certifications), clear citations (where the statistics or research came from), and verifiable claims.

Create an AI-readiness checklist for your team. Every article should include author credentials, clear citations, and verifiable claims. Reference independent studies and owned research where possible. AI models cross-validate multiple sources to determine what’s credible and reliable.

In short: Don’t publish faster. Publish smarter.

From Static Publishing To Dynamic Feedback

If one thing is certain, it’s that generative engines are continuing to evolve, similar to traditional search. What ranks well today may change entirely tomorrow. That’s why successful SEO teams are adopting an agile publishing cycle to continue to stay on top of what’s working best. SEO teams are actively and consistently:

- Testing which questions their audience asks in generative engines.

- Tracking whether their content appears in those answers.

- Refreshing content based on what’s being cited, summarized, or ignored.

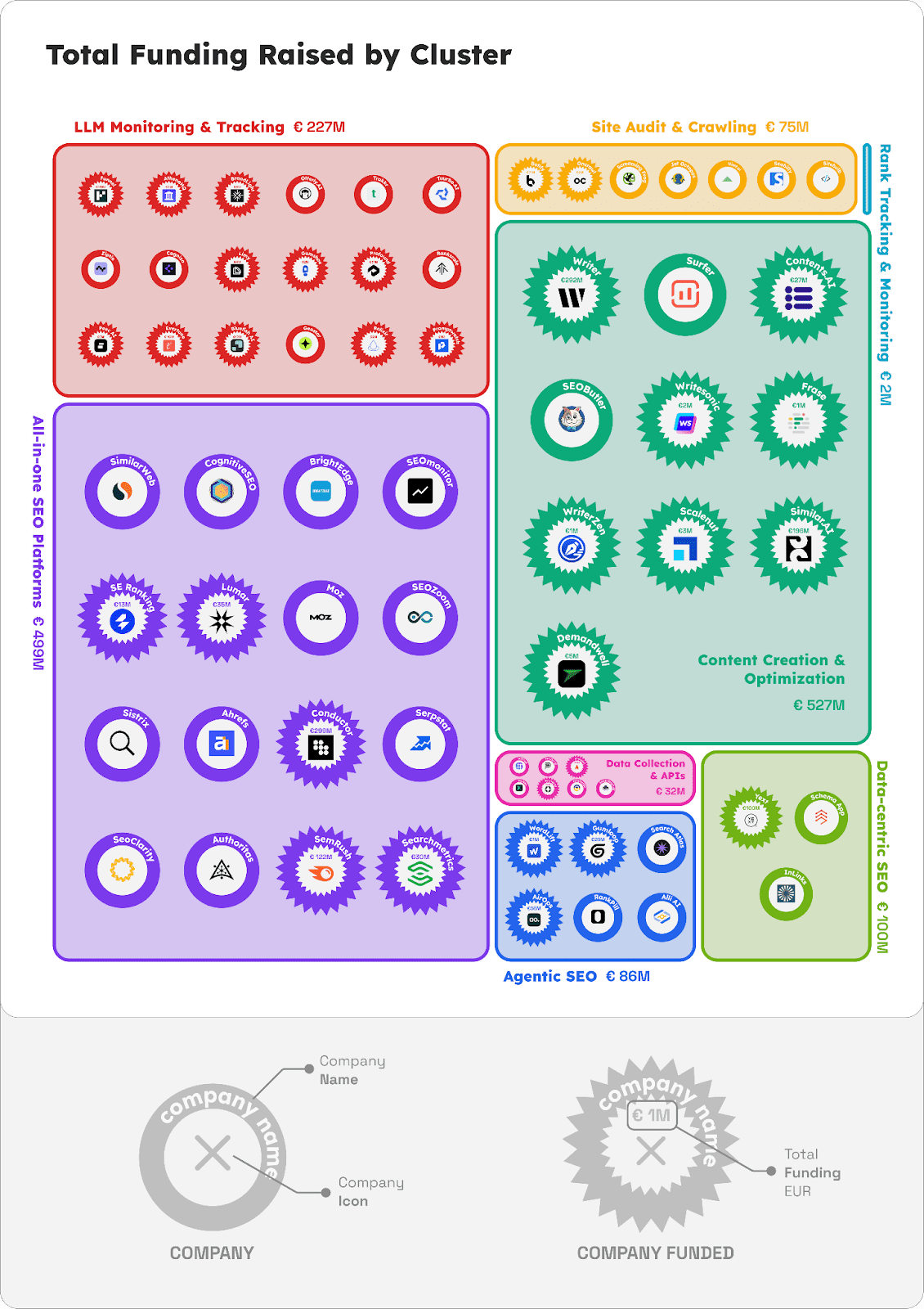

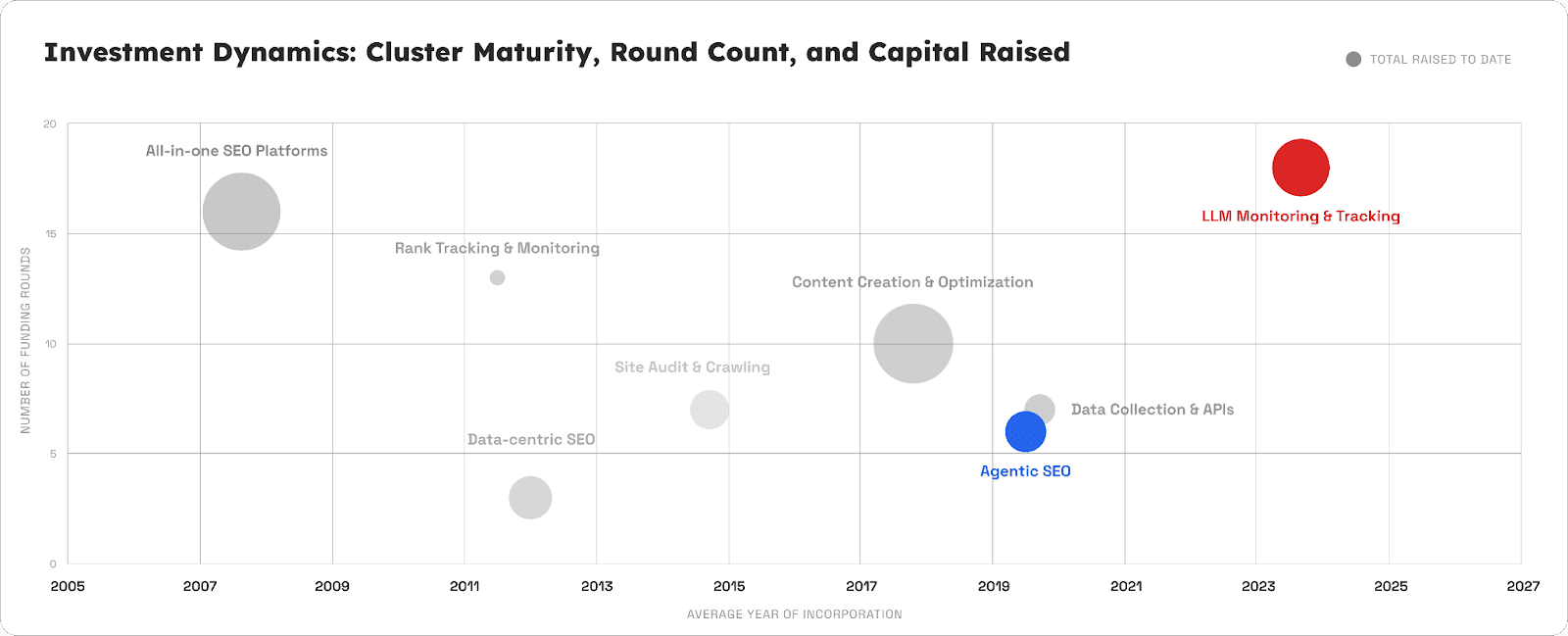

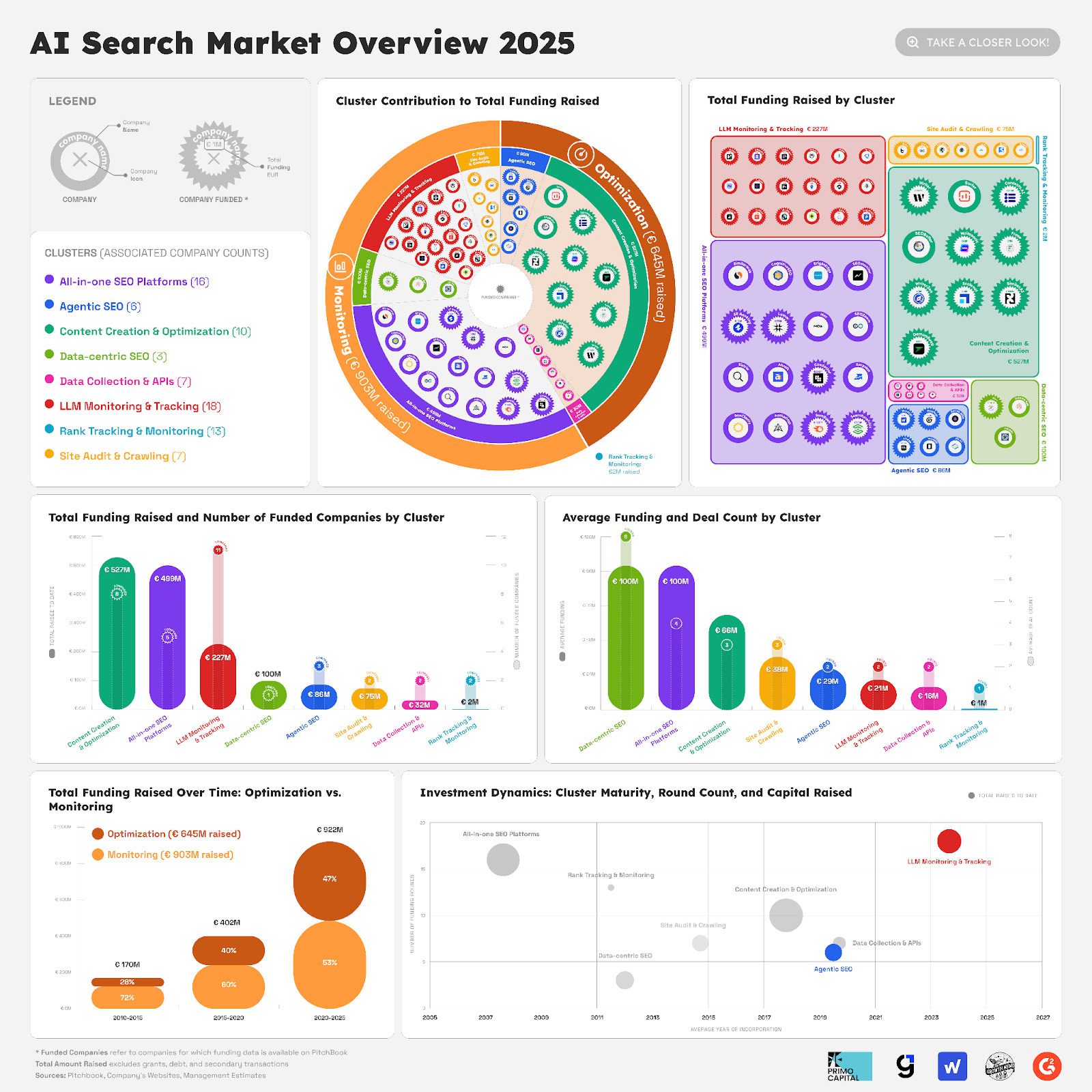

Several tools are emerging to help you track your brand’s presence across, ChatGPT, Perplexity, AI Overviews, and more, including SE Ranking, Peec AI, Profound, and Conductor. If you choose to forego tools, you can also run regular AI audits on your own to see how your brand is represented across engines by following the aforementioned framework. Treat that data like search console metrics and think of it as your new visibility report.

How To Measure SEO Success In An Answer-Driven World

Measuring SEO success across generative engines looks different than how we used to measure traditional SEO. Traffic will always matter, but it’s no longer the sole proof of impact. For CMOs, understanding how to measure marketing’s impact is essential to demonstrate the value your team delivers to the organization’s mission.

Here’s how progressive CMOs are redefining SEO success:

- AI Citations: How often your content is referenced within AI-generated responses.

- Answer Visibility Share: The percentage of relevant queries where your content appears in an AI answer.

- Zero-Click Exposure: Instances where your brand is visible in AI responses, even if users don’t visit your site.

- Answer Referral Traffic: The new “clicks”; visits that originate directly from AI-generated links.

- Semantic Coverage: The breadth of related entities and subtopics your brand consistently appears for.

These metrics move SEO reporting from vanity numbers to visibility intelligence and are a more accurate representation of brand authority in the machine age.

Future-Proof Your SEO For Generative Search

Generative search is just as volatile as traditional search, but volatility is fertile ground for innovation. Instead of resisting it, CMOs should continue to treat SEO as an experimental function; a sandbox for continuously testing new ways to be discovered and trusted. SEO continues to remain a function that isn’t a set it and forget it, but one that must change with time and testing.

CMOs should encourage their team to A/B test content formats, schema implementations, and even phrasing to see what appears in AI generated responses. Cross-pollinate SEO insights with PR, product, and customer experience. When your organization learns how AI represents your brand, it becomes a feedback loop that strengthens everything from messaging to market positioning.

In the near future, the term “organic search” will become something broader to encompass the fast-growing ecosystem of machine-mediated discovery. The brands that succeed won’t just optimize for keywords. They’ll build long-lasting trust.

The Next Evolution Of Search

The notion that AI is killing SEO is false. AI isn’t eliminating SEO but rather redefining what it means today. What used to be a tactical discipline is shifting to become a more strategic approach that requires understanding how your brand exists within digital knowledge systems. It’s straying from what’s comfortable and moving into largely uncharted territory.

The opportunity for marketing leaders is clear: It’s time to move past the known and venture into the somewhat elusive realm of generative answer engines. After all, Forrester predicts AI-powered search will drive 20% of all organic traffic by the end of 2025. At the end of the day, many of the traditional SEO best practices still apply: create content that’s verifiable, well-structured, and context-rich. The main mindset shift lies in how to measure generative engine success, not by rankings but by relevance in conversation.

In the age of AI answers, your brand doesn’t need to just be searchable; it needs to be knowable.

More Resources:

Featured Image: Roman Samborskyi/Shutterstock